Titanic: The final messages from a stricken ship

- Published

The Carpathia was one of the ships that received the Titanic's calls for help

On the night the Titanic struck an iceberg, a network of wireless operators on ships and land stations frantically communicated with each other across the expanses of the North Atlantic in an effort to mount a rescue mission. The surviving messages form a real-time record of the events of that night.

The story of the Titanic is barnacled with myths and legends.

It has become part of the popular imagination, a symbol for the most epic and glamorous failure. It is tragedy with tea dances.

But there is really only one first-hand, real-time record of what happened that night - the collection of wireless messages sent between the Titanic and the other ships which hurriedly tried to organise a rescue operation, during that freezing night in April 1912.

It is a telegraphic narrative showing how the Titanic had been given warnings of ice by other ships - and which records the increasingly frantic calls for assistance after the collision with the huge iceberg.

And to mark the Titanic's centenary, the BBC World Service's <link> <caption>Discovery programme</caption> <altText>Titanic - in her own words</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00q89fy" platform="highweb"/> </link> is broadcasting an unusual re-creation of these conversations.

Audio artist Susanne Weber has used speech synthesis software to translate these Morse messages into spoken words.

These are mechanical voices recreating the exchange of wireless messages, rather than actors performing a script, and it produces an eerie representation of how these overlapping messages crackled out over the airwaves.

It is something like hearing the urgent and confused text messages sent from a disaster.

Unlike in the Hollywood films of the tragedy, these wireless messages are stoically understated. Copied out in neat copperplate handwriting, and kept on the ships that had been in contact with Titanic, they are the actual words of the crew and passengers.

It's the Titanic in her own words.

Wireless was still a relatively young technology at the time of the Titanic's maiden voyage.

The Marconi company, the Edwardian equivalent of a top technology brand, had put its wireless operators on board some of the more prestigious ships.

The Titanic, as the showcase of an ambitious, optimistic era, had the biggest and best wireless equipment in the world.

It was still something of a novelty and much of the initial wireless traffic was from first class passengers sending messages to their friends, rather like text messages showing off about a glamourous trip.

Italian electrical engineer Guglielmo Marconi's equipment was on board many prestigious ships

"Hello Boy. Dining with you tonight in spirit, heart with you always. Best love, Girl," read one message sent on to New York, the Titanic's intended destination.

A message sent on to Los Angeles said: "No sickness. All well. Notify all interested in poker."

"Fine voyage, fine ship," wrote another, unaware of the awful irony of how that might later sound.

The wireless operators sending these messages were independent young men of the modern age, who had been recruited with the promise of escaping "blind alley careers".

They chatted to wireless operators in other ships in a jaunty, mock public school slang, calling each other "old man".

As well as letting passengers send personal messages, they provided the first wireless news service for ships.

As the Titanic crossed the Atlantic, the news headlines were about industrial unrest on the railways and a high-profile murder in France.

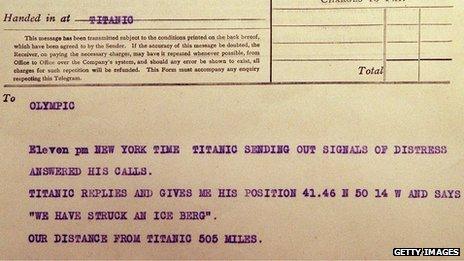

A message from the Olympic reports that it has received word from the Titanic

But the wireless was also beginning to be used for more serious purposes.

Ships gave each other safety information - and the Titanic received detailed advice about the location of icebergs - or "bergs, growlers and field ice" as one ship's captain described them.

Investigations after the sinking would never satisfactorily establish why these warnings had been ignored.

The senior wireless operator, Jack Phillips, had still been sending passengers' messages when the ship struck an iceberg. The collision was described as sounding like the tearing of calico.

With only enough room in the lifeboats for half the passengers and crew, the Titanic's captain turned to his only lifeline - the wireless - and asked the two Marconi operators to call for assistance.

The distress signal used by Marconi operators - CQD - boomed out over the Atlantic. The wireless operators joked they may as well also try another new distress signal that had been introduced - SOS - because they might never get a chance to use it again.

While the lifeboats were lowered, with awful goodbyes between husbands, wives and children, the wireless operators stuck to their task.

"Come at once. We have struck a berg. It's a CQD, old man," the Titanic called to another ship, the Carpathia.

"We have struck an iceberg and sinking by the head," she told a German ship, the Frankfurt.

The Titanic's messages caused consternation and disbelief among other ships.

They called back to the Titanic struggling to grasp what was happening, then urgently forwarded the distress signals in the hope that someone would be near enough to help.

It was like trying to organise a rescue by Twitter, with operators trying to make sense of the stream of sometimes contradictory information.

"We are putting passengers off in small boats. Women and children in boats. Cannot last much longer. Losing power," said the Titanic as the situation grew ever more desperate.

"This is Titanic. CQD. Engine room flooded."

The Titanic's captain Edward Smith gave the orders for the distress signals to be sent out

In response her sister ship, the Olympic called back: "Am lighting up all boilers as fast as we can."

There were also flashes of anger in the confusion. "You fool... keep out," the Titanic barked at a ship almost 200 miles away who had interrupted to inquire: "What is the matter with you?"

The last recorded messages are increasingly desperate and fragmented - although a shore station officer following the exchanges reported there was "never a tremor" in the Morse tapped out by Jack Phillips.

"Come quick. Engine room nearly full," was sent from the Titanic only a few short minutes before the ship finally sank.

When the Titanic fell silent, the chasing ships carried on calling out for news, co-ordinating the rescue of the survivors.

And the wireless became the only way for survivors to contact their families.

"Meet me dock with two hundred dollars, underwear, cap, big coat - am well but slightly frozen," messaged one survivor from the Carpathia rescue ship.

"Completely destitute, no clothes," said one another. Words cost money - and a masterpiece of brevity reported: "Safe, Bert."

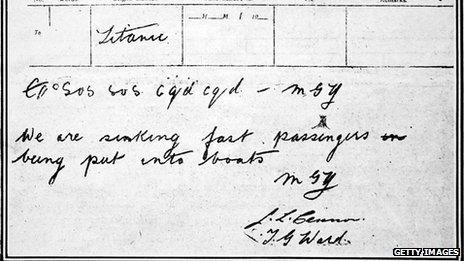

One of the messages sent by Jack Phillips says the ship is 'sinking fast'

These poignant, first-hand reactions to the disaster had been gathered in an archive by John Booth, a Titanic historian and expert on old prints. But many were sold off at auction in the early 1990s.

Jack Phillips did not survive the sinking. But his heroism, staying at his post after being released from his duty by the captain, became an enduring part of the Titanic story.

Not least because one of the most influential templates for all future Titanic stories came from Harold Bride, his junior wireless operator.

Bride survived on an upturned lifeboat and then sold his story to the New York Times.

His story was a global media sensation, setting the tone of heroic self sacrifice, with the first accounts of the band playing while the ship sank, with tales of selflessness and cowardice.

And he commemorated the role of Jack Phillips, unflinching, even when he knew better than anyone else that there was no chance of a rescue ship arriving in time.

"I will never live to forget the work of Phillips during the last awful 15 minutes," said Bride.

"I suddenly felt a great reverence to see him standing there sticking to his work while everybody else was raging about."