Cabaret and football: Life before death in the Holocaust

- Published

Songs composed and performed by Jews confined in a Nazi ghetto during the Holocaust have been pieced together by researchers and can now be heard again - a distant echo of the daily lives of men and women who would one day, if not immediately, be sent to their death.

In a hushed studio theatre in the heart of Tel Aviv, the ghosts of the Holocaust are singing again.

A small group of performers has been recreating songs written in the ghetto of Theresienstadt - the prison community near Prague where the Nazi authorities gathered Jewish families from Czechoslovakia and beyond between 1941 and 1945.

Composers and songwriters like Viktor Ullman and Karel Schwenk were among the prisoners and they left an extraordinary testament to the durability of the human spirit as they waited at the gateway to oblivion.

Terezin March from Cabaret Terezin

Around 160,000 Jews passed through the ghetto in its four years of operation - 36,000 died there of malnutrition, mistreatment and disease. Of the 90,000 men, women and children who were sent east to death camps like Auschwitz only 4,000 returned.

But the music of Theresienstadt doesn't sound or feel like a requiem for the dead - much of it was written in the cabaret style popular in Central Europe between the wars.

It has a spiky, sarcastic feel to it - shot through with sudden shafts of sentimentality.

Ullman and Schwenk, together with the other artistes, perished in the Holocaust and it took an extraordinary piece of musical archaeology to bring their songs back from the dead.

"Five years ago, we interviewed 20 survivors from Theresienstadt," explains Professor Michael Wolpe, the musicologist behind the project.

"Each one of them sat down and sang us songs from the cabaret, and there were a few who even play the piano a bit. As I understand from the survivors, [the music] is absolutely like it was then."

Rediscovering the music of Theresienstadt (known as Terezin in Czech) provides a sharp reminder that while most of us have a clear picture of the outline story of the Holocaust, relatively little is known about how daily life was lived within it.

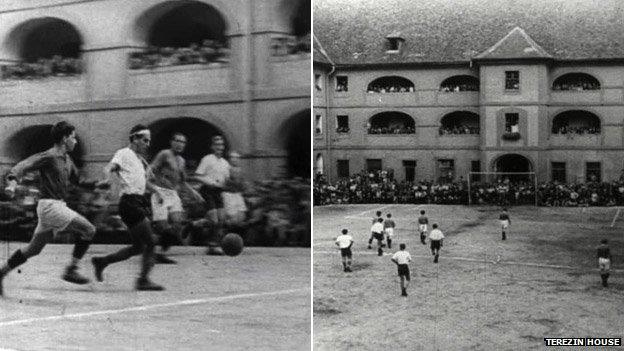

New exhibitions in Israel of photographs of football matches played inside the ghetto underline that perception.

Games were played in front of substantial crowds with some spectators looking down on the seven-a-side matches from balconies high above the courtyard that served as a pitch.

Search on the internet and you will easily find the unbearably poignant footage of the doomed players - most had been transported to the death camps within weeks or months of the film being shot.

One of the few who survived was Peter Erben - now 91 and living in the Israeli Mediterranean city of Ashkelon with his wife Eva, who also lived through the nightmare of Theresienstadt.

Peter Erben now, and (above left) wearing a white headband during a Thereseinstadt match

Peter's memories of the Holocaust are grimly compelling - he survived transportation to the death camp because he was moved to Theresienstadt late in the war, when the approach of the Soviet army was already disrupting the operation of the camps.

He survived a period in the slave labour camp at Mauthausen in Austria too, his personal story an extraordinary odyssey of good luck woven into a tapestry of despair and depravity.

Of his days playing football in Theresienstadt as he waited through the long months for the inevitable transfer to Auschwitz he says simply: "Football was very important in Theresienstadt - there was a game every week and thousands of people came. Even the SS men were there in civilian clothes. They liked it too."

We have grown used to the over-arching narrative of the Holocaust with all its cruel destruction - but we know little of its grim subtleties, and perhaps struggle to find the words to describe them.

The truth is that Theresienstadt was a place of death but it was less brutal than the ghettos of Poland or Lithuania. It's not clear exactly how that came about - it may have been determined by the character of local commanders, or it may have been that the Germans drew ethnic distinctions between Jews from Central Europe and Jews from countries to the East.

The Czech ghetto was still a gateway to hell but because it was less brutal and squalid than the others it also came to play a role in one of the most extraordinary of all the German propaganda operations of World War II.

In an attempt to disguise the true nature of the Holocaust, the Nazi authorities consented to a request from the Danish Royal Family to allow a visit by Red Cross inspectors.

The results were a shameful farce - the inspectors seem to have agreed to speak only to the guards and commanders and not the malnourished inmates who were ordered to sit around in fake cafes drinking water dyed black so that it resembled coffee. Peter was one of those inmates.

The Germans even shot a propaganda movie, although they lost the war before they had a chance to show it around Europe.

Piano Introduction from Cabaret Terezin

Oded Breda, director of the Terezin House - a museum set up by survivors to commemorate and study the ghetto - says the film remains a powerful piece of propaganda for Nazi apologists and Holocaust deniers to this day.

"That film is still working. Look at it on YouTube and look at the comments that are left. People are saying, 'Look at Jews during the war, how they even played football. There was nothing [sinister].'"

If Oded Breda is right to claim that Holocaust-deniers are still reinforcing their grotesque perversions of historical fact with Nazi propaganda films then there are worrying signs for the future.

It is a good moment perhaps to pause and listen to the ghostly voices of the musical past in Theresienstadt, and remember the truth.