Asma al-Assad and the tricky role of the autocrat's wife

- Published

- comments

Should Mrs Assad disown her husband?

Asma al-Assad has been condemned for supporting her husband, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, as the bombardment of her family's home city, Homs, goes on. But do autocrats' wives ever rein in their husbands?

The first public intervention of British-born Asma al-Assad, 36, since the uprising began in Syria nearly a year ago was an email from her office to the Times newspaper in London, external.

In it she expressed her support for her husband, the president, while stating that she "comforts" the "victims of the violence".

It's estimated by human rights groups and activists that more than 7,000 people - 2,000 members of the security services, and 5,000 others - have been killed in the unrest, and Syrian opposition supporters promptly condemned Mrs Assad's "hypocrisy".

But her stance should come as no surprise, says Rime Allaf, an associate fellow of Chatham House, the London foreign affairs think tank.

"Why are we shaming her and saying she should do something? There was never any question that she would do anything else.

"Even if, deep down, she was not happy with what's happening, she wouldn't be able to do anything about it.

"And even if, between four walls, she told him 'I don't approve of this', we wouldn't know about it. Let's be more realistic about this."

But there have been examples where wives have stood up to their authoritarian husbands.

In the early 1990s, Susana Higuchi condemned her husband, Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori, as a "tyrant" and he responded by divorcing her and giving the status of First Lady to his daughter.

He dismissed the nation's parliament and judiciary, with the help of the army. Higuchi failed in her attempts to become a politician, but in 2009 her ex-husband was sentenced to 25 years in prison for human rights abuses.

Higuchi was an inspiration to women, says Dr Jelke Boesten, a fellow of the US Institute of Peace in Washington.

"It was very brave and temporarily it was very important but her husband was far stronger politically and he had the army behind him and popular support. Although she temporarily won the support of feminist organisations, that was a small part of society."

There are contrasting examples in Africa of female powers behind the throne, says Richard Dowden of the Royal African Society.

"Sally Mugabe was a really soothing, sensible influence on [her husband, Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe] and many people trace his going completely over the top to after she died. Up until then she was the one that restrained him. That is the perception, at least."

When he married his second wife, Grace, the perception is that it all changed, says Mr Dowden, as she embraced the extravagant lifestyle commonly associated with spouses of very wealthy, autocratic leaders.

But Grace is not thought to have had political influence, unlike Simone Gbagbo, wife of deposed Ivory Coast leader Laurent Gbagbo, who is awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court on four charges of crimes against humanity.

"Simone Gbagbo was a more militant version of him," says Mr Dowden. "As a politician he was a bit shifty but she was really hardline and used language that Gbagbo himself would not have used.

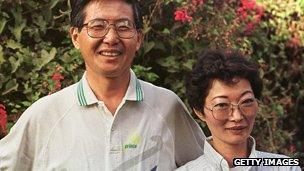

The Fujimoris divorced after she called him a tyrant

"She had a formal political role as well as being the president's wife. She was always in the newspapers and a really rabid anti-foreigner."

There are cases where the wife is a malign influence but mostly it's not the case, says Daniel Chirot, author of Modern Tyrants: The Power and Prevalence of Evil in Our Age. In fact, wives are often unfairly blamed for the actions of a leader, due to a kind of prejudice that holds them to higher standards.

Columnist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown agrees that women are sometimes judged unfairly, but anyone who stands by a dishonourable man with the power to make or break a nation fully deserves blame and punishment, she says.

She believes there are "true Lady Macbeths" like Madame Mao, partly responsible for the Cultural Revolution, or Mira Markovic, widow to Slobodan Milosevic and regarded as a key influence on him.

But the silent wives also deserve condemnation, in her view.

"We don't know if they're victims. I see the difficulties for them but if something like this [in Syria] is going on, for me it's unforgivable. It could be that Asma is under terrible pressure, that she's been told that if she doesn't do this she will be in trouble.

"But both Suzanne Mubarak [wife of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak] and Asma are powerful women. They're not put upon or oppressed women."

Unlike the wife of the late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, who didn't have much of a presence, others like to present themselves as modern Arab women, says Ms Alibhai-Brown. Yet they allow themselves to be silenced when they should speak out or act.

"The biggest rulers in the Ottoman Empire were always very easily manipulated by their wives and mothers, so women could play a part, but since then we've gone backwards.

"It can't be possible that today they are all too oppressed."