Mumia Abu-Jamal: Man, myth and the death penalty

- Published

Across the world, supporters protested to free Mr Abu-Jamal

Almost 30 years after his conviction for killing a police officer, Mumia Abu-Jamal has had his sentence revised and will no longer be a death-row inmate.

For many Abu-Jamal's case was less about the crime than it was about the man, and the moral justification of the death penalty.

When Mumia Abu-Jamal was convicted in 1982 of killing Daniel Faulkner, the courtroom was only half full.

"Outside of Philadelphia, the case was not a big deal at the time," says Marc Kaufman, a journalist who covered the story for the Philadelphia Inquirer. "Interest in the case was significantly less than what would come later."

What came later was a global movement. Abu-Jamal became an international symbol for institutional racism and judicial abuse and a cause celebre for anti-death penalty advocates. His face was a prominent image at anti-death penalty rallies, progressive gatherings and Beastie Boys concerts.

By the 1990s, his name had become a shorthand for injustice and racism within America. In doing so, his supporters turned Abu-Jamal from a man into a myth.

Now, Abu-Jamal is off death row, serving a life sentence with no chance of parole. The decision came this week after years of appeals, cemented when the Philadelphia district attorney declined to pursue a new sentencing trial after a higher court declared the death penalty verdict invalid.

Poster boy

For supporters of the family of Daniel Faulkner, this case has always been about the death of the officer and the facts of the murder presented at trial: witnesses who placed Abu Jamal at the scene, Abu-Jamal's gun recovered nearby and a bullet from Faulkner's weapon lodged in his ankle.

That numerous appeals from the Abu-Jamal legal team were denied by the courts only steeled their resolve that the facts were on their side.

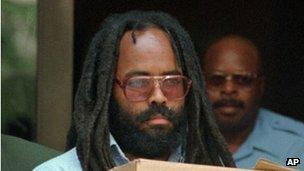

Mumia Abu-Jamal in 1995

Supporters of Abu-Jamal maintain his innocence, and say he was a victim of a corrupt system. For them, the focus of the case is less about the specifics of that night than the institutional problems within American law enforcement.

The circumstances of the trial spoke to structural issues with the criminal justice system long argued by anti-death penalty advocates, says Shari Silberstein, executive director for Equal Justice USA. An all-white jury for a black man. A judge with a reputation for being tough on minorities. A city fraught with racial tension.

Though there were problems with Abu-Jamal's trial, other cases have had more clear-cut examples of wrongdoing, incompetence and bias, says Richard Dieter, director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

But none of those cases had defendants who so neatly embodied the intellectual outrage activists felt about the capital punishment.

"There's general opposition to the death penalty, and it needs a face, and a cause," Mr Dieter says.

Abu-Jamal provided that face perfectly. His public profile literally made him a poster boy for those who found capital punishment abhorrent.

Prior to his arrest, Abu-Jabal had been a public radio host and a political activist.

After his conviction, he wrote several books from jail - vivid accounts of prison life and intellectual attacks on the criminal justice system, but little about what happened the night Daniel Faulkner died.

"He was a very prolific writer and communicator to the outside world, and people were able to hear his voice and perspective of prison life in a way that people hadn't before," says Shari Silberstein.

In the 90s, at a time when support for the death penalty , externalwas at an all-time high, the "Free Mumia" movement was also peaking, providing clear rallying point for those who believed the system was unfair.

To his supporters, Abu-Jamal is not a hard-luck case or a simple victim of mistaken identity. He is a political prisoner.

'No resolution'

As the myth of Mumia grew, Marc Kaufman says, the facts of the case became less significant.

.jpg)

The slain officer's widow stood with Philadelphia's prosecutor as the death penalty was revoked

"Because he is articulate and appealing, there are a lot of people who were attracted to him," says Mr Kaufman. "That's fine and appropriate, but what I personally found disingenuous as the years went on was that there was a revisionist history as to what happened" on the night Daniel Faulkner was shot.

The theories and speculation that supporters say proved Abu-Jamal was framed didn't stand up to scrutiny, external, says Mr Kaufman, who reported on many of the claims.

"Thirty years of appeals, and there's no consensus about whether he's an innocent man who's been railroaded because of race or if he's a guilty murderer," says Frank Baumgartner, professor of political science at the University of North Carolina. "There's no resolution in that issue."

And it looks like there never will be. Part of the reason that the district attorney declined to go forward with a new trial is that after 30 years, many of the original witnesses have died. The case has been so divisive that each side has their own set of facts, and there's no sign of a detente.

Life sentence

In the end, this much is true: an appeals court did find that the sentencing jury that handed Abu-Jamal the death penalty had received invalid instructions.

Regardless of whether he was a political prisoner or cold-blooded killer, the court said, justice was unfairly applied.

To opponents of capital punishment, that possibility, not the facts of an individual case, is the point.

"I think every case is a good case for people who opposed the death penalty," says Franklin Zimring, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley. "When you start putting the system under a microscope, the death penalty looks both unnecessary and problematic."

That's cold comfort for Maureen Faulkner, who gave her permission to the district attorney before he made the decision to take Abu-Jamal off death row. After the official announcement, she noted the severe financial, emotional, and psychological toll this fight has taken on her family.

"My family and I have endured a three-decade ordeal at the hands of Mumia Abu-Jamal, his attorneys and his supporters, who in many cases never even took the time to educate themselves about the case before lending their names, giving their support and advocating for his freedom," she said.

She has also been a prisoner.

"The death penalty is often a lengthy and disappointing quest that does no one, really, any service," says Mr Dieter. "Once you get started on the death penalty, all bets are off. It's all about the defendant and nothing about the victim for years. It's a tease at best. At worst it's a disservice."