America's suburbs: Key to the 2012 election

- Published

A suburban small business owner is unimpressed with President Obama's speech, and laments the presidential campaigning so far.

Economic and racial diversity in the American suburbs is growing rapidly. And so is the power of the suburb to determine the presidential election. As part of the BBC's continuing series on suburban Levittown, Pennsylvania, we take a look at suburban influence.

When candidates for president seek photo-op backdrops to emphasise their vision and values, they invariably invoke images of small town squares and rural Main Streets.

The first three primary contests in this year's election, Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina, reinforced this Thomas Jefferson-meets-Norman Rockwell ideal. News crews followed the candidates across landscapes of farmland, diners, rural factories and county fairs.

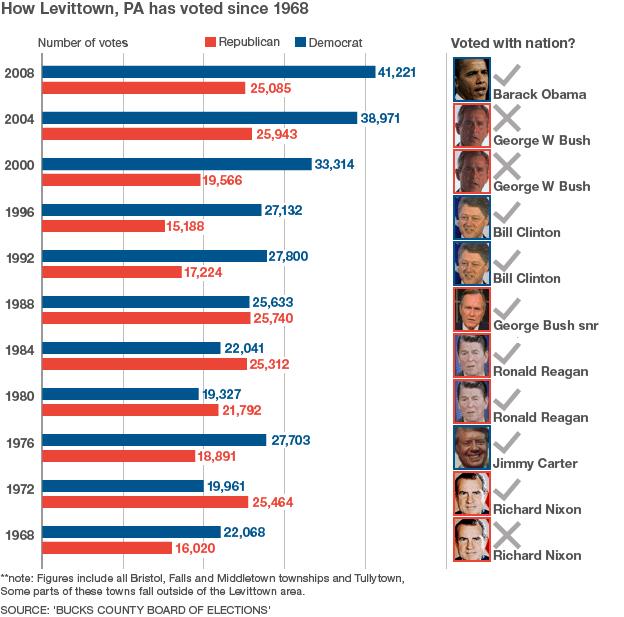

But this is not the America that wins presidential elections. That America lives in its suburbs, including the iconic Levittown, Pennsylvania.

For the last six presidential contests, since Democrat Michael Dukakis invited cameras to watch him working around his suburban Boston yard, the more moderate voters in the American suburbs have decided which candidate went on to live in the White House.

More recently, about 35 "swing" suburban congressional districts have determined which party controls Congress.

Don't expect this election cycle to be any different.

Growing power

The United States is an ever-more suburban nation. Well over half of the population, and half of the national electorate, now resides in the suburbs.

Their growth has changed the calculus of political contests at every level, from the presidency to local school boards.

Even the early primary states are not as homogeneously rural as they once were, and their changing composition has political consequences.

This year, Mitt Romney, a relative moderate in a conservative Republican field, nearly won Iowa by dominating not just the state's cities but the suburban rings around them.

The Boston suburbs that now extend northward from Mr Romney's home state of Massachusetts widened his victory in New Hampshire. His performance in suburban South Carolina towns, and those costal enclaves to which former northern suburbanites have retired, kept him from being blown completely out of the state by Newt Gingrich.

And among moderates, who are clustered in the suburbs and who will make up a far larger share of voters in the upcoming Florida primary, Mr Romney actually beat Mr Gingrich.

Economic unrest

More important than the sheer power of suburban population is the growing economic, ethnic and political diversity of the suburbs.

The Hofstra Suburban Survey, external, which periodically polls 1,000 US suburbanites, has revealed growing division within suburbs, like both Levittown, PA and its sister city, Levittown, NY, each long saddled with its own stubborn myth of uniformity and prosperity.

In 2011, 40% of survey respondents reported living "paycheck to paycheck" most or all of the time.

Twenty per cent had lost a job since the last election, and 59% more knew someone who had. Thirty-eight percent knew someone who had lost their home to foreclosure.

Suburban residents are far from a monolithic voting block

These rates are marginally better than those of cities and rural areas. Yet given the size of the suburbs, the absolute number of distressed suburbanites dwarfs their urban and rural counterparts, and absolute numbers win states.

So when President Barack Obama or his opponent present their plans for relief and recovery, they are speaking to suburbanites in crisis, whether they know it or not.

These distressed, often working-class residents may make the suburbs more receptive to an economic populist message.

Mr Obama clearly laid out these themes in his State of the Union address, calling for a higher tax rate for people who make over a million dollars a year, and "an economy where everyone gets a fair shot, everyone does their fair share and everyone plays by the same rules."

Pundits predict that populism will be a main theme of his campaign.

Meanwhile, Mr Romney's rivals have characterised him as affluent and out of touch with ordinary citizens. The tax returns he released this week shows he paid 13.9% in taxes after making $21.6m (£13.9m) in 2010, a rate the White House says is lower than most middle-class Americans.

The populist line of attack may play better than expected in the supposedly anti-tax suburbs. When we presented a series of policy proposals to our survey respondents, we found a surprising ambivalence among suburbanites when we asked about increasing taxes on the rich.

Fifty-seven percent supported "reducing personal income taxes on all Americans", but 59% also supported "raising personal income taxes on wealthier Americans", with over half of respondents supporting tax increases on incomes of $250,000 (£160,390) or more.

At a moment when many Occupy Wall Street encampments were facing off against local police, 49% of those suburbanites who had heard of the movement viewed it favourably.

Among suburbanites who made less than $30,000 (£19,246), the movement was still more popular (56%), as well as with those who were black or latino (59%).

Separate worlds

Race and ethnicity, in fact, mark a chasm of political opinion on a number of issues. In United States metropolitan areas, half of the African-Americans, Asian-Americans, latinos and immigrants now live in suburbs, not cities.

But segregation, especially white-black segregation, has only eased incrementally in this era of diversification.

Suburbanites still largely live in separate neighbourhoods, attend different schools and earn unequal median incomes, reflecting past and present patterns of structural racism.

So it should come as little surprise that the political opinions of racial minorities differ markedly from those of whites.

When compared to whites, minority respondents of our suburban survey are more likely to favour raising federal spending to fund the creation of "green jobs" (72%, v 47% for whites) and expanding unemployment benefits (64% v 49%). They are also less likely to favour cutting government spending generally (52% v 77%).

Minorities in the suburbs are more likely than whites to agree that "the country should do whatever it takes to protect the environment" (69% v 57%), to believe that there is solid evidence for climate change (77% v 53%) and to identify climate change as a serious problem (83% v 53%).

They are more likely to approve of Barack Obama's performance, and to express a preference for his re-election.

It's the rise of minorities, including immigrants, that accounts for much of the Democratic gains in suburbs that had been rock-ribbed Republican until the early 90s.

These divisions will come to the fore on an election night, which may hold surprises for both parties.

News networks and websites will illuminate their maps state-by-state with the party colours, focussing on battlegrounds like Ohio, Nevada and Florida. Below the state level, county returns will demonstrate the continuing and decisive impact of suburban political power.

But digging still deeper, into the social and political fabric of suburban neighbourhoods reveals a fascinating heterogeneity - of ethnicity and income, of political opinions, and finally of visions for the nation's future.

In the end, the Levittowns will have the last word.

Lawrence Levy, former chief political columnist for Newsday and PBS public affairs show host, is executive dean of the National Center for Suburban Studies at Hofstra University

Christopher Niedt is Academic Director of the National Center for Suburban Studies and Assistant Professor of Social Research at Hofstra University