What happened to the Methodist central halls?

- Published

Methodist central halls were grand buildings that used to attract thousands of people when the temperance movement was at its strongest. But over the years many have been sold off, with some now used as bars and nightclubs.

The electricity in Manchester's Albert Hall is switched off, and the floor is strewn with broken wood and empty beer bottles.

The pictures of scantily clad women hanging from the walls are a leftover from when the building used to be a bar and nightclub called Brannigans.

But walk up the stairs a little and the huge stained glass windows and beautiful century-old organ give clues about the building's original purpose.

It was a Methodist central hall and, in stark contrast to its recent use as a nightclub, was designed largely to try to keep the urban working classes away from alcohol.

Around 100 were built in major towns and cities across Britain between 1886 and 1945.

At the peak of the central halls' popularity, thousands of people would pack in on Saturday nights for cheap concerts, comedy shows and films, interspersed with hymns and prayers.

In the late 19th Century, at the end of the evening, attendees were often encouraged to sign a vow not to drink alcohol, says Dr Angela Connelly of Manchester University, who has investigated the fate of the distinctive buildings.

Liverpool's Grand Central Hall hosts performances and other events

Nowadays, the X-Factor and Strictly Come Dancing, karaoke and nightclubs are the focus of Saturday night entertainment for many British people.

Only 16 of the halls are still being used by the Methodist Church in their original form, says Connelly.

Many were bombed during World War II. Some were sold off and became theatres. Others have been turned into bars and nightclubs. The Albert Hall in Manchester is now being refurbished to become a live music venue with a restaurant which serves alcohol.

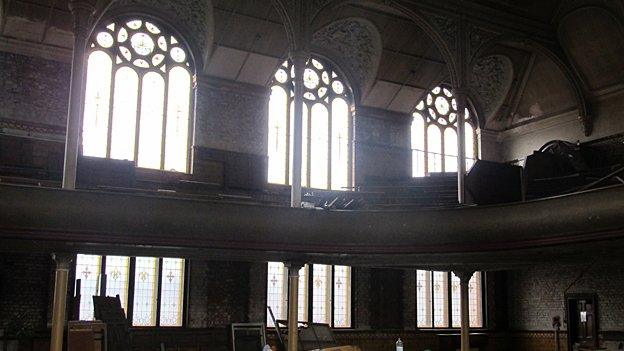

Methodist central halls were often built in a renaissance or baroque style. Despite being in a state of disrepair, Manchester's Albert Hall still has stained glass which hints at a more glorious past...

... including these arched windows...

... and these decorative glass panels set in an ornate ceiling.

And, as in many halls of this type, there is also a century-old organ.

Until recently, the hall was a nightclub, despite its original function being to keep the urban working classes away from alcohol.

At the peak of the central halls' popularity, thousands of people would enjoy cheap concerts, comedy shows and films, interspersed with hymns and prayers on Saturday nights.

Only 16 of the halls are still being used by the Methodist Church in their original form, and Manchester's Albert Hall is now being refurbished...

... and will become a live music venue with a restaurant - which will serve alcohol.

Originally they were intended to be multi-purpose buildings. Shop space was rented out at the front to bring in funds for the church and small rooms were built to host community activities and support groups.

Religious services were held on Sundays, but the Saturday night entertainment was a huge attraction.

"In the late 19th Century, as wealthier people moved to the suburbs, a number of town and city centre churches found themselves with fewer members able to contribute to the upkeep of the premises," says Dr Christopher Wakeling, of Keele University.

"Methodists saw an opportunity to meet the needs of the relatively poor people living in the town and city centres and to do something like what we would call urban regeneration today, so they developed the idea to use town centre street level frontages for shops which they could get an income from and control the moral character of that part of the city centre."

Wesleyan Methodists saw the central halls as being in competition with pubs, music halls and the theatre for the attention of the working class population in cities.

As such, they were built deliberately to not look like churches, but often in a renaissance or baroque style, Wakeling says.

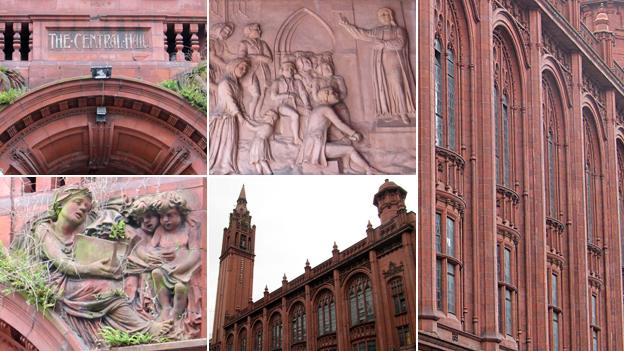

Birmingham's central hall became a nightclub venue and may be converted into flats

The central hall in Birmingham is opposite the magistrates' court. Built in 1903, it has huge, intricately designed windows and its spire towers above many of the other buildings in the area. It's a Grade II-listed building.

But it stands completely empty.

There's a sign for the Q-Club nightclub still on the front, but that was closed in December last year. There's a palpable whiff of urine in the doorway and faded graffiti underneath a sculpture of John Wesley preaching to his followers.

It is reportedly going to be converted into flats.

Stepney Central Hall went through the same process. The Stepney site still has its original front, with a row of shops - including a tattoo parlour, hairdressers and newsagent - but the main hall was knocked down to build the flats.

Shops line the front of Stepney's Central Hall

The football commentator John Motson lived with his family at the hall from 1957 until 1964, while his father was a Methodist minister.

"It was a tough area. My dad had a battle with the prostitutes who lived nearby," Motson remembers. "He worked outside with the community to try to improve things in the area, particularly with the police.

"His main mission was to spread the word about the mission and raise money for the mission."

Liverpool's Grand Central Hall had a bar on the ground floor for several years and is now home to a number of alternative stalls thronged by teenagers and selling everything from T-shirts to incense. The main hall itself is a performance and function venue, with the capacity to serve alcohol.

Connelly says the central halls started to be sold off in the early 1950s. A lot of homes in the major towns and cities had been destroyed during the war, leading many people to leave for new estates and churches in the suburbs.

Further flight from city centres, along with a decline in religious observance, meant that maintaining such impressive buildings wasn't financially sustainable.

One of the central halls still controlled by the Methodist Church is at Westminster. It's an impressive building that doesn't look out of place alongside grand structures like Westminster Abbey, and was the site of the first meeting of the general assembly of the United Nations in 1946.

Now also used as a conference centre, there was reported to be some dissent among Methodists when, in 2005, the church applied for a licence to sell alcohol on the premises.

The impressive central hall at Westminster is still controlled by the Methodist Church

Reverend Stephen Hatcher says that decision is recognition that the Methodist Church has had to adapt to the modern world.

"We have to recognise the kind of world we live in, lots of people drink responsibly," he says. "We have to look at it in a balanced way."

And the same applies to the central halls that are now bars and nightclubs.

"I'm clearly not very happy about it at all," Hatcher says. "But the building is just a shell.

"They are big buildings - you can't carry them if congregations that were 2,000 have gone down to 20."

The Methodist Church needs to find new ways to connect with inner city and secular populations again, he says.

But the days when the church entertained thousands on a Saturday night are long gone.