The shared language of sport and politics

- Published

Sporting metaphors always overrun the language of politics in the English-speaking world at election time - and perhaps most of all in the US.

We have now reached the point in the race for the White House when it helps to keep a glossary of American sporting terms ever close at hand.

True, we have not quite reached the bottom of the ninth (the final, often dramatic, inning of a baseball game).

It is probably too early for the front-runner Barack Obama to start running down the clock (cautious tactics used by the team ahead in the final minutes of a basketball match designed to protect its lead).

Three presidential debates still lie ahead, where Mitt Romney will doubtless be looking for a knock-out punch (one of the few analogies that requires no translation outside the US).

Even after the debates, there may still be time to hurl a Hail Mary pass (a desperate long pass thrown by the quarterback in the dying minutes of an American football game in the hope of getting a touchdown).

Certainly, he needs a game-changer (some dramatic "play" that will upend the contest). In the all-important battleground state of Ohio, the Romney camp has accused the Obama campaign of already spiking the football (a touchdown celebration when the player spears the ball into the ground).

Across the political Anglo-sphere, the language of sport often doubles as the language of politics.

At Westminster, cricketing metaphors are not uncommon. The sticky wicket, the straight bat, the hit-for-six.

When the former Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe delivered his dramatic resignation speech attacking Margaret Thatcher, he likened her handling of negotiations with Europe to "sending your opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find the moment the first balls are bowled, their bats have been broken before the game by the team captain."

In Australia, the preferred national metaphor is a sporting one: the country punches above it weight. In the daily rough and tumble of Canberra life, politicians also often accuse each other of playing the man not the ball.

In Canada, ice hockey naturally provides the analogies. Politicians are sometimes described as pylons (hopeless defenders that attackers can skate round at will). Occasionally they have to stickhandle an issue (which means to retain possession of the puck with some artful individual stick play).

Still, it is in US presidential politics that sports-speak is most prevalent. During the convention season, the test of a speech is whether it is hit out of the park or remains within the confines of the auditorium - which, fittingly, now tends to be a sports arena.

At the Democratic convention in Charlotte, for instance, Bill Clinton was deemed to have hit a home run for Obama. The previous night, the First Lady Michelle Obama had also swung for the fences and connected.

So when it came for the President to step up to the plate, this was how the veteran commentator Mark Shields framed Barack Obama's address (or, as he described the speech in a panel discussion on the American television network PBS, his at bat). "He can't get by with a ground rule double tonight (when a batter is allowed to advance to second base when the ball has bounced out of the playing area). He has got to hit a home run." Then, switching sports and metaphors, he added: "I mean, they [Clinton and Michelle Obama] have set a bar that is that high."

Convention coverage is modelled on half- and full-time sports shows, with pundits perched in glass-fronted Sky boxes providing a running commentary on the action down below. "Did she move the ball?" asked a US cable anchor at the Republican convention in Tampa, lapsing into gridiron-speak, after Ann Romney had just wrapped up her speech.

Then he threw to a correspondent on the convention floor, mopping up reaction much like a touch-line reporter at the end of a football game. Even the favoured bellow of convention delegates started out as a sports chant: "U-S-A, U-S-A."

In print as well, front-page campaign news is delivered often in back page prose. In a classic of the genre, this was how the New Yorker described Mitt Romney's decision to pick the Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan as his vice-presidential running mate.

"Such an abrupt reversal smacks of desperation," wrote political reporter John Cassidy. "Not a Hail Mary pass, exactly, but akin to a struggling NFL team that suddenly decides to adopt the wildcat formation and rely on fakery" (an attacking move where the ball is "snapped" directly to the running back rather than the quarterback).

In the coming days, as we approach the televised debates, boxing will supply the metaphors. The talk will be of knock-out punches, even though relatively few debates have finished with much blood on the canvas. In the classic Kennedy-Nixon debates in 1960, the first in US political history, it was not the then Vice-president's glass jaw that was the problem but rather his sweaty upper lip. Go back and study the tapes: from Kennedy, you will not find a smack-down blow.

Success in the debates often bestows upon the winning candidate the Big Mo (unstoppable momentum), a phrase that has become such an integral part of the political vocabulary that it is easy to forget that it comes from 1960s gridiron football.

Politicians speak this sporting patois just as fluently as journalists and pundits. Earlier this month, as the college football season got under way, Mitt Romney urged voters to hire a new coach because "it's time for America to see a winning season again." Obama responded in kind with a string of sporting analogies: with an economic play-book so badly flawed, he said, Romney would produce a losing season.

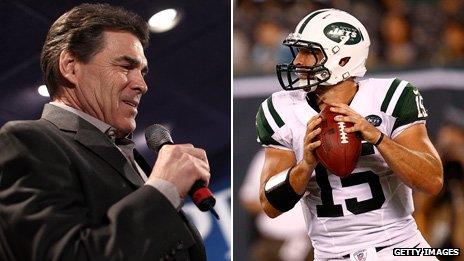

Rick Perry optimistically compared himself to quarterback Tim Tebow

During the primary season, one of the more memorable moments came when the Texan governor Rick Perry tried to revive his hapless campaign ahead of the Iowa caucus by likening himself to Tim Tebow, a quarterback with the New York Jets famed for producing miraculous come-from-behind victories.

Linguistically speaking, should sport and politics mix? Media commentators have long bemoaned a style of campaign coverage known as "horse-race journalism," in which the contest becomes everything - although a better description might be "play-by-play journalism."

Strategies and tactics subsume policies and ideas. Politicians tend to be judged as players in the political game, rather than as potential leaders. I know this to be true, because, as a one-time Washington correspondent, I fell back on these analogies myself.

Each electoral cycle, news organisations vow to cover the issues in depth and not be consumed by gaffes and trivialities that habitually dominate coverage. But while there is no shortage of serious-minded policy analysis, reporters generally end up commentating on the game, with a scoreboard constantly updated with the latest polls.

Given the hurtling pace of modern-day news, and the demands for rapid response online analysis, horse-race journalism has, if anything, got worse. Who is up or down is now a matter of instant judgment and, in the main, pinched thinking. As a Tweeter myself, external, again I plead guilty.

Soon this interminably long race will be over - it is a marathon, remember, not a sprint - and there will follow another of the great rituals of campaign coverage. Correspondents will identify the single moment the election was won or lost, or the strategy or move that led to defeat - which will seem obvious now, even if it wasn't at the time. Needless to say, the Americans have a name for this kind of post-match analysis: Monday morning quarterbacking.

Tweet @BBC_Magazine using the hashtag #slamdunkpolitics when you hear sporting metaphors used in politics.