Paralympics: 10 things you need to know

- Published

After the success of the London Olympics there's unprecedented excitement about the Paralympics. But what are the differences between the two sets of Games?

No Olympic rings

Goodbye Olympic rings, hello Agitos

It may sound similar, and end in "lympic", but the Paralympics are not the Olympics. The iconic interlocking rings have no place here.

Instead there is the Agitos, the three swoops in red, green and blue that represent the Paralympic motto "spirit in motion".

The IOC and the IPC are different

The British team at the 1964 Tokyo Paralympic Games

The two Games - and the International Olympic Committee and International Paralympics Committee - are separate entities. The first international Paralympic Games took place in Rome, external, a week after the 1960 Summer Olympic Games were held there. In 1964, they were held in Tokyo, again just after the Olympics.

But in 1968, Mexico City, the host city of that year's Olympics, refused to host the Paralympics. They were instead held in Tel Aviv and from then until 1988, the Paralympics continued to be held in locations completely separate to the Olympics.

Then in 1988, Olympics hosts Seoul took on the Paralympics, and they have been held together ever since. In 2001, it became official, and now host cities have to bid for both.

There are rumours that one day the two might merge, but opinions are split on the merits of such a move.

Classifications

Sport is only fun or competitive if you pit like against like.

At the Paralympics, you don't have a blind runner competing against one with cerebral palsy - but you may have a person with cerebral palsy competing against someone with restricted growth, which is perhaps a less obvious match.

In order to stream the athletes, they have to go through vigorous testing of function and movement from a sporting medical professional who then gives them a classification.

Swimming has 14 classes. S1-S10 are variations on physical impairments with 10 being least disabled - it covers everything from amputees and spinal cord injuries to someone with dwarfism. S11-S13 are allocated to visual impairments and S14 for those with an intellectual disability.

The S-class refers only to freestyle, backstroke and butterfly whereas SB is breast stroke and SM is individual medley.

An athlete classified as a 9 in freestyle could be a 10 in butterfly - you are classified according to the stroke you're using as swimming on your back could prove more challenging for you depending on your impairment mix. Classifications are also affected depending on whether you have the ability to dive in or start a race from within the pool.

The knock-on effect of having more classifications is that this year's Paralympic swimming as a whole has 148 gold medals up for grabs compared with 34 at the Olympics.

Classifications can be controversial. "There are some who try to cheat their class," says former Paralympian Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson. "When they deliberately cheat it's the same as taking drugs. But some do just fall one side or other of a line and can move up and down between classes."

Sports that are the same but different

Although there are sports that only disabled people play, you'll recognise most of the events at the Paralympics.

Swimming, cycling and athletics will happen in a similar way to their Olympic equivalents, albeit split into many different classifications, and with added prosthetics, wheelchairs and human guides.

Spectators at sports like wheelchair rugby, sitting volleyball and blind football, who are familiar with their able-bodied equivalents, will quickly realise that the Paralympic versions bear little resemblance to the sports they know and love.

The ball used in blind football is less bouncy than a regular one and contains ball bearings to make it audible.

It is played on a hard surface by two teams of five players. The area of play is smaller than in regular football and is surrounded by boards. The boards not only stop the ball from going out, but also reflect sounds from the ball and from footsteps, which helps players to orientate themselves on the pitch.

Outfield players, blind or partially sighted, wear eye covers to level the playing field. The goalkeeper is fully sighted but is not allowed to leave his area. A "guide", also sighted, directs players from behind the goal.

In the absence of visual communication between players, they use specific terms. Shouts of "voy" - the Spanish word literally meaning "I go" but idiomatically "I'm here" - act as a warning that one player is about to tackle another. Teams rely heavily on numerous audible clues, so spectators must stay silent during play.

Sports unique to the Paralympics

There are two sports which are exclusive to the Paralympics - goalball and boccia.

Goalball is played by two teams of three blind and visually impaired athletes, on an indoor rectangular court with tactile markings.

The object is to throw a heavy ball filled with bells into the opposing team's net, while defenders try to block its progress with their bodies.

Boccia features some of the most disabled athletes at the Games. Although it is played competitively in more than 50 countries, it is one of the least well-known Paralympic sports.

A bit like bowls, boccia takes place on an indoor court. Playing individually, in pairs or in teams, athletes roll, throw or kick the balls, aiming to land them close to a target.

It was originally introduced as a game for people with cerebral palsy, but over the years, boccia has been extended to include players with a variety of disabilities affecting motor skills.

Boccia has four disability classifications, BC1 to BC4.

The BC3 class players are unable to propel the ball themselves, so a lightweight ramp is put in place to aid its movement towards the target.

"[BC3 players] are allowed to have an assistant on court with them," says ParalympicsGB boccia team captain Nigel Murray.

"The person who is their assistant has their back to the court so they are unable to see any of the play and they're totally directed in the movement of the ramp by the athlete".

Some players communicate with their assistant through blinking or head movements.

Accessibility

It took five days to turn the Olympic Village into the Paralympic Village.

The venues have increased their wheelchair capacity by removing and rearranging the existing seating - the stadium will have 568 spaces compared with 394 during the Olympics. Blind spectators will be supplied with audio guides, while those with hearing impairments will be seated with a direct view of large screens so they can follow the action.

"The village did have to be Paralympified," says director of Paralympic integration Chris Holmes.

"It was planned from the start. The bathrooms, the signage, the pavement have been fully accessible from the beginning."

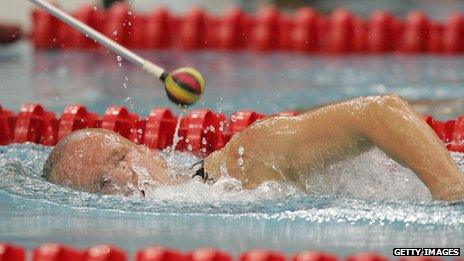

Tappers

Tappers stand at each end of the pool

One of the most important aids to the blind swimmer is the tapper. Standing at each end of the pool is a person holding a long pole with a soft circular ball on the end. As the swimmer approaches they are tapped on the head.

It is a sign to the swimmer that the end of the pool is approaching, and the confidence gained by the tapper's presence means the swimmer can move at full pelt without fearing a painful crash at the end.

"The pole looks a bit like a fishing rod," says Marcelo Sugimori, one of two tappers in the Brazilian Paralympic team. Sugimori used to tap for his sister Fabiana, who won gold in the 50m freestyle in Athens 2004. He now works with the team's two other blind and partially sighted swimmers.

"We tap the swimmer when they are between two and four metres from the end of the pool," he adds.

"It takes a lot of training together, and a lot of trust."

He says that he aims for a single tap, ideally on the head or upper back.

Guide runners for blind athletes

Clegg uses physiotherapy tubing and electrical tape to link her to her guide

Blind and partially sighted runners can compete with a guide. Usually tethered to the athlete by a rope, a guide runs with them, acting as their eyes.

Sprinters Tracy Hinton and Libby Clegg will represent ParalympicsGB in this way.

Clegg, who runs the 200m and 100m, maintains contact with her guide Mikail Huggins, using a loop of physiotherapy tubing, bound in the middle with electrical tape.

She described the process of running with a guide as, "a bit like doing the three-legged race but attached by your hands rather than your feet".

"To execute the run properly you need to be smooth and in time, with both the pace and the stride length correct."

Clegg can run 100m in 12.41 seconds.

The guide talks throughout the race, explaining to the athlete where they are on the track, flagging up bends and making a call on whether or not the athlete should accelerate, hold the pace or relax. They are allocated a lane each.

The totally blind runners, T11 class, will always have a guide, but those categorised as T12 - who have some sight - can choose.

Most blind or visually impaired female runners partner with male guides, as the guide must have the ability to go faster than the athlete.

The golden rule of guide running is not to cross the line before the athlete, a crime punishable by disqualification. Both Clegg and Hinton have lost out on past medals when their guide unintentionally pipped them to the post.

But it is not just runners who use a guide.

Blind athletes competing in the long jump and triple jump also use guides, though here they stay stationary, shouting commands, clapping and directing athletes through the jump.

Age

Viewers new to the Paralympics may notice there are a number of athletes who excel in their field despite being a little older than you might expect sportsmen and women to be.

At Wimbledon this year, commentators were questioning how long Roger Federer could continue at champion level being as he was then the ripe old age of 30. At the Paralympics, however, we find that GB's wheelchair tennis champ Peter Norfolk is 51. Norfolk won gold in Athens and Beijing, is presently ranked third in the world and will be the flag bearer for ParalympicsGB at the opening ceremony.

Much was made of older Olympians as well this year. Hiroshi Hoketsu competed in the dressage at 71. Gymnast Yordan Yovchev, 39, finished seventh in the final of the men's rings. Yamile Aldama, 40, competed for Team GB in the triple jump. In sports like equestrianism and shooting there are plenty of competitors over the age of 40.

But the effect is more pronounced in the Paralympics. GB blind football captain David Clarke is 41, boccia's Nigel Murray is 48, archer Kate Murray 63, discus thrower Derek Derenalagi is in his first Paralympics at 38 and the athletics captain and runner Tracey Hinton is 42.

Athletes may have excelled later than their non-disabled counterparts as a result of choosing to use sport as part of their rehabilitation after acquiring a disability, like Afghanistan veteran Derenalagi.

Other reasons are a little more complicated. The pool of disabled athletes is smaller than that of the Olympics due to lack of opportunity - be that about physical access to sporting facilities or lack of imagination from PE teachers or those supporting disabled people in their development. Self-esteem or simple lack of hands-on experience might mean it never really enters the minds of many who could be extremely capable if supported.

Head of the British Paralympic Association Tim Hollingsworth acknowledges the age differences and says: "The routes into the sport for new athletes are more varied and less predictable than those who've been doing nothing but their sport until this age."

Hollingsworth hopes that the Games will inspire disabled people, non-disabled PE teachers and those in charge to appreciate the possibilities out there.

Hollingsworth is keen to point to a general diversity of age in the GB squad. At the other end of the scale we have wheelchair fencer Gabi Down at 14, sitting volleyball's Julie Rogers at 13 and swimmers Chloe Davies, 13, and Amy Marren, 14.

Drug testing

Paralympic athletes are subject to the same list of banned substances as Olympic athletes. Anyone who requires additional medication for pain or treatment must apply for an exemption.

Each application will be considered on an individual basis by a medical committee. The same goes for Olympic athletes.

"It's a common misconception that a lot of Paralympians will be on prescription drugs. That's not the case at all," says Nicole Sapstead, director of operations at UK Anti-Doping.

"Obviously there are athletes with spinal injuries and they need pain relief. But mostly it is the same as the Olympics - things like asthma and diabetes."

Therapeutic Use Exemptions are granted with a defined dosage for a specific period of time.

The banned substances are the same in both the Paralympics and the Olympics, and athletes on prescription medication must prove that there is no suitable alternative that they could take instead.

Reporting by Damon Rose, Emma Tracey and Lucy Townsend