A Point of View: Don’t mention the war?

- Published

It's time to stop invoking Hitler and the Nazis in arguments about everything from censorship to birth control - but we should never stop heeding the lessons of World War II, says Adam Gopnik.

Over the past few weeks, I have been talking about <link> <caption>bees</caption> <altText>PoV</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18279345" platform="highweb"/> </link> , and <link> <caption>the Beatles</caption> <altText>PoV</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18449107" platform="highweb"/> </link> , and babies (at least <link> <caption>ones who are babies no longer</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18367053" platform="highweb"/> </link> ), and also about <link> <caption>books and bad reviews</caption> <altText>PoV</altText> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-18549694" platform="highweb"/> </link> . I am as deep in the Bs as the crew that went hunting for the Snark in Lewis Carroll.

I hope you will forgive me if I turn this week to something, if not more serious, then more obviously sombre, and that is the question of what the memory of World War II ought to mean to people now.

It recedes, its soldiers die, its battles become the occasion for camp fantasy, or Quentin Tarantino movies - the same thing.

Recently, the Economist published a <link> <caption>long book review asking just that</caption> <altText>Economist</altText> <url href="http://www.economist.com/node/21556542" platform="highweb"/> </link> ; what WWII ought to mean to people now?

We know already what it means to publishers and television networks. The publishers love new books about the war's battles, and the cable shows can never get enough Nazis. A German friend once complained to me that educated Westerners often know far more about the German government during those five years of war than they do about all German governments in the 60 years of subsequent peace.

But then, as The Economist wrote: "The sheer magnitude of the human tragedy of [WWII] puts it in a class of its own, and its relative closeness to the present day makes claims on the collective memory that more remote horrors cannot."

Does it, should it, make such claims? Of course, there is a band of American neo-conservatives who insist on seeing every new year as another 1938, with whomever is the monster of the week cast as a Hitler figure.

On the other extreme, there are those who insist that there is, in a sense, nothing to learn from what happened then, because it was so uniquely, horribly evil. There is even a principle, frequently repeated during internet squabbles, and half-jokingly called Godwin's Law (after Mike Godwin, an expert in internet law of the unjoking kind, who first invoked it). It states simply that as an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler gets greater. The stupider the argument becomes, the more likely someone is to use the <italic>"reductio ad Hitlerium"</italic>.

Therefore Godwin's law implies - and this is the law-like bit - one should try never to compare anything or anyone current to Nazis, Nazism - or for that matter, to mention 1938, Munich, appeasement or any of the rest of the arsenal of exhausted exemplars. It's a bit like Basil Fawlty's old rule when the German guests come to the hotel: "Whatever you do, don't mention the war!"

And, to an extent, this caution is sane and sound.

Any resemblance is coincidental

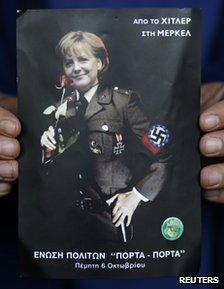

The people on the right who invoke "liberal fascism" should be bundled off - with those on the left, who morph Thatcher's or Blair's picture into Himmler's - shut up in a library, and made to read some history.

But I'm always haunted by the simple words of the historian Richard Evans towards the end of his good book, The Third Reich at War, where he said that we should always remember that what happened was not some act of Satan - though Satanic acts took place - but the result of the unleashed power of long latent traditions of militarism, nationalism and the hatred of difference. It was the force of three ever-living things, braided together like hissing, poisonous snakes around a healthy tree.

The danger is that each of these things is not necessarily evil on first appearance, and each seeks a new name in new times.

The old distinction between patriotism and nationalism, made many times by many people, has never been more vital to our mental health than it is now - as vital for the health of the country as the distinction between sexual fantasy and pornography is for the health of a marriage. Patriotism, like fantasy, is a kind of sauce, a pleasing irrationalism that is part of what makes us human - and saucy. Nationalism, like pornography, is a kind of narcissistic addiction that devours our humanity.

Patriotism is a love of a place and of the people in a place. As GK Chesterton understood, it becomes more intense the smaller the unit gets, so that it was possible for him to feel more patriotism for Notting Hill than for Britain.

Nationalism is the opposite belief; that your place is better than everyone else's and that people who don't feel this way about it are somehow victimising you.

Recently in America, "exceptionalism" has become the new name for this illness. All nations are exceptional, but some are more exceptional than others, and America is the most exceptional of all. This sounds like a mordant joke, but it is actually what many people in the US believe, and want everyone else to believe, and routinely arraign President Obama for not believing in enough. (As it happens, for good or ill, he does.)

To believe this, it is necessary first of all to be exceptional in never having lived in any other place that thinks itself exceptional.

Any American lucky enough to grow up in Canada, as I did, which believes itself rightly to be exceptional among the world's nations in its ability to cover an entire continent in common values without the governments ever having once resorted to internal violence. Or else to have lived, as I also have been lucky enough to do, for many years in France, which believes itself to be exceptional among the countries of the world because… well, I haven't time to enumerate all those reasons, though they were nicely summed up in Noel Coward's remark, just after the death of General De Gaulle. Asked what De Gaulle might say to God, Coward said that that depended entirely on how good God's French was.

Exceptionalism, it seems, is the least exceptional thing on earth.

Just as nationalism is the opposite of patriotism, not its extension, so militarism is an emotion opposed to the universal urge to honour soldiers for their courage. Militarism is the belief that the military's mission is moral, or moralistic. That the army can be used to restore the honour of the nation, or to improve our morals, and that a failure to use it to right every imagined affront is a failure of nerve, rather than a counsel of good sense.

After 9/11, in the US we suffered from a plague of militarism of this kind, again mostly from sagging middle-aged writers who wanted to send someone else's kids to war so that the middle-aged men could feel more manly in the face of a national insult. Militarism is not the soldiers' faith that war can be conducted honourably, but the polemicist's belief that war confers honour.

Hatred of difference - notice I carefully did not say racial hatred, or religious hatred. Hitler hated Jews because of their religion, and because of their race, but he hated them above all because of their otherness.

When I read well-intentioned people talking about the impossibility of assimilating Muslims in my adopted country of France, for instance, I become frightened when I see that they are usually entirely unaware that they are repeating - often idea for idea and sometimes word for word - the themes of the anti-Semitic polemics that set off the Dreyfus affair a century ago. For those writers, too, believed not that Jews were eternally evil, but that Judaism was just too different, too foreign to France, and tied to violence against the nation and its heritage.

And indeed there were Jewish anarchists in Europe, as there are Muslim extremists now. But there was never a Jewish problem in France, any more than there is a Muslim problem now.

Someone's mentioned the war

This is a question in which after a half-millennium of religious warfare, the results are really all in. If we accept the Enlightenment values of tolerance, coexistence and mutual pursuit of material happiness, things in the long run work out. If we don't, they won't.

So, from now, when we evoke Godwin's Law, as we ought to, I would like to propose Gopnik's Amendment to it. We should never believe that people who differ from us about how we ought to spend public money want to commit genocide or end democracy, and we should stop ourselves from saying so, even in the pixelled heat of internet argument.

But when we see the three serpents of militarism, nationalism and hatred of difference we should never be afraid to call them out, loudly, by name, and remind ourselves and other people, even more loudly still, of exactly what they have made happen in the past.

We should never, in this sense, be afraid to mention the war. We should say, listen: you've heard all this before - but let me tell you again just what happened in the garden the last time someone let the snakes out. It is exactly the kind of lesson that history is supposed to be there to teach us.