Why does the 1970s get painted as such a bad decade?

- Published

Of all post-war decades, the 1970s has undoubtedly had the worst press, but the truth is that most ordinary families in 1970s Britain were better off than ever, writes historian Dominic Sandbrook.

The 1950s are symbolised by the television and the washing machine, which transformed the lives of so many families.

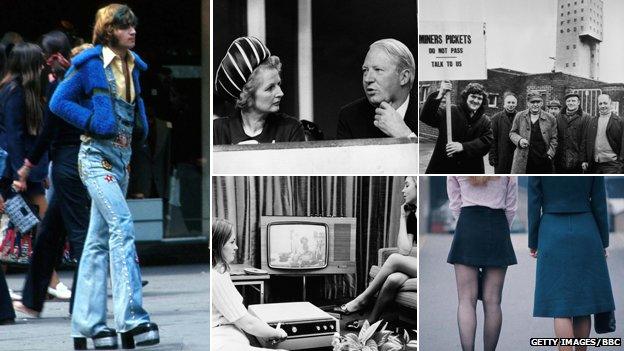

We misremember the 1960s as the decade of the Mini, which was actually invented in 1959, the mini-skirt, which surprisingly few women actually wore, and the Pill, which most women never took. We remember the 1980s as the decade of gigantic hair, shoulder-pads, the Filofax and the home computer.

But in the popular imagination the 1970s are the poor relations, to be lampooned and despised - the era of Edward Heath, the decade of the donkey jacket, the age of the Austin Allegro.

When they flash up on our screens, we see lurid wallpaper, silly hairstyles and burly men warming their hands around braziers. Who would ever want to commemorate all that?

In many ways this habit of giving decades different historical personalities is a bit of a gimmick, a quirk of the calendar, that distorts the way we remember the recent past.

Look at any photograph from the mid-1970s, and you can often see people wearing clothes that would have been at the cutting edge of fashion in 1958.

Footage of picket-line confrontations often shows strikers wearing suits and ties, as though dressing for a family wedding.

The teenagers dancing on Top of the Pops are usually wearing yesterday's fashions, topped off with a pair of National Health glasses.

Even the burly policemen standing protectively around Margaret Thatcher as she walked into Downing Street in May 1979, with their luxuriant moustaches and thick sideburns, looked as though they had been transported 10 years forward in time.

But like so many stereotypes, the cliches of the grim 1970s have more than a grain of truth. These were desperately difficult years for Britain, both politically and economically.

In many ways they marked a reckoning for a country that had been too complacent for too long, basking in the sunshine of post-war affluence, and indifferent to the fact that our foreign competitors had not only caught up with us - they were leaving us behind.

In 1970, the self-made builder's son Edward Heath came to power promising a "quiet revolution" that would turn around the fortunes of Great Britain PLC.

Sailor Ted, however, soon ran aground, his ship scuppered by the lethal combination of an energy crisis, a financial crash and a second miners' strike in two years.

And though Labour's Harold Wilson got the country back to work, it came at the price of inflation at almost 30% and a humiliating bailout from the IMF.

Perhaps fittingly, the decade ended with another prime minister being humiliated by the unions in the Winter of Discontent, though this time the victim was the veteran Labour bruiser Jim Callaghan.

Perhaps never before had the political establishment seemed so impotent and irrelevant - little wonder, then, that for the first time in years, emigrants actually outnumbered immigrants.

Space hoppers became the toy of choice for many children in the early 1970s

Even Callaghan himself seemed to have little faith in his native land. "Our place in the world is shrinking: our economic comparisons grow worse, long-term political influence depends on economic strength - and that is running out," he told his colleagues in November 1974. "If I were a young man, I should emigrate."

And yet the strange thing about the 1970s is that although many people vividly remember the power cuts, strikes and shocking headlines, they often have surprisingly affectionate personal memories of the decade that taste forgot.

It has become a cliche to look back through rose-tinted glasses at the world of Bagpuss, space hoppers and Curly Wurlies - all of which, I should admit, dominate my memories of the decade, because I was born in 1974.

But in a funny way, those things actually work very well as symbols of the decade, because what they represent is the reality of everyday affluence.

The fact that so many children had space hoppers, ludicrous as it may seem, is testament to the fact that even working-class families now had a solid disposable income and could afford toys for their younger members.

Even Star Wars, which first went on general release in Britain in early 1978, would never have become such a phenomenon had not so many children had the pocket money for all those Palitoy figures.

The truth is that behind all those terrible economic and political headlines, most ordinary families in 1970s Britain were better off than ever.

While people shook their heads sorrowfully over the breakfast table, digesting the news of some new IRA bombing or absurdly petty British Leyland strike, their surroundings often told a rather more optimistic story.

The lurid furnishings of their new suburban homes, the swanky hostess trolley in the kitchen, the bottles of Blue Nun and Black Tower cooling in the fridge, the brand new colour television in the lounge, the turmeric-coloured Rover SD1 in the drive, even their teenage children's painfully tight flared trousers - all of those things, which are so easy to satirise today, reflected the realities of a brave new world, forged in the crucible of mass abundance.

And although we often think of the 1970s as the end of something - the tired, miserable hangover after the long party of the Swinging Sixties - it makes much more sense to see them as the beginning of a new chapter in the story of modern Britain.

For most ordinary people, after all, the 1970s brought new experiences that their parents and grandparents could barely have imagined.

The most obvious example is the package holiday abroad, which 30 years earlier would have seemed like something from science fiction.

In 1971, British tourists took some four million holidays abroad - which then seemed an awful lot. But by 1973 that figure had jumped to nine million and by 1981 it was more than 13 million.

For even relatively poor, working-class families, holidays no longer meant Blackpool and Bognor but Malta and Majorca. And "abroad", once regarded with such suspicion, now meant two weeks of sun, sea, sand and sangria.

The boom in foreign holidays was only one example of a nation broadening its horizons. Yes, the TV schedules were still full of casual sexism and astonishing racism, while teenage boys who wore make-up in emulation of Marc Bolan and David Bowie often risked a vigorous kicking.

David Bowie re-emerged in 1972 as the flamboyant and androgynous Ziggy Stardust

But from professional working women to long-haired footballers, from pornography in the corner shop to computers in the office, the cultural texture of British life probably changed more quickly between 1970 and 1980 than during any other post-war decade.

As late as 1971, women were banned from going into Wimpy Bars on their own, after midnight, on the grounds that the only women out on their own at that hour must be prostitutes.

Yet only eight years after that rule was lifted, Margaret Thatcher was walking into Downing Street as Britain's first woman Prime Minister. There could hardly be a better symbol of change.

Of course Mrs Thatcher's election victory is often seen as the decisive watershed in our recent history - the moment when everything was radically transformed, for good or ill. But Mrs Thatcher won in 1979 not just because she offered something different, but because she understood how much Britain had changed already.

As a working woman distrusted by the traditionalists, she was a fitting representative of the changes that had remade Britain in the previous 10 years.

She appealed to a new spirit of self-interested materialism - the same spirit that the Yorkshire miners' leader, Arthur Scargill, of all people, had captured as early as 1970, when he told an interviewer: "You only get as much as you are prepared to go out and take."

And she appealed to a new ethic of populist individualism - the same ethos of permanent self-reinvention that David Bowie had captured, when as the androgynous Ziggy Stardust, he told Britain's teenagers that "one isn't totally what one has been conditioned to think one is".

Thatcher, Scargill and Bowie. You could hardly imagine three stranger bedfellows - the grocer's daughter from Grantham, the Marxist miner from Barnsley, the gender-bending rock star from Bromley.

But in their different ways, they captured the complicated, contrary spirit of a decade that was richer, more interesting and a lot more important than most of us realise.

Dominic Sandbrook's series <link> <caption>The 70s</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01glsyl" platform="highweb"/> </link> is broadcast on BBC Two at 21:00 BST on Mondays 16, 23 and 30 April and 7 May 2012. Catch up via BBC iPlayer (UK only) at the above link.