Early-onset Alzheimer's strikes families fast and ferociously

- Published

- comments

Mike Henley surrounded by his family

Alzheimer's is thought of as a disease of the elderly. But the early-onset form of the disease can wreak havoc for young people and their families.

On a fall day in Westbury, New York state, Brandon Henley, 18, hastily opens the front door of his small house. The nurse his mother has been calling all day has finally arrived to deliver urgently needed anti-seizure medicine.

Behind him, she notices on a recliner a frail man, eyes closed, under many blankets.

"Is that your grandfather?" she asks.

"No, it's my father," says Henley.

Mike Henley is 47. What hair he has left is white. He no longer has teeth and is so thin and pale that it seems he could vanish at any moment. He cannot speak, he cannot walk and no-one knows if he can understand what is going on around him.

Mike Henley has Alzheimer's disease.

'What about the kids?'

When he was diagnosed at 36, doctors said he would die within five to seven years. More than a decade later he survives. "Younger people's bodies are stronger," says his wife, Karen.

But young-onset Alzheimer's also progresses faster than the disease in older people. Mike was diagnosed in 2001. By 2004 he was unable to speak and by 2006 he was unable to walk.

An estimated 5.4 million Americans have Alzheimer's. Early-onset Alzheimer's disease, commonly known as young-onset Alzheimer's disease, afflicts people under 65 and accounts for less than 10% of cases of the disease.

In the UK, the Alzheimer's Society provides statistics on all forms of dementia, noting that Alzheimer's accounts for the majority of these cases. They count 800,000 people with dementia in the UK, including more than 17,000 younger people.

It is a small proportion, but an extremely aggressive form of the disease. The impact on patients and families is typically severe.

Once diagnosed with Alzheimer's, younger people have scant time to organise their future. They face a lot of legal work: coping with insurers, arranging for Social Security and power of attorney.

Mike's first question, when he learned he had Alzheimer's, was "What are we going to do about the kids?" At the time, Courtney was nine years old and Brandon eight.

At first Mike and Karen decided not to tell them anything, "but they were already questioning why he wasn't working anymore", recalls Karen.

"I remember asking if mom and dad were going to get a divorce," says Courtney. "I kind of picked up on a difference to how things normally were going. That was the only thing that I knew could be wrong."

With the help of a child psychologist, Karen started to explain to her children that their father had an illness affecting his brain. She said that he might say or do things that he wouldn't have before.

"It was one of the toughest days we ever had, one of the toughest things we ever talked about," Karen says, quietly. Her son started to sob. "He asked if his dad was going to die. He was only seven."

"How is it going, Daddy-o?" asks Courtney Henley. An aide is feeding her father his dinner. He gives no reply, no reaction. She continues speaking to him nonetheless.

"I don't like when people talk to him like a baby, because he's not a baby and if he can understand, it's not going to help his self-confidence, it's going to make him feel worse," she says.

Courtney, a college student with a joie de vivre that defies her grim situation, sounds a lot more positive about her dad's abilities than his vegetative state would suggest.

The Henley family in 2002

"He definitely knows if it's me, my mom and my brother, or one of his regular aides as opposed to a complete stranger," says Henley. "He doesn't eat well, or as well, with people he doesn't know."

All the Henleys have become caregivers for Mike, bolstered by the aides who come to their house every day since he entered hospice care.

"He's incontinent so he has a diaper on, so that has to be changed," says Courtney. "The aide does that in the morning. We do that at night."

This winter evening, Courtney is preparing to go to a friend's birthday party. But instead of primping and trying on outfits, she has to help her mother and brother put her dad to bed - a complicated manoeuvre. Mike has become very fragile and has developed painful bedsores on his back and hips.

With the help of two large bands of fabric placed under Mike's back and legs, Brandon and Courtney struggle to lift him from his chair.

Then Karen starts Mike's night-time treatments: she changes his clothes, massages his emaciated hands with cream, installs his nasal breathing tubes.

When all that is finished, she settles Scruffy, Mike's protective teddy dog, over his blankets.

Throughout, Brandon lies next to his dad playing games on his new iPhone.

Role reversal

To most adults, let alone children, the situations the Henleys face every day would be hard to bear. That it often affects families with young children is just one of the distinguishing factors of young-onset Alzheimer's.

Little is known about the needs of children in early-onset families. But these children are going through a profound role reversal, which can lead to confusion and fear.

"It makes them feel that it's something they're doing, that it's their fault," says Caroline Rosenthal Gelman, associate professor at Hunter College in New York. These children have to deal with both the disease and the anxiety and distress it causes their other parent.

"It's a loss of both parents, in a way," she says.

Not everyone seems to cope as well as Courtney and Brandon Henley.

Leo Dzwil, diagnosed with young-onset Alzheimer's four years ago at 51 is the father of two teenagers.

At the time, son Michael "pretended that everything was the same", says Leo's wife Corrine, but had uncharacteristic behavioural problems. Eventually Michael recovered, though his dad didn't.

Today, Leo Dzwil lives in a nursing home on Long Island. He no longer walks and barely talks. He sits in a chair all day, with his eyes almost always closed.

"It's very, very hard to see," Corrine says quietly. "My son, he went in July and said 'I'm not doing this anymore.' And he hasn't." Corrine's daughter, Lauren, now 23, went in November and decided that was the last time.

"It's not that I don't care," says Lauren, "I just care too much."

Children who witness a parent struggling with Alzheimer's also have to confront the daunting fact that they too may be stricken at an early age.

The young-onset forms of Alzheimer's disease have hereditary factors in 15-20% of the cases, says neurologist Yves Agid.

Mike Henley's case is one of those: his mother died of young-onset Alzheimer's. So did one of his brothers. The other brother is fine, so far. Because Mike has a the genetic mutation that leads to young-onset Alzheimer's, there is a 50-50 chance that Mike's children could have it too.

"I don't really think about it too much," says Courtney, calmly stroking her father's hand. She has declined to be tested.

If her mother had known Mike carried the familial gene when they married, they wouldn't have had children. That's also why Courtney doesn't want to know. "I don't want to have it impact my life decisions."

Sleepwalking brain

By the time he'd turned 51, Leo Dzwil could no longer figure out how to close a side table, something he had been doing for 20 years. His wife knew something was wrong.

Doctors diagnosed the problem as stress.

"I was told that I should have nice warm dinners for him when he came home," his wife says. It took another year and a different doctor to finally diagnose Leo with young-onset Alzheimer's disease.

Leo's brain was shrinking very fast: his brain activity when he was wide-awake was equivalent of that of a normal person asleep.

"Young people with Alzheimer's have a tremendously hard time getting a diagnosis," says Lauren Tiede, the early stages co-ordinator for the New York City chapter of the Alzheimer's Association.

"It takes probably a second, third, fourth opinion." Many of her young clients were at first diagnosed with chronic stress, overwork, depression, even schizophrenia, Tiede says.

Failure to get the right diagnosis, beyond emotional difficulty for young-onset families, also brings great financial distress.

Medicare, the US federal health insurance programme for people over 65 and some younger ones with disabilities, only takes effect a year after a person has been declared disabled.

Leo Dzwil enrolled in Medicare and received his first reimbursement only in December, though he'd lost all self-care ability more than a year earlier.

Even when diagnosed, young-onset patients can still be denied Social Security disability income, which requires a diagnosis proving they are incapable of working.

Administrators have a hard time believing that someone so young, with no apparent physical disability, can't even find a manual job, says Lauren Tiede of the Alzheimer's Association.

Young-onset Alzheimer's disease was only added in February 2011 to the Compassionate Allowance programme's list of medical conditions that always qualify for financial benefits.

Yet financial support is essential for the survival of families affected.

There is "no pension to fall back on. There's no retirement fund. There is no saved-up money," says Courtney Henley.

"Just imagine when you are 36," says Karen Henley. "You know, you really are just starting your life out, you are really just starting everything."

The Henleys went from living on two salaries to one. Karen still works as a legal assistant for a real estate attorney, but her income declined as the housing market fell.

Around the same time, Courtney and Brandon were looking for colleges. "That was pretty much how I determined where I was going to go: it was the place that was going to give me the most money," says Courtney, now majoring in film at Hofstra University, close to home.

'A giant toddler'

Corrine Dzwil's daughter, Lauren, wants to go to nursing school because of what's happened to her father. But Corrine can't help her pay tuition.

"I feel like a criminal!" Corrine says, indignant about having to explain all her expenses to Medicaid, the US federal and state insurance programme for people with low incomes.

"If I save anything for my daughter, they want to know why I'm gifting money."

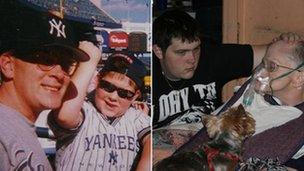

Mike and Brandon Henley before and after Alzheimer's

It was Leo who was the major breadwinner as a successful district manager at a grocery store. Today, all the money he receives from his early pension, Social Security and disability pays for his nursing home.

Corrine receives no compensation for the loss of the family's main income.

"I don't know how I'm going to retire," she says. "I don't want to be a burden to my kids down the line. The money they are taking was the money we were planning on retiring with."

While most young-onset families face extreme financial distress, states struggle to cope with a growing number of older patients.

As life expectancy increases, so do the number of people with neurological disorders: today, about one in eight Americans aged 65 and over has Alzheimer's, and nearly half of the people aged 85 and older.

Alzheimer's costs the US an annual $183bn (£117bn) and poses a critical challenge to Medicare.

Few states feel able to give patients and their families the financial help they need.

At the beginning of 2011, as Leo Dzwil's condition deteriorated rapidly, he became aggressive at times and incapable of taking care of himself or being alone at home. In his wife Corrine's words, he had become "a giant toddler".

Corrine, who had to continue working, made the decision to move him to managed care.

Despite the high costs, it can be difficult to find quality care. At first she was paying $5,000 a month.

"I'd go and he'd be filthy. Filthy. Not just a little dirty," remembers Corrine, tears filling her eyes.

After a few months she withdrew her husband and placed him in the nursing home where he lives today. Nursing homes tend to cost around $6,500 per month, and sometimes much more.

She feels guilty about placing her husband in a home. "I couldn't stand looking at how awful my husband looked after a while," says Corrine quietly. "I was depressed and I needed to just get away from it."

Lives forever changed

The Henleys decided otherwise. With Mike moved into the communal rooms, his family had to constantly live with Alzheimer's disease.

They also have to accept the healthcare worker who comes every day. "It was almost like we had some strange guest over all the time and we had to be very nice," says Courtney.

"Before Mike's illness, and even with two young children, I always kept a neat home," Karen wrote in an email.

"Now, I don't have the time or money to put into keeping it neat. I am a proud person and I do get embarrassed about the way my home looks."

Piles of laundry engulfed the kitchen; boxes and clothes blocked the stairs.

The tiny playroom became Mike and Karen's bedroom, and a hospital bed where Mike took his afternoon naps occupied the living room. Objects once stored in these rooms migrated to the dining room.

But after years of adjusting, the family now must confront yet another massive change: in February, Mike passed away, 11 years after his diagnosis.

"Caring for Mike had been our life... and half the kids' life," says Karen in an email. "Now that he's gone, there is a huge void and it will be quite some time before we find a new normal."

Courtney Henley has spent more than half of her life dealing with her father's Alzheimer's

Mike's brain was given to Alzheimer's research, just as he had requested.

At a nursing home in Long Island, Corrine Dzwil knows where to find her husband.

She walks past old people sitting in the corridor, looking lost. Leo is sitting in a chair in front of a television, with three other patients, including one moaning incessantly.

None of them are paying attention to the screen. "Hello Leo," says Corrine affectionately.

His eyes are closed and his head bowed, but he seems awake. Corrine starts gently stroking his neatly combed white hair, silently, looking at him tenderly.

Though he's now lost a lot of weight, has swollen hands and looks much older than his 55 years, you can still see a glimpse of the charismatic man Corinne remembers fondly.

Twenty minutes after arriving at the nursing home, Corrine says goodbye to her husband. No reaction.

Tears start filling her eyes. "It's like that every time," she says with sad resignation. "There's no point."

Still, she comes back every week.

<italic>Celeste Owen-Jones is a French-British journalist who lives in New</italic> <italic>York. She can be</italic> <italic>reached at celesteoj@gmail.com and on </italic> <italic>T</italic> <italic>witter</italic> <italic> at </italic> <italic>@</italic> <link> <caption>CelesteOJ</caption> <url href="http://twitter.com/#!/CelesteOJ" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic>.</italic>

- Published26 April 2012

- Published15 May 2012