Studio 54: 'The best party of your life'

- Published

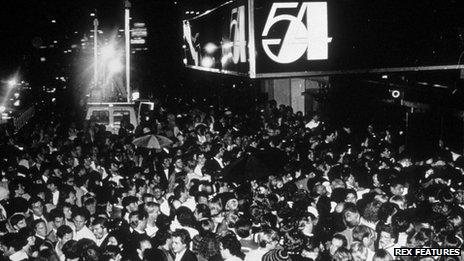

Most would-be clubbers never got past the doormen at Studio 54 who were looking for the right mix of people - especially those with high energy

It's 35 years since Studio 54 opened in New York. It quickly became the best known nightclub in America, riding the wave of 1970s dance music and newly found personal freedom. It made vast amounts of money for its two young owners. But after three years the party came crashing to a halt.

"On a good night Studio 54 was the best party of your life," says Anthony Haden-Guest, who reported on the club as a journalist throughout its short existence.

He says Studio 54 was the right club in the right city at the right time.

"Everything was happening at the same moment: there was the woman's movement, the gay movement, ethnic movements of all kinds. The whole place was combustible with energy."

Studio 54 opened just off Broadway in April 1977. The building had originally been a theatre and later a CBS studio.

Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager already had a club in Queens called Enchanted Garden. But 1977 was the year of Saturday Night Fever and disco reigned supreme. The young men were certain that what worked in an outer borough of New York could work in central Manhattan too.

Celebrities by the dozen flocked to Studio 54 and long lines of would-be clubbers queued outside hoping to be admitted.

"There was always a ton of people outside waiting to get in - people from all walks of life," says Myra Scheer, an early fan who later became Rubell's assistant.

Corridor of joy

"Most never got in, but if you caught the eye of Steve or of (doorman) Marc Benecke suddenly a path opened up.

Studio 54 regulars: Liza Minelli, Andy Warhol, Bianca Jagger, Halston

"Beyond the velvet rope was what I used to call the Corridor of Joy. It had ornate chandeliers and everybody there was screaming with joy that they got in. You could hear the pulsating music as you walked through and then you turned left and there was this dance floor. Everybody on that floor had the energy of being a radiant star."

Benecke can still recall how desperate people were to enter the club. "At one point you could buy maps which claimed to show how to get in through tunnels up from the subway system. It was crazy."

"Naturally people tried good old-fashioned bribery but that didn't work. Then I'd say to them they should go and buy the exact same jacket I was wearing - forgive me but I was only a teen at the time. And they'd go to Bloomingdale's and buy it and still they wouldn't get in."

"But if you were just dressing up in costume to get through the door, it showed you probably weren't the right person. We were looking for people with high energy," he says.

Looking great did not guarantee entry. "What we really wanted was the mix."

<bold>Rubber room</bold>

Haden-Guest says owner Steve Rubell had a sense for who ought to be on the dance floor on a specific night. "Every time was different. It was like a salad bowl - they might let in some straight-looking kids from Harvard, but then they'd also want a bunch of drag queens or whatever. Often it was surprisingly relaxed."

He said it would be impossible to run the club's VIP room today when a photo taken on phone can be spread around the world in an instant.

But the VIPs were photographed and often. The list is long and included Calvin Klein, Truman Capote, Liza Minnelli, Robert Mapplethorpe, Elizabeth Taylor and Andy Warhol. Other regulars are perhaps more surprising: Benecke recalls the classical pianist Vladimir Horowitz turning up regularly with his wife Wanda. "He always wore ear-plugs. He hated the music but he loved watching the people."

Scheer recalls Andy Warhol saying the club was a dictatorship at the door but a democracy inside. "There was no A-List or B-List or C-List. We came after the pill arrived and before Aids had a name. Women were thriving in terms of their sexuality and it was also a great time to be gay. There was no stigma inside Studio 54."

The club soon had a reputation as a place where physical intimacy needn't be limited to the dance floor. Benecke insists the sexual free-for-all has been exaggerated.

"They had a place called the Rubber Room upstairs. You would go up there and sure there might be couples having sex - but only one or two."

Haden-Guest was a regular visitor to what some assumed was a non-stop Bacchanalia of sex and drugs. But he thinks the amount of drugs taken has been overstated. "I had a wonderful time in disco culture but drugs played an extremely minor part. I think most people were just there to dance and have a good time."

Undeclared cash

The club's sudden end had less to do with public morality than with the fact that huge amounts of cash had gone undeclared for tax purposes. In 1980 Rubell and Schrager were sentenced to jail.

Attempts were made to revive the Studio 54 brand but the party was over. Steve Rubell died in 1989 and today, at 65, Ian Schrager is a successful hotel owner.

Looking back, Benecke wonders if the club's heyday had already passed when it closed. "The tax problems certainly speeded up the demise. But as a society we were changing into Punk and New Wave right after that. So Studio 54 would have had to change a lot to carry on at the same level of success."

Last year Studio 54 Radio launched on satellite in the US. It plays the hits of the disco era and Benecke and Scheer have a show discussing the old days.

"It's like we have Class of 54 Reunions," says Scheer. "Because we went to the coolest high school. Modern kids spend so much time texting or tweeting or getting on YouTube. But we were in the moment. We were really there."

<italic>Vincent Dowd's programme about Studio 54 is featured on the </italic> <link> <caption>BBC World Service </caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic>history programme </italic> <link> <caption>Witness</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p004t1hd" platform="highweb"/> </link> .