How Germany lost the WWI arms race

- Published

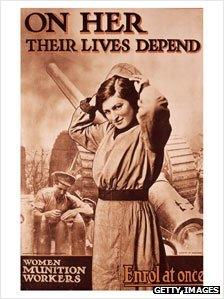

A new, mostly female workforce populated the factories of UK and France to solve a shell crisis that had threatened to defeat the Allies in World War I.

History tells us that a general can move and feed an army as efficiently as he likes but the real litmus test is the battlefield.

All the energy he expends getting his men to the front line fit and healthy counts for nothing if they don't have the right equipment.

What they need, above all, is sufficient ammunition - yet there were moments during the war when a shortage of artillery shells meant the guns almost fell silent.

Given the unprecedented scale of the conflict, it was bound to take time for each side's peacetime armaments industry to adjust.

Each of the major combatants, moreover, had its own limits to production.

Germany lacked the necessary raw materials to make cordite (the vital propellant for bullets and shells) and explosives.

Austria-Hungary was hampered by a lack of rail transport and rail infrastructure.

Britain had a manpower shortage and a paucity of acetone, the key component for making cordite.

And France, in the early years, had to make up for the loss of much of her industrial heartland to the advancing Germans.

None of these factors was particularly pressing while the war was still one of movement. But as soon as it settled down in late 1914 to stalemate, with the trench line stretching 475 miles (765jm) from Nieuport in Belgium to the Swiss border, artillery shells were needed in ever greater quantities to force a breakthrough.

In March 1915, at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, the British fired more shells in a single 35-minute bombardment than they had during the whole Boer War. Britain had enough guns but it was fast running out of anything to fire, and those shells that were available often failed to explode or burst prematurely in the gun barrel.

By May 1915, so serious was the "shell crisis" that most British guns had been reduced to firing just four shells a day and it seemed as if the war was going to be lost, not in the trenches of Flanders but the factories of Britain.

The scandal saw the downfall of Asquith's Liberal government and its replacement with a coalition, although Asquith stayed on as prime minister.

Lloyd George became the head of a new Ministry of Munitions, tasked with increasing the supply of artillery shells to the British Expeditionary Force.

The new ministry set about building munitions factories across the country, and transforming the civilian economy to one completely geared towards war.

It also, crucially, tasked the Manchester-based chemist Chaim Weizmann with producing large quantities of acetone from readily available raw materials. It had previously been made chiefly from the dry distillation of wood; hence most of Britain's acetone was imported from timber-growing countries like the United States.

In May 1915, after Weizmann had demonstrated to the Admiralty that he could use an anaerobic fermentation process to convert 100 tons of grain to 12 tons of acetone, the government commandeered brewing and distillery equipment, and built factories to utilise the new process at Holton Heath in Dorset and King's Lynn in Norfolk.

Together, they produced more than 90,000 gallons of acetone a year, enough to feed the war's seemingly insatiable demand for cordite. As a result, shell production rose from 500,000 in the first five months of the war to 16.4 million in 1915.

By 1917, thanks to the new munitions factories and the women that worked in them, the British Empire was supplying more than 50 million shells a year. By the end of the war, the British Army alone had fired 170 million shells.

France's transformation of its armaments production was even more successful. By importing coal from Britain and steel from the United States, releasing 350,000 soldiers to the war industries, and bolstering them with more than 470,000 women, it was able to increase its daily output of 75mm shells from 4,000 in October 1914 to 151,000 in June 1916, and that of 155mm shells from 235 to 17,000. In 1917 it produced more shells and artillery pieces per day than Britain.

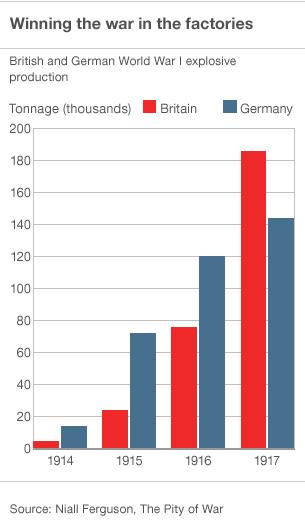

Germany had started with an industrial advantage over both Britain and France - chiefly because it led the way in steel production, and in many branches of chemicals and engineering - and its output of shells in 1914 was 1.36 million shells.

But shortages of vital raw materials - particularly cotton, camphor, pyrites and saltpetre - meant it could not expand its production at the same rate, and only 8.9 million shells were made in 1915.

The following year saw a huge improvement, thanks to efforts of the KRA, the wartime raw materials department, which commandeered stockpiles, allocated distribution and, most importantly, oversaw the chemical industry's production of synthetic substitutes.

In 1916, as a result, the production of German shells increased almost fourfold to 36 million. But in the long term, the Central Powers - Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria - could not hope to compete with the Allies' financial and industrial muscle.

The former's total war expenditure of $61.5bn was less than half the latter's $147bn.

In the summer of 1916, Germany instituted the poorly thought-out and ineptly administered Hindenburg Programme - named after the army commander Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg - in an attempt to boost its production of weapons.

Instead it drained the army of a million men, brought on a major transport crisis and intensified the shortage of coal.

In early 1917, Germany tried to protect its depleted and under-equipped forces on the Western Front by withdrawing to the fortified Hindenburg Line, and by launching unrestricted submarine warfare.

The latter caused the US to enter the war, thus tipping the munitions balance even further in the Allies' favour. It was, ultimately, a war of attrition that the under-resourced Central Powers could not hope to win.

Ever since World War I, superior force is no longer measured in terms of men or horses, but in the means to wreak destruction.

In World War II, the Allies dropped 3.4 million tons of bombs across Europe and Asia. In Vietnam, an incredible seven million tons were dropped on Indo-China.

The manufacture of munitions played an even bigger role in World War II

The cost has also increased. In the second Gulf War, the US launched its wave of shock and awe against Iraq by firing 800 Tomahawk Cruise missiles over a period of just 48 hours.

Each one cost $0.5m. Today, a single Eurofighter Typhoon costs around £50m and the proposed Joint Strike Fighter is likely to come in at more than £100m each.

For entire campaigns, the scale of spending is staggering.

It is estimated that the war in Afghanistan has already cost the British taxpayer £18bn. And yet for all the sophistication of its military equipment, Nato's victory over an opponent armed with little more than Kalashnikovs and homemade bombs is far from certain.

Having the best weapons is usually decisive, but not always.

Saul David is Professor of War Studies at the University of Buckingham

His series Bullets, Boots and Bandages: How to Really Win at War is broadcast on BBC Four at 21:00 GMT on Thursdays 2, 9 and 16 February 2012. Catch up on earlier programmes via BBC iPlayer (UK only) at the above link.