V for Vendetta masks: Who's behind them?

- Published

- comments

The sinister Guy Fawkes mask made famous by the film V for Vendetta has become an emblem for anti-establishment protest groups. Who's behind them?

(Spoiler alert: Some plot details revealed below)

From New York, to London, to Sydney, to Cologne, to Bucharest, there has been a wave of protests against politicians, banks and financial institutions.

Anybody watching coverage of the demonstrations may have been struck by a repeated motif - a strangely stylised mask of Guy Fawkes with a moustache and pointy beard.

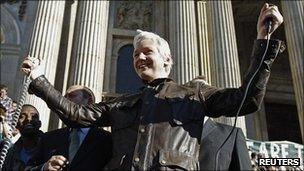

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange arrived at the Occupy London Stock Exchange protest to make a speech wearing one of these masks. He took it off, reportedly at the insistence of the police.

They were thought to have been used first by the notorious hacker-activist group Anonymous in 2008 during a protest against Scientology, but have since spread throughout the global protest movement.

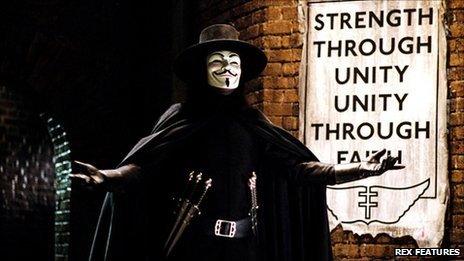

The masks are from the 2006 film V for Vendetta where one is worn by an enigmatic lone anarchist who, in the graphic novel on which it is based, uses Fawkes as a role model in his quest to end the rule of a fictional fascist party in the UK.

Early in the book V destroys the Houses of Parliament by blowing it up, something Fawkes had planned and failed to do in 1605.

British graphic novel artist David Lloyd is the man who created the original image of the mask for a comic strip written by Alan Moore. Lloyd compares its use by protesters to the way Alberto Korda's famous photograph of Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara became a fashionable symbol for young people across the world.

"The Guy Fawkes mask has now become a common brand and a convenient placard to use in protest against tyranny - and I'm happy with people using it, it seems quite unique, an icon of popular culture being used this way," he says.

A curious Lloyd visited the Occupy Wall Street protest in Zuccotti Park, New York, to have a look at some of the people wearing his mask.

"My feeling is the Anonymous group needed an all-purpose image to hide their identity and also symbolise that they stand for individualism - V for Vendetta is a story about one person against the system."

The film of V for Vendetta ends with an image of a crowd of Londoners all wearing Guy Fawkes masks, unarmed and marching on parliament.

It is that image of collective identification and simultaneous anonymity that is appealing to Anonymous and other groups, says Rich Johnston, a commentator on the world of comics.

The 2006 film added a new costume to the fancy dress pantheon

The widespread adoption of the masks was definitely a reaction to the film rather than the book, he argues.

"The book is about one man bringing down the state but the film includes a scene of a huge crowd - making a statement against a faceless corporation."

"The masks were useful for the Scientology protests because it prevented individuals from being recognised," he adds.

Lloyd said that when he and writer Moore created the character of V they had a basic idea of an urban guerrilla fighting a fascist dictatorship but wanted to inject more theatricality into the story.

The mask is bought even in countries where Guy Fawkes is not such a well-known figure

"We knew that V was going to be an escapee from a concentration camp where he had been subjected to medical experiments but then I had the idea that in his craziness he would decide to adopt the persona and mission of Guy Fawkes - our great historical revolutionary."

The masks were originally made by Warner Bros to promote the film and were handed out at screenings. Now they are being sold to everyone from activists to fancy dress enthusiasts.

Rubies Costume Company, which makes the mask, sells around 100,000 a year worldwide, and 16,000 in the UK, according to spokesman Steve Kitt, who seems a little concerned that any association with activists might harm the company's image.

Rubies is dismissive of the idea that Anonymous and other protesters have fuelled demand for the mask, saying it has been successful ever since the film was released.

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange has been associated with the V imagery

Lloyd says he has already heard anecdotes about police in the US searching for the masks in people's houses to be used as evidence of involvement with Anonymous hacker attacks, "which is scary but also ridiculous - you wouldn't prosecute someone for having a t-shirt with Che or CND on it".

Johnston is just back from the New York Comic Con and recalls one incident where a group of V for Vendetta fans, dressed as their hero, unwittingly wandered into the Occupy Wall Street protest and were mistaken for protesters by the police.

Paul Staines, who blogs under the name of Guido Fawkes, said he finds it ironic that anti-capitalist, anti-corporation activists are inadvertently supporting Warner Bros - one of America's 100 biggest companies with profits last year of £1.6bn - by buying the masks.

He thinks the widespread use of the mask "signifies a loss of trust in politics - Guy Fawkes is the most anti-political figure you can pick".

One Anonymous member camping out in the shadow of London's St Paul's Cathedral said she was with a group of 15 people and planned to stay for "as long as necessary".

Sales of the masks make money for Warner Bros

She said that she and others had been wearing the masks, not only to protect their identity but also because it has become a symbol of the movement against corporate greed.

"It's a visual thing, it sets us apart from the hippies and the socialists and gives us our own identity. We're about bypassing governments and starting from the bottom."

Johnston sees the mask as fundamentally a violent image. "It's not a symbol of passive resistance but a symbol of active terrorism - it's about bringing down a government and a country and that could be quite scary and alienating to some people."

The idea of the V mask being appropriated as a political symbol is inherently ridiculous, he suggests.

"It's like assuming you can bring down a government using a light sabre or a He-Man sword."