Thankful villages: The places where everyone came back from the wars

- Published

- comments

The mass slaughter of 1914-18 robbed the UK of a million lives, leaving no part of the country untouched. But there was a tiny handful of settlements where all those who served returned home.

With its rows of ramshackle yellow stone cottages, set amid undulating Cotswold hills, the village of Upper Slaughter belies the violence of its name.

In hazy autumn sunlight, this corner of Gloucestershire might well have been rendered in watercolour. All the components of tourist-brochure Britain are here - the red phone box, the winding lanes, the wisteria draped around the windows.

But one normally ubiquitous feature is missing. Unlike the overwhelming majority of British settlements, Upper Slaughter has no war memorial.

Instead, tucked away in the village hall are two modest wooden plaques. They celebrate the men, and one woman, from the village who served in both world wars and, in every case, returned home.

For it is not only its postcard charm that offers pacific contrast to the name Upper Slaughter. It is that rarest of British locations, a "thankful village" - the term coined in the 1930s by the writer Arthur Mee to describe the handful of communities which suffered no military fatalities in World War I.

The Mayor of Thierville in France, Bertrand Simon, explains why there is no monument to the dead in the village

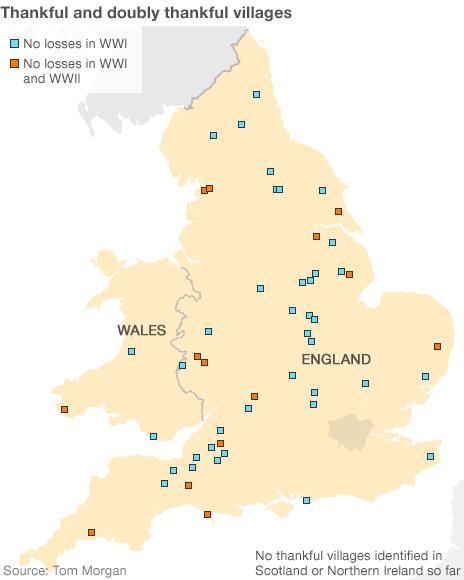

Mee identified 32 such places, a figure that has been revised upwards in recent years to 52. Of these, just 14 have, like Upper Slaughter, come to be known as doubly thankful - also losing no-one from WWII.

Somehow, these rare outposts - as disparate and evocative-sounding as Nether Kellet, Lancashire; Woolley, Somerset; and Herbrandston, Pembrokeshire - were shielded from the worst ravages of the first half of the 20th Century. Some of those they sent to fight may have returned home badly injured or deeply traumatised, but all came back alive.

The scale of their good fortune is extraordinary. A million British lives were lost from 1914-18 in Europe's first experience of industrialised, total warfare. No Scottish community appears to have been left unscathed, and no thankful villages have been identified in Ireland, all of which was still part of the UK during WWI. In England and Wales, the 52 so far singled out are dwarfed by over 16,000 which paid the highest sacrifice.

In terms of the UK's collective memory of 1914-18, they represent a striking anomaly. Through history lessons, war poetry and popular culture, the abiding modern portrayal of WWI is as a devastating event of industrial-scale carnage.

Upper Slaughter has no war memorial at its heart

And yet this handful of communities, whose sons emerged alive from the horrors of the trenches, offers a unique insight into the experience which shattered the pre-WWI order and, in turn, transformed society irrevocably.

One man who understands this is Tony Collett, an energetic 80-year-old who has lived and worked in and around Upper Slaughter all his life. Tony was too young to have served in either world war. But after WWII he hand-painted the lettering on the plaque celebrating the 36 men from the village who came home safely.

Standing in the village hall, he looks up, pauses, and places a hand on the wooden sign, before telling its story.

It was erected in 1946 alongside a similar marker put up to give thanks for the 24 men and one woman of Upper Slaughter who returned in 1918. Both the WWI and WWII versions included the name of Tony's father, Francis George Collett, the village's resident handyman, universally known by his middle name. Born in 1895, George had the rare distinction of serving in two world wars.

Tony Collett points out his father's name on the plaque he hand-painted in 1946

After enlisting at the age of 19, he was sent to Mesopotamia, now Iraq, where 92,000 of the 410,000 Commonwealth troops died. As a member of the Territorial Army, Sgt Collett was one of the first to be called up in 1939, coming under fire before long as an anti-aircraft gunner with the Royal Artillery on the home front.

But it was not only those in uniform like George whose lives were at risk. On 4 February 1944, Upper Slaughter faced an attack from the sky, with incendiary bombs raining down on the village.

"I saw it through the skylight," recalls Tony, who was 14 at the time and sharing a room with his sister. "The first thing we did was dive down under the blankets.

"We came out and saw all these flames. We were dodging fires all the way down the road."

It was 05:30 GMT, and the village was burning. Several cottages and barns had been hit. But the people of the village quickly assembled, gathering water and sand to douse the flames. Though the damage was severe, Upper Slaughter's luck held - no-one was killed.

In 1946, it seemed natural to put up another plaque. The village hall had been acquired by the local Witts family after WWI to mark the armistice. Newly demobilised George, the village's odd-job man, church sexton and occasional undertaker, was given the task of creating a second marker to give thanks for the men who had just come back.

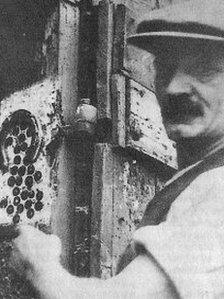

George Collett (left), pictured in 1937, served in two world wars

With his son assisting, George carved the wooden plaque, styling it to match that from 1914-18. Tony then carefully painted the 36 fortunate names.

Another sign, on the other side of the hall, was fashioned from brass to commemorate the "distinguished conduct and promptitude" shown by Upper Slaughter's residents on the night of the incendiary bomb raid.

Every time they passed the building, the people of the village were reminded of their incredible luck. And yet amid the wreckage of make-do-and-mend austerity Britain, with so many communities shattered and families destroyed, it felt unseemly to discuss this.

After all, during the first half of the 20th Century, Upper Slaughter was very much the exception. While people in this corner of the Cotswolds were quietly grateful for what they had escaped, the vast majority of their compatriots were adjusting to the most profound of losses.

For every village like Upper Slaughter there was another like Wadhurst, East Sussex - a place of just over 3,500 people which lost 149 men in WWI, according to research by the historian Paul Reed, author of Great War Lives.

On a single day in 1915 at the Battle of Aubers, 25 men from Wadhurst were killed - just under 80% of all those who went forward into no-man's land, and almost certainly the heaviest per capita casualties of any community in the UK for one day's battle. The majority of the fallen had no known grave.

Indeed, according to the WWI historian Dan Snow, it was often small communities, villages and hamlets in which the psychological burden of the carnage's aftermath was most painfully felt.

Largely to blame for this, Snow believes, was the system of Pals Battalions - units of friends, work colleagues and relatives who had been promised they could fight alongside each other when they enlisted amid the patriotic fervour of 1914.

The battalions were a useful recruiting tool for War Secretary Lord Kitchener, who believed that mobilising large numbers of enthusiastic recruits quickly was the best method of winning the war.

But the reality of the trenches, where thousands of men could be wiped out in a single day, meant that small communities could face disproportionate levels of bloodshed within a matter of hours.

Of about 700 "pals" from Accrington, Lancashire who participated in the Somme offensive, some 235 were killed and 350 wounded within just 20 minutes. By the end of the first hour, 1,700 men from Bradford were dead or injured. Some 93 of the approximately 175 Chorley men who went over the top at the same time died.

It was a pattern repeated many times - and on each occasion, a town or village was deeply wounded, instantly. The "pals" system was phased out in 1917, but not before it left an indelible mark on the British consciousness.

"They had to stop that practice because it was so unbelievably destructive," says Snow, whose great-grandfather Sir Thomas D'Oyly Snow was a general at the Somme.

"When you let brothers serve together, it can be devastating for a whole community. It was a war that touched everybody in the British Isles. That's what total war means."

The UK may have lost 2.2% of its population, but in other belligerent nations the toll was even higher. France lost 1.4 million, some 4.3% of its citizens.

The French equivalent of a thankful village is even more extraordinary. Thierville in Normandy has not lost any service personnel in France's last five wars - the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, World Wars I and II, Indochina, and Algeria.

Of course, even those in the thankful villages in the UK did not escape the hardships and disruption imposed by total war. By 1918, rationing was in force and everywhere on the home front would take many years to recover.

Likewise, the fortunate veterans who made it home alive were scarcely unscathed. Many were permanently damaged by their experiences, whether physically or mentally. By the end of WWI, the Army had dealt with 80,000 cases of "shell shock" - psychological trauma caused by war experiences.

"Soldiers can return, but it might be with their bodies or their psyches scarred," says Peter Englund, author of The Beauty And The Sorrow: An Intimate History of the First World War.

Nonetheless, given the scale of the losses, and the fact that virtually no family was left intact, it is scarcely surprising that the notion of thankful villages proved comforting to a British public which was still reeling from the war long after the armistice.

The phrase was first used by Mee - a celebrated writer and journalist best known for his 1908 Children's Encyclopaedia - in The King's England, a 1930s series of books offering a guide to each of England's counties.

By this time, a war memorial was a feature of virtually every settlement in the country. Mee was struck by the tiny proportion that did not have one, and the notion of the thankful villages was born.

In an interwar Britain convulsed by a fresh set of shocks - the great depression, mass unemployment, the rise of fascism in Europe - it's hardly surprising that readers looked on such places as a nostalgic reminder of an apparently simpler time before August 1914.

Mee appears to have understood this, his prose on the subject assuming a wistful tone. "Thirty men went from Catwick to the Great War and thirty came back, though one left an arm behind," he wrote of one village in a volume on the East Riding of Yorkshire.

And yet somewhere along the way, in the slipstream of a second global conflict, the notion slipped from the public consciousness - even in places like Catwick.

Though it never had a war memorial, the windswept village had a commemoration of its own. At the outset of WWI, the village blacksmith, John Hugill, nailed a lucky horseshoe to the door of his forge. Around it, for each man who went to the war, he nailed a coin. When WWII broke out, he did the same again.

As Catwick was to prove doubly thankful, it was a remarkable monument. And yet when Hugill's workshop closed, the coins and the horseshoe were taken away from the door.

All were fixed to a board and eventually passed onto Hugill's grandson, now 60 and also called John Hugill, who still lives in Catwick, where he runs an engineering firm.

He has vowed never to let the memento leave the village and hopes to find a way to put it on public display. Hugill was too young to know his grandfather, while his father - who served as a Sergeant-at-Arms in the Home Guard during WWII - was reluctant to speak about his wartime experiences.

"All they wanted to do was forget it," Hugill says.

"When they're gone, you think, 'Why didn't we talk to each other about it?' But there was a big age gap - there'd been such a huge change in culture."

Catwick's blacksmith nailed a coin for every man who went to war - all returned

Tony Collett experienced something very similar. It took decades, he says, for Upper Slaughter's remarkable good fortune to be widely discussed in the village. Only in the past 10 years or so, he reckons, has this semi-superstitious reluctance to give voice to the village's special status fallen away.

Tony attributes this to the characteristic stoicism of his father's era. Whatever terrifying and extraordinary sights he may have seen in battle, George, typically for his generation, rarely spoke of them.

"It's one of these things," says Tony. "Because the war and its aftermath were all around us, you needed to just live with it and carry on with your life.

"It was only in recent years that people really started to realise there were these thankful villages. It was never spoken of in my younger days."

As the country picked itself up, Tony entered the Royal Marines for his two years' National Service. On Remembrance Day 1950 he was in uniform in Whitehall as the King laid a wreath at the Cenotaph.

After returning to civilian life in the family building firm, Tony would travel each Remembrance Sunday to the war memorial of the neighbouring village, Lower Slaughter.

As he looks out over lanes and buildings he has known all his life, Tony knows Upper Slaughter is no longer the intimate, tightly-bound community in which he grew up. The cottages are no longer within the financial reach of handymen and part-time undertakers. An influx of second-home-owning weekend residents has meant that the villagers are no longer intimately acquainted with each others' business, he says, for better or worse.

But Tony is aware that for decades the community retained a sliver of pre-WWI innocence, long after the rest of the country.

The generations who grew up after the wars, for whom the memories of the nation's loss are less raw, have proved more willing to discuss the subject. And, as a result, the past decade has witnessed a growth in awareness of thankful villages.

Just 14 villages were lucky enough to escape losses in WWII as well as WWI

Battlefield tour guide Tom Morgan, 64, had been a WWI enthusiast all his life, and dimly recalled during his boyhood reading a letter in a newspaper which referred to thankful villages.

The story had always nagged at his memory, and in the late 1990s, Morgan posted on a history internet discussion forum asking if anyone else was aware of it, to no avail. However, the post remained one of the only references to thankful villages on the internet, and years later he was contacted through the site by another amateur historian.

The two began researching the subject, and, along with another enthusiast, began producing a website identifying thankful villages. As well as investigating the places identified by Mee, the men were contacted by readers who tipped them off about other possible locations.

By the end of 2010, the number of verified thankful villages had risen to 52, but not before Morgan and his colleagues had undertaken much painstaking research, trawling through local newspapers, church records and the archives of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Their efforts mean a hitherto neglected historical curiosity has been given additional prominence.

For Morgan, the significance of the thankful villages is their unique mindset - one denied to the rest of Britain by the million bereavements it endured in WWI. The cultural narrative of the conflict is as a series of grossly negligent betrayals of heroic young men by the era's political and military establishment, he says.

"The First World War changed society," Morgan argues. "Everybody began to have doubts about the ruling class who were running the country by accident of birth, not ability. People decided that they'd like a little bit of a say in their own destiny.

"But the thankful villages were able to just carry on. Elsewhere, whole communities may have been shattered, but here you have these magical places not bearing any mental scars."

Inexplicable patterns can be composed from the list of thankful villages - Somerset was particularly fortunate, for instance, boasting nine such communities, while neighbouring Wiltshire has none at all.

But there seem to be few obvious reasons why some places were luckier than others. Servicemen like George Collett, risking in his life in Mesopotamia, were hardly out of harm's way. Nor were the thankful villages any less forthcoming when it came to providing volunteers. Arkholme, Lancashire, sent 59 men to fight in WWI, all of whom appear, incredibly, to have returned.

Instead, they seem merely to have been lucky. As one researcher, Rod Morris, has observed, 21 personnel from Rodney Stoke, Somerset, may have all come back intact - yet of 73 sent by neighbouring Draycott, 11 were killed. What the thankful villages tell us, if anything, is that the prospects of survival are entirely arbitrary.

They may be few in number, but it is possible that more thankful villages are out there. Several of those on Morgan's list are there purely by virtue of a casual reader's curiosity being nagged by their lack of a local war memorial.

One of those was Minting, a small outpost in Lincolnshire with a population of 167 to which former Royal Army Educational Corps officer Roy Griffiths and his wife Karen had retired.

With their shared military background - Roy served for 24 years, while Karen's father had been in the RAF - both were puzzled.

"One of the things I'd noticed about the village was that it didn't have a war memorial," Roy, 71, recalls. "I couldn't believe that Minting didn't suffer any losses in World War I, even though it's small.

"When we asked around, all we were told was that there wasn't a war memorial and that was that."

The pair set off on a trail, trawling old copies of the local newspaper and studying census and electoral roll data.

Minting had sent 10 men to WWI, it transpired, and all of them returned. In WWII, the Griffiths found that nine had fought - although one, Pte Raymond Camp of the Lincolnshire Regiment, had been killed in action in 1943. Thanks to the couple's efforts, a pair of plaques now hang in the parish church, giving thanks for the 18 men of the village who came back safely and commemorating the loss of Pte Camp.

Upper Slaughter was hit by incendiary bombs in an air raid

Wandering around Upper Slaughter, the memorial plaques may be displayed modestly inside the village hall, away from public view, but virtually every lapel carries a poppy.

And the very recent past has given Upper Slaughter yet more to be thankful for.

As British forces embarked on their first campaigns of the 21st Century, the village was once again represented. A son of Upper Slaughter, Lt Fred Keeling, completed two tours of Iraq and one of Afghanistan with the Royal Artillery. When he left the Army in 2008 after five years, the community's unbroken record of good fortune remained intact.

For his family, it was a very different experience to that of anxious parents in previous conflicts. Unlike in the 20th Century's world wars, they could take no comfort from the knowledge that virtually every other household shared their plight.

But Richard Keeling, 63, Lt Keeling's father, says Upper Slaughter never forgot about his son. Its remarkable legacy from two world wars saw to that.

"We've lived here for 20 years so we've always known the history," Richard says. "We know we're from a very special village. And we're very relieved that we haven't broken the average."