Foster care: Meeting the boy who lived at 35 addresses

- Published

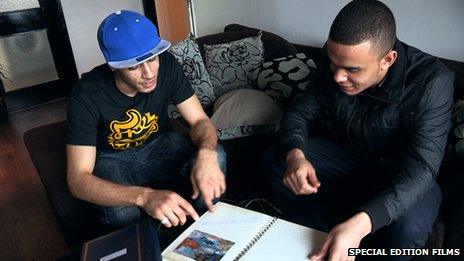

Ashley-John Baptiste (pictured) met one man who grew up in 35 different homes

X-Factor contestant Ashley John-Baptiste went from a tough childhood in care and foster homes to success at Cambridge. Here he tells his story and speaks to others who have been in care.

I was placed in care at the age of two and remained in the system until adulthood.

I had four different homes in that time, three different foster families and spent several years in a children's home.

I've always felt being moved around so much, often very suddenly, without any real explanation, can be really damaging to anyone growing up. But I think actually I was one of the lucky ones, especially after meeting Scott, who is roughly the same age as me.

"I've been in care since I was six months old. I've had 35 addresses," says 22-year-old Scott.

"Some places were pretty good but some were pretty bad. One set of foster carers used to send me and my brother away at Christmas because they said that was family time. So we never really felt like part of the family."

For many children in care the fear of being moved on, especially if they have challenging behaviour, is a recurring theme.

"Often my foster parents weren't resilient enough. They were like, 'this kid's a little git, let's move him on. There's thousands of other kids in care, we'll just get another one,'" Scott says.

It was one of many shocking things that I learned on my journey making a film for the BBC. The most horrible was finding out that two of the boys I lived with in a children's home are dead, and a third is in prison for a shooting.

Having made this film, I've come to realise how different my life could have been and how much I owe to the foster parents, like Fresia and Ervin, who opened up their home to me, gave me stability and encouraged me to achieve a place at Cambridge.

But even a successful foster mother like Fresia believes a rethink is required on foster parents.

"It should be viewed as a job. If they have more emphasis on the carers, you'll encourage more people.

"It's more than money, it's a vocation and if you're called to be a foster carer you do it wholeheartedly," she tells me.

The outcomes for children growing up in care are really not very good. A third of the UK's homeless population is from the care system and over a quarter of all prisoners grew up in care.

I met Jerome who grew up in care with his brother.

After eight years in one foster home, Jerome and his brother were split up. Jerome remained in a stable home while his brother was shunted around the system. His brother is now in prison.

"The more you move them the more you scar them, because it's like you're just letting me know people don't care about me," says 22-year-old Jerome.

"When you ask the kids what they want - they say simple things like I want my foster carer to give me a hug, or call me when I've had an exam.

"They're the simple things. And none of that costs money."

Jerome (left) was separated from his brother in the care system

Perhaps, most depressing of all is that half the people who grew up in care in the UK have children who are taken into care - which just perpetuates the cycle and confirms to me that the start you get in life is so important.

I truly believe that being moved around as much as some children are can cause long-term damage.

How can you be expected to move into adulthood as a productive member of society when you're so used to having the rug pulled from under you?

How can you complete your studies and do well in your exams if you're constantly on the move?

I met 18-year-old Sara, and helped her move from one hostel to another.

She hadn't been given any notice so all her possessions were in bin bags. In the back of taxi, surrounded by everything she owns, she tells me: "This is as good as life gets for me."

I went back to see her in her new place a couple of weeks later and even though it was tiny, like living in a shoe box, she's settled in well and has even managed to improve her attendance at college.

"I'll say to people you can't change your past, but you can change your future."

"I don't want to be in the system no more. I don't want to be in the care system. I don't want to be in no benefits system," Sara says.

She believes, like me, education offers an escape route.

"If I have a good education, I can obviously get a good job."

Not everyone can be as strong as her and who knows how she'll keep motivated if forced to move again?

Sara's frequent moves are partly because of problems in the system.

The Fostering Network has described a "crisis" in fostering because of an overall shortage of investment in the system and other issues.

"The foster care system is bursting at the seams," Vicky Swain of the Fostering Network tells me.

Earlier this month, <link> <caption>the government announced the Fostering for Adoption plan</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-18724999" platform="highweb"/> </link> designed to streamline the process of placing children in care with their eventual adopters.

It's a positive move and I welcome anything that gives children a sense of permanence and stability.

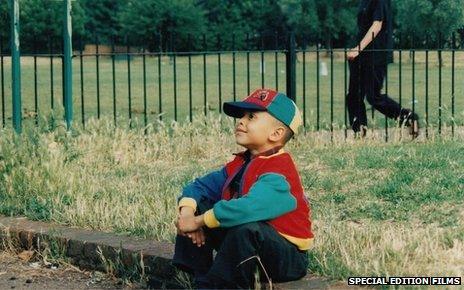

Ashley had four different homes, three different foster families and spent time in a children's home

But once again I can't help feeling that all the emphasis from government and media is, as always, on adoption, to the detriment of the children in care who will never be adopted. We always seem to be overlooked.

While we were making the film, I met a family that gave me hope.

Vicky had been fostered with her family for a couple of years. She wanted to stay with them and they wanted to keep her.

They are not able to legally adopt her but during filming her local authority made her foster placement permanent, meaning she doesn't have to worry about ever being moved.

"You feel really lucky after a while and now there's nothing that I worry about," Vicky confides in me.

"I'm the same as every other child, I'm just obviously not with my real mum and dad, and that's fine with me," she says.

The truth is many of the 80,000 kids in care today will never be adopted - they're either too old when they enter care, or social services feel that there's a chance that their birth parents could one day sort out their issues and come back for them, regardless of how likely that really is.

It's time we put some emphasis and resources on them to make sure they're not left permanently scarred by never having a home or family they can rely on.