Rui Chenggang: China's biggest business journalist

- Published

Rui Chenggang has eight million followers on social media sites and his latest book sold just under 200,000 copies in its first month on the shelves. What has made this Chinese journalist such a huge celebrity?

No sooner had Rui Chenggang stepped from the cool of the airport terminal into the heat of the parking lot than a young woman tapped him on the shoulder.

She held a copy of his latest book and a pen.

Rui obliged, scribbling on the first page, then stepped into a waiting black Mercedes.

The car took him to an event where he sat behind a line of security guards, arms locked to keep fans back, and signed 2,000 more copies of his book.

Rui Chenggang is a man who, in China at least, needs no introduction. On a good night, he says, his news programme on state television is watched by as many as 300 million people. He has eight million followers spread over various microblogging sites, including <link> <caption>Weibo</caption> <url href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/pda/2011/jul/15/weibo-twitter-china" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Rui Chenggang is greeted by fans in Shenzhen

And his publishers say his latest book, Something for Nothing, about China's place in the world, sold just under 200,000 copies in its first month on the shelves - an instant best-seller.

So when Rui talks about challenges to China's economy, people listen.

As a leading figure on state television, his views say a lot about the shape of official debate in China. They can also be read as those of an insider.

"We're not immune to the global slowdown," he says. "There's a sense that 30 years of explosive growth are coming to an end."

The Chinese economy is slowing. In March, the government lowered its target for growth to 7.5%, off the long-term average of 9.8%.

In May, the government responded by speeding up approval for new spending on infrastructure projects, state-owned steel plants and public housing.

In June, the People's Bank of China cut interest rates for the first time since 2008 to encourage lending - and spending.

"Chinese people are responding to their rising prosperity by saving ever larger sums of money," Rui said. "They don't spend like people do in the West. Today, Chinese people save more as a percentage of national GDP than they did in the 1980s."

The World Bank estimates that Chinese households save more than 50% their annual income. Americans, it says, save just over 10%.

Rui says changing this is key: "Getting Chinese consumers to spend more will help not only China but the rest of the world."

He says Chinese savings rates are a measure of people's insecurity. So long as the social safety net and the rule of law are weak, people will save to protect themselves and their families.

He's devoted a chapter in his book to the subject, the title of which he translates as, "Can I please have a little bit of security?".

"The assumption at the beginning of the opening up and reform was that becoming rich was a good thing and a glorious thing - that wealth promises happiness," he said.

"But as people are getting richer, they're finding accumulated wealth does not necessarily lead to greater happiness. And sometimes people are richer but are probably less happy and feel less secure. So it's a very big question mark in the hearts and minds of many Chinese people."

There is evidence to support his claim. <link> <caption>Gallup Polling</caption> <url href="http://www.gallup.com/home.aspx" platform="highweb"/> </link> has been asking Chinese people about their sense of personal well-being for 15 years - during which time China's overall wealth has exploded.

"We saw no change, no shift, no movement in peoples' rating of their personal lives," said Dr Tao Wu, Senior Research Director for Gallup in China.

"The trend line is really flat. And what we're really learning is, the economic growth of China over the last 15 years didn't really translate into more happiness and satisfaction among the people. That's something really troubling and really puzzling to us."

Rui Chenggang insists personal insecurity is at the core of this trend.

His enthusiasm to move beyond dry macro-economic analysis and engage in discussions of happiness and well-being may explain his celebrity, particularly among the young.

About 5,000 students at Anhui University screamed when he took the stage after his book signing - a greeting fit for a rockstar.

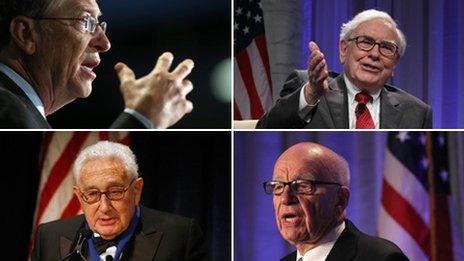

Rui Chenggang has rubbed shoulders with the likes of (from top left, clockwise) Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Rupert Murdoch and Henry Kissinger.

But there stood the business journalist, TV-anchor cool in manner and dress (a navy blazer and open-collared shirt). He offered advice for young people hoping to match his success, particularly on the world stage.

At 35, he's already a veteran of the annual Global Economic Forum in Davos.

He's been going every year since he was 22. His book is filled with photos of him with people such as Warren Buffett and Bill Gates. His private conversations contain references to them, too: "Rupert (Murdoch) told me... Henry (Kissinger) said..."

One student asked, in English, how to become so "international". Rui's answer was simple: Think for yourself. Ask questions. Read widely.

His performance was as skilled as any of the winning politicians he's met. He took students' questions seriously, made a few jokes, and even left the giant stage to walk among them with his microphone - which inspired some to clap, some to scream, and most to point the camera on their mobile phones his way.

Rui's critics - and he has them - will sometimes point to something else: a nationalistic streak. He successfully campaigned to have the US coffee giant Starbucks removed from the Forbidden City, arguing that a place of such national importance should instead use a Chinese firm.

He has asked on his microblog when Chinese leaders will start being chauffeured in Chinese luxury cars, rather than the ubiquitous foreign ones of today.

Starbucks was removed from the Forbidden City after protests

(He drives a Jaguar, built by India's Tata Motors, "because it is built by a company from a developing country".)

Another criticism, breathed mainly by those who only know him through the media, is that he is cocky.

On a panel with the US Ambassador to Beijing, Gary Locke, Rui asked if he flies economy class instead of business "because you owe us so much money?"

At a press conference with President Obama in 2009, <link> <caption>he said he could represent "all of Asia" with his question</caption> <url href="http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/evanosnos/2010/11/interpreting-obama-and-the-chinese-press.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> - a comment that still sends eyes rolling among journalists in Beijing.

All these incidents, Rui says, are more complicated than are often portrayed. And the reactions they've generated perhaps say as much about how the world sees a new, confident China.

Rui is patently not anti-foreign or anti-American. He studied at Yale University and still travels to the US frequently to meet senior American officials.

One of his closest friends is Kevin Rudd, a former Australian prime minister.

"The world has turned on its head," Mr Rudd said of China's economic transformation since 1978. "This is a new reality for the Chinese, getting used to that. And frankly, for the Europeans as well."

Rui is in some ways a face of that transformation. Despite the current slowdown, he is optimistic that China can change to meet new challenges.

"It's precisely because China has embraced institutional reform over the last 30 years that China is where it is today."

But Rui warns against triumphalism. "Yes, there are problems. The job is not done."

<italic>Rui Chenggang's two part documentary China - The Insider's View was broadcast on BBC World Service. </italic> <link> <caption>Listen back via iplayer</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00t7x2r" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic> or </italic> <link> <caption>download the podcast</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/docarchive" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic>. </italic>