Whatever happened to full employment?

- Published

- comments

Full employment used to be a much-cherished political mantra. Why does it seem to have disappeared from public debate?

Today all politicians want to cut unemployment from its present high levels. But once upon a time the goal was full employment - a common political slogan in post-war Britain as society attempted to put behind it the horrors of the Great Depression.

Former US president Bill Clinton subscribed to a modern form of it when he said: "I do not believe we can repair the basic fabric of society until people who are willing to work have work."

But the very idea that the government should be able to create an economy in which everyone is able to get a job might already sound dated to some. This week the UK's unemployment figure rose to 2.57 million, a rate of 8.1%. It is lower than the US (9.1%), Greece (16.7%) and Spain (21.2%). But it is the highest it has been in the UK since 1994, with more than a fifth of those aged 16-24 without a job.

But has there ever been full employment? That depends, like a lot of economics, on one's definition of the term.

"Full employment never meant zero unemployment," says Christopher Pissarides, professor of economics at the London School of Economics.

Instead there is what the free market economist Milton Friedman termed a "natural rate" of unemployment, where nobody stays out of work for long, unemployment fluctuates between 5% and 6% with jobless workers quickly being hired in growth sectors of the economy.

Other economists argue this is too high. William Beveridge, the man who inspired Britain's post-war welfare state, said full employment meant a figure of under 3%.

Before the world became industrialised, nearly everyone outside the rich elite would have had to work to survive, usually in the fields. After industrialisation all that changed. Mechanisation offered people work in the factories but also brought huge spikes in employment and an intensification of economic boom and bust.

Pissarides argues that full employment was a reality in the US in the 1990s under Bill Clinton and from 1997-2007 in Britain, and in modern day China.

Other economists say it's not fair to compare democracies with autocratic societies. Children learn in history lessons about the mass mobilisation of men in Hitler's Germany for armaments production and public works programmes. "Conscripting people over the barrel of the gun in totalitarian societies is not full employment as economists understand the term," says economic historian Tim Leunig.

In 1955 unemployment was very low indeed

So has genuine full employment ever been achieved in the post industrial world? "Of course we've had it," says the economist Lord Skidelsky. "Between 1950 and 1973 unemployment averaged 2% and was always well under one million."

This was the golden age for jobs in Britain. The high point came in July 1955 - shortly after Anthony Eden had taken over from Winston Churchill as prime minister - when unemployment reached a post-war low of 215,800, a mere 1%.

So what happened to full employment? Ian Brinkley, director of think tank the Work Foundation, says the term went out of fashion in the 1970s as unemployment passed one million.

Then in the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher pursued a different approach, which economists characterised as the prioritising of tackling inflation. The concept of full employment was dead, says Brinkley.

Unemployment climbed above the symbolically important three million figure, and stayed relatively high despite economic recovery.

It was the election of Tony Blair in 1997 that saw renewed talk of full employment. "New Labour came in and adopted a modern version of full employment," Brinkley says. Blair and Chancellor Gordon Brown no longer sought a low percentage of unemployment. Instead they changed the definition to boosting the total number of jobs.

Writing in his autobiography, A Journey, Blair claimed that by the time he stepped down there were "over 2.5m more in work". It was a cunning shifting of the goal posts, Brinkley says. With a rising population the party was almost guaranteed to boost the number of jobs in the economy.

Neither did it have to say who was getting the jobs. Campaign groups like Migration Watch argue that the majority of jobs created by Labour went to foreign workers, leaving the proportion of unemployed Britons little changed.

And then there was the issue of misleading figures. In 1998 the total on incapacity benefit was "1.7m and rising", Blair writes in his memoirs. The unemployment statistics "masked the huge rise in numbers on incapacity benefit that had taken place under the Tories and was continuing under us" he conceded.

Now unemployment is rising again there may be some politicians who under their breath admit it is no bad thing. In 1992, Conservative Chancellor Norman Lamont said: "Rising unemployment and the recession have been the price we have had to pay to get inflation down. That is a price well worth paying."

Some argue that it was the policy of the Thatcher government in the 1980s to use rising unemployment as a brake on inflation. The theory is that as people lose their jobs, the pressure for wage rises diminishes. But Conservative MP John Redwood, chairman of the party's policy review group on economic competitiveness, disputes that this was Thatcher's aim.

She was pursuing a "sensible" approach to control inflation so that the economy could recover and unemployment would fall in the longer term, he argues.

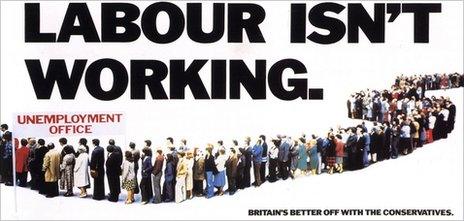

This notable poster was used in the 1979 UK general election campaign

Pissarides says the problem with Thatcher was that rising unemployment was not a temporary situation but continued for many years.

But he agrees with the theory that some unemployment is better for an economy than none. "It is better to have 1% or 2% unemployment than zero because the smaller rates will give rise to labour shortages and cause inflation."

Others disagree. The late James Tobin, whose theories are said to be guiding President Obama's stimulus programme, believed that there was no such thing as an optimum level of unemployment.

"I did a paper where I analysed the optimal unemployment rate," the economist Joseph Stiglitz was quoted as saying in a Bloomberg article. "Tobin went livid over the idea. To him the optimal unemployment rate was zero."

Redwood agrees with Tobin's idea that full employment means getting everyone a job. "I'm not sure it's gone out of fashion. All three political parties have a high level aim of full employment."

In the 1930s, unemployment soared

The problem is not the desire to bring in full employment but delivering it. Labour stopped talking about it because they had difficulty in achieving it, Redwood argues.

And David Cameron's government faces both the financial crisis and an "enormous economic challenge from the East". Redwood is pessimistic about whether it can be delivered in the near future. "Recently it's proved beyond the ability of most Western governments."

The historian David Kynaston says the issue is as much psychological as economic. He argues that there was a "psychic shift" towards accepting unemployment in the 1980s.

Up to the election of Margaret Thatcher, it was believed that any government that created mass unemployment would fall at the next election. Yet in 1983, despite taking unemployment to over three million, the Conservatives won with an increased majority.

The view of unemployment had changed forever. "As long as most people were in work it didn't matter if rather a lot of other people, albeit a minority, were not. So unemployment lost its profile as an issue."

And with unemployment once again nearing the three million mark, Cameron and Chancellor George Osborne will be focused on turning the tide of people losing their jobs.

To talk of full employment in this climate might be seen as having just a whiff of hubris about it.