The time when football fans were hated

- Published

This week's revelations about the cover-up over Hillsborough conjured up memories of an era when the ordinary football fan was often seen as little more than a hooligan.

Hillsborough happened at the end of the 1980s, a decade that had seen the reputation of football fans sink into the mire.

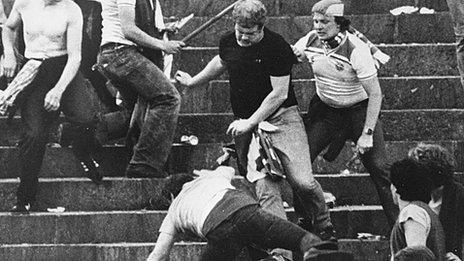

A wave of hooliganism, with the Heysel incident of 1985, external perhaps the most sickening episode, was justification enough for many who wanted to see football fans closely controlled.

Earlier that year, the Kenilworth Road riot saw Millwall fans climb out of the away terrace and storm areas of Luton fans, ripping up seats and hurling them at the home supporters. Luton banned away fans for the next four seasons.

These incidents, involving a minority, had the effect of tarnishing all fans and often led to them being treated like a cross between thugs and cattle.

The fanzine When Saturday Comes (WSC) this week republished the editorial it ran immediately after Hillsborough. , external

"The police see us as a mass entity, fuelled by drink and a single-minded resolve to wreak havoc by destroying property and attacking one another with murderous intent."

It went on: "The implication is that 'normal' people need to be protected from the football fan. But we are normal people."

The 1989 image of football fans as scum - anti-social, violent young men who'd drunk too much - perhaps goes some way to explain the egregious behaviour of some of the emergency services and others after Hillsborough.

The police, a Sheffield Conservative MP and the Sun newspaper among others, shifted the blame for what happened to the fans.

To see fans as part of a mindless mob today seems grossly unfair.

And things have changed dramatically. Anyone attending this week's England game at Wembley would have met courteous police officers and stewards, treating the thousands of fans as they would any other large crowd.

Looking back today, WSC editor Andy Lyons says football was in a completely different place in 1989. The early 80s saw attendances falling. Football was rarely on television - there was a time when ITN stopped giving the football results. The Thatcher government after Hillsborough wanted to bring in a membership card scheme for all fans. "They wanted to treat them in an almost militaristic way," Lyons says.

Fences were seen as a good thing. It was a law and order issue. But football violence was highlighted more than any other violence.

"If there was ever violence at rock concerts or by holidaymakers, it didn't get anything like the coverage that violence at football matches got," Lyons argues.

Hooliganism blighted perceptions of football supporters

Anyone who watched football at that time will have their own stark memories. The stadiums were primitive. Men urinated against walls or into sinks at half-time due to the lack of toilets. What few women fans there were would have struggled to find a ladies toilet.

Fans stood packed together like sardines on the terraces, behind and sometimes under fences.

The policing left no room for the individual. Liverpool fan Tony Evans, now the Times' football editor, remembers an away game at Nottingham Forest where he was kicked by a policeman for trying to go a different route to the police escort. He was heading back to Luton but the police wanted him to travel en masse with those going back to Liverpool.

"When you went to a football match you checked your civil liberties in at the door. The police treated you however they wished."

Class was a crucial part of fan identity. Put a lot of young working class men into cramped surroundings, add tribalism, and you will get problems, Evans says. But usually it was spontaneous flashpoints rather than the "mythologised" organised hooliganism.

The stadiums were ramshackle and noisy. Danger hung in the air along with the cigarette smoke. That was part of the thrill for many young men, Evans says. And it bred a camaraderie that is missing today.

Standing on Liverpool's main terrace - the Kop - there would always be the same few dozen people in a certain spot.

After Hillsborough, Lord Justice Taylor's report into the disaster recommended all-seater stadiums.

"Between 1990 and 1994 football went through a social revolution," says sociologist Anthony King, author of The End of the Terraces.

"How do you break the cycle? You fundamentally change the geography of stadiums. Squalid facilities encouraging and sometimes demanding poor public behaviour have gone."

The 1980s were not a welcoming time for most women on the terraces

The rawness of terrace culture was part of the problem.

"The crowd generates an intoxicating collective effervescence," he argues. "This is where the point about everyone getting treated like scum comes in. Sociological research has shown that even people with no intention of engaging in violence or disorder change in that environment."

Culturally football has moved to the mainstream. Lyons says fans have gone from being participants to consumers. Stadiums are modern and well run, with numerous catering concessions and sensitive policing. It is the post-Nick Hornby era of the middle class football fan. Live games are on TV almost every night of the week. Everywhere one looks, football fans lurk, from political high office to the Royal family, the arts and business.

Money has poured in as the game has globalised. The police, authorities and media could no longer get away with the kind of attitude that fans were treated to in the 1980s.

Evans bemoans the fact that a child growing up in East Anglia is today as likely to support Barcelona as Norwich City.

The 1980s football culture had to change. "So much of that was bad and needed to be got rid of," he says. "But with it has gone so much good that made the game grow. Part of me misses that rawness, the primitive conditions and the ability to turn up and watch football wherever and whenever I want without a season ticket."