Scientists glimpse inside a Peruvian mummy

- Published

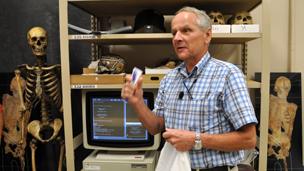

Dr Bruno Frohlich says he hopes the scan can reveal secrets of the mummy's life and death

In a small room lined with shelves of skulls, fossils, bones and antique violins, researchers are using advanced computer imaging to study priceless objects, including a mummy from Peru. So what's inside?

Some patients find CT scanners and other medical imaging devices claustrophobic.

But this lady, a high-born Peruvian woman in her 40s, was not complaining - she has been dead for about seven centuries. And researchers at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History would like to know a bit more about her.

The nameless woman is one of the best preserved Peruvian mummies anywhere, and the CT scanner allows researchers to peer inside her without damaging her.

The CT scanner has already revealed the mummies internal organs are intact, Dr Frohlich says

The scanner uses x-rays to shoot thousands of images of the object in thin slices. Computer software then reassembles the images to create highly accurate, detailed three-dimensional models and reconstructions.

"We could probably do the same with a traditional autopsy," says Bruno Frohlich, a physical anthropologist with the museum, "but there would be nothing left for future generations and it would destroy something that should not be destroyed."

The National Museum of Natural History is one of Washington's most popular, and on a given day its public galleries teem with school children and tourists.

To reach the CT scanner lab, a visitor passes the stuffed elephants, birds, mammals and native American artefacts and takes a lift upstairs into the research wings. Next, there is a long walk through a labyrinth of dim corridors lined with drawers holding thousands of once-living specimens - a crate of whale bones here, a box full of chipmunks there.

Spacesuits and violins

The museum's newest CT scanner, worth a cool $250,000 (£155,472), was donated by global technology giant Siemens in the spring. The company has donated four to the museum since the 1990s.

The device will take images of thousands of slices of the mummy to be reassembled in 3D

"It allows us to connect the dots of history," says Kulin Hemani, a vice-president at Siemens' computed tomography division, explaining the significance of the mummies. "How these people were living, what were their habits, how did they die?"

The CT (computed tomography) scanner has proven invaluable to researchers as it allows them an increasingly high-resolution peek inside the objects and artefacts they study, without having to cut them open or destroy them.

In addition to mummies, researchers here have used CT scanners to examine priceless Stradivarius violins, marine fossils, pottery, aging Nasa spacesuits and more. The applications are innumerable, researchers say.

On Thursday, Dr Frohlich, a native of Denmark who has been with the museum since 1978, brandished a set of fossilised reptile jaws between 50 million and 100 million years old.

Heads and bodies

Because the rocky sediment lodged in cracks and crevices in the jaws has a different density than the fossilised bone, the CT scanner will allow researchers to remove the sediment digitally by isolating it from the bone in the digital images, says Dr Frohlich.

The device can help match mummy bodies to their separated and mixed-up heads, Dr Frohlich says

That offers a picture of the scrubbed fossil without the risk of harming it with physical tools, he says.

Researchers ran a Nasa spacesuit through the CT scanner in order to learn how its polymer fibres were breaking down with age, in order better to preserve it for the future, says David Hunt, another museum anthropologist.

And recently, researchers in Mongolia sent Dr Frohlich a collection of mummies - with the bodies separated from the heads and no records to match them up.

This was fine, Dr Frohlich says, because the CT scanner will allow him to reassemble the mummies by matching the bone density of each specimen.

Natural mummification

The woman mummy, discovered in Ancon, Peru, arrived in the museum's collection between 50 years and a century ago, he says.

CT scan investigation could reveal how the woman lived - and died

When she died, she was placed upright in what looks like a red dress with an elaborately crocheted fringe, sitting cross-legged. Rather than decompose, her body was mummified by the cold, dry mountain air and wind.

The process is called natural mummification, as opposed to the classic Egyptian mummification in which the body is eviscerated and treated with chemicals.

Researchers have only recently begun to investigate her, but Dr Frohlich says the CT scanner has revealed her internal organs are intact.

That will eventually enable investigators to learn about her nutrition and diet, her general level of health, whether she suffered illness, whether she had overcome disease, whether she had broken bones or other injuries, and more.

"Maybe she's pregnant," says Dr Frohlich. "Who knows?"

Such studies add to the human understanding of ancient peoples, he says.

"We should learn about our history. Why did cultures and civilisations start up and especially why did they disappear? Is it economy or is it environment? We may be able to help our own society to learn, which will help us in our decision making."