Why should I get a will?

- Published

- comments

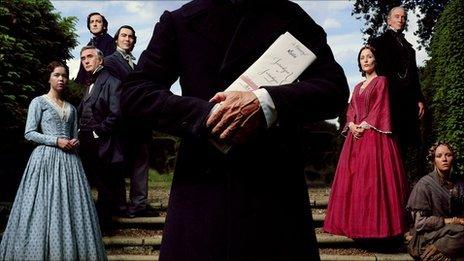

The characters in Charles Dickens's Bleak House battle over a disputed will

Despite this being an age of complicated financial affairs and intricate family relationships, more than two-thirds of people in the UK don't have a will. So why do so many people simply refuse to make one?

Wills, or the lack of, have formed the basis of many a fascinating story. From Dickens to EastEnders, they have made and broken lives, ripped apart families and created millionaires.

But as much as people might be fascinated by others' tales of surprise windfalls or bitter disinheritance, when it comes to our own affairs, it seems we suffer a serious case of ostrich syndrome.

Only three in 10 people in the UK have a will. Last year the Treasury gained £53m from people who died intestate - without a will. The year before it was £76m. And yet the fractured nature of modern families and an increasingly litigious society means making a will has never been so important.

So what is it about signing on the dotted line that leaves people so nervous? And is the whole notion of wills about age or assets?

Lucy Townsend accidentally cut her entire family out of her will

November is Make a Will Month, when the £85 fee that would usually go to the solicitor will instead be donated to Will Aid, a charity that distributes the money to worthy causes. So it seems as good a time as any for me to put my assets in order.

The first thing my solicitor tells me is that making a will does not mean I am about to die.

The next is that I filled out my preliminary form incorrectly, accidentally cutting out my entire family.

The language of wills is confusing. Steeped in history, it is formed on precedents of circumlocution. As mere laymen faced with the already daunting task of contemplating our death, navigating legal jargon makes it all the more stressful.

"The language is getting better," says Nick Hall, of London's Davenport Lyons, the man charged with writing my will. "We are trying to make it clearer, but there are precedents decided by law and the language is part of that."

The role of solicitors is to tell people what things mean, he suggests.

"I have dealt with wills that people have written themselves, from the internet or from shop bought templates, and they have been totally invalid.

"One I saw only had room for one witness signature - it has to be two. Another client I had wanted to leave all his golf clubs to his best friend, but his best friend was the witness - which means that was invalid - he could never get his golf clubs."

Of course, a cynic might argue that solicitors have just a whiff of vested interest in suggesting DIY wills are a legal minefield that should be avoided.

Off-the-shelf wills are popular. They can be quick and cheap and there are plenty that are perfectly valid if filled in correctly. WHSmith has sold more than a million of its £9.99 Will Packs.

Or you could save yourself even that and go fully DIY.

As with any task, the more complicated the parameters, the more likely you are to think about getting a professional in.

By the end of my meeting with the solicitor, I realise making a will is not a harrowing process. I didn't die as I left his office and it's not particularly complicated, but then neither is my situation.

It can be for families where the parents are unmarried and have children. Here things have the potential to become more problematic and not having a will can have devastating effects.

Richard Moore died in 2009, suddenly, from a pulmonary embolism. He did not leave a will.

"After his death, we were advised that as he was not married and had no dependants his estate would be shared equally between his surviving parents," says his brother Dr Jeremy Moore.

"Richard's biological father played almost no part in his upbringing. My mother divorced my father in the early 1970s. We never saw him. He was not part of our lives."

But Richard's biological father accepted his full entitlement.

"It was my mother's responsibility to find my father, pay legal fees and then meet the costs of tracking him down," says Dr Moore. "Then it was not just a question of him having half of my brother's money, we had to sell his home and his possessions - his CDs, DVDs, his clothes - all for this man, a stranger, who didn't even send us a birthday card in our entire lives."

But despite the horror stories there are many people who would rather not face up to making a will.

Stephen Travis and Joanna Thompson have lived together in their Brighton home for 10 years. They have a son, they are not married and they have no will.

"Making a will is not something that I have ever thought about," says Travis. "It isn't a priority. It's morbid and I don't like thinking about it. It's also a tricky thing to bring up without sounding like you want to ensure your inheritance."

But if the worst happened to her partner, Thompson would be left with nothing. The house they share was originally his, and while they have shared the mortgage for 10 years if he died Joanna would have no claim. All Stephen's assets would be passed directly to his three-year-old son. Leaving Joanna to cope on her own until their son comes of age.

Some parents have been forced to effectively sue their own children just so they have enough cash to live.

Worse still - what would happen to their little boy should they both die?

The solicitors who make wills encounter many reasons for reluctance.

Many people just can't face the prospect of contemplating their own mortality, says Charles Neal, partner at Bell & Buxton Solicitors in Sheffield.

"Others don't like trying to decide between family and friends who gets what," says Neal. "Some think it is something that people have to do in old age, some don't like the paperwork."

And the reason for having a will is to make things easier for your nearest and dearest if you do suddenly die.

But I still have not signed my will, because it is thought provoking and sad. Seeing my Last Will and Testament, bound in card and bearing my name, was a strange, almost out-of-body, experience.

I felt like Reggie Perrin. But equally, as soon as it is signed I can put it in a drawer and concentrate on living. Maybe it is not such a big deal after all.