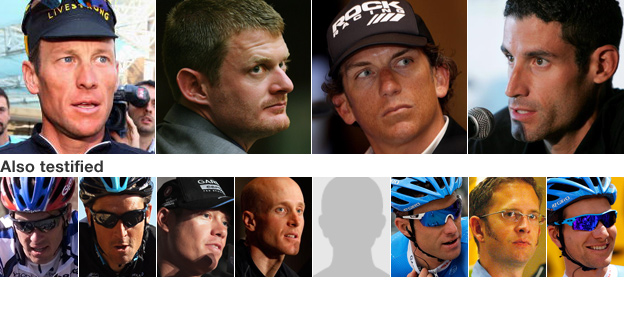

Lance Armstrong: Tyler Hamilton on 'how US Postal cheated'

- Published

Lance Armstrong

The seven-time winner of the Tour De France ran 'the most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping programme the sport has ever seen', according to the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA).

Floyd Landis

Stripped of his 2006 Tour De France title in 2010. After admitting doping, Landis made allegations against Armstrong and later testified to USADA against him.

Tyler Hamilton

Hamilton failed a number of doping tests in 2004 and 2009 and was forced to retire. In 2011, he claimed that he and teammate Armstrong had taken performance-enhancing drugs together.

George Hincapie

The captain of Armstrong's team from 1999-2005 and described as his best friend. His doping admission leaves Armstrong as the only member of the team not to admit to using drugs.

Frankie Andreu

Team captain of the USPS team in 1998, 99 and 2000. Admitted doping in 2006.

Michael Barry

Rode with the USPS team from 2002-06. Admitted doping in October 2012, banned for six months and stripped of race results from May 2003 to July 2006.

Tom Danielson

Suspended for six months after admissions of using performance-enhancing drugs. Race titles from March 2005-2006 cancelled.

Levi Leipheimer

Rode with the USPS team from 2001-01. Received a six month ban and stripped of race results from June 1999 to July 2006, and during July 2007.

Stephen Swart

New Zealand cyclist who rode with Armstrong in the Motorola team in 1995. Has accused Armstrong of pressing for team to use doping.

Christian Vande Velde

Postal team rider from 1998-2003. Says Armstrong was the 'enforcer' of the doping programme

Jonathan Vaughters

Rode with Armstrong from 1998-1999. Gave testimony about USPS' system to avoid drug testing.

David Zabriskie

Postal team member from 2001-2004. Gave evidence about the doping culture within the team.

Eleven of Lance Armstrong's former team-mates have told their stories of doping with the US Postal Service cycling team, but none in such detail as Tyler Hamilton.

His book, The Secret Race, published in September, provides minute detail on how the drugs were obtained, how they were stored, delivered to the riders and injected, and how the syringes were carried away in a Coke can.

Most astonishingly, he explains how easy it was to beat the testers.

Lance Armstrong has rejected Hamilton's allegations, while his lawyer described the latest condemnation from the US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) as a "one-sided hatchet job".

Hamilton started off on testosterone, a "red egg" as the cyclists referred to the pill, but soon graduated on to the more powerful EPO - erythropoietin - which he and his US Postal Service team-mates dubbed Edgar, after Edgar Allen Poe.

This stimulates the creation of red blood cells, boosting performance by about 5%, or, as Hamilton puts it "roughly the difference between first place in the Tour de France and the middle of the pack".

EPO can be detected in the body for a number of hours after it has been taken - the "glowtime". During this time, the cyclist needs to avoid a meeting with the dope tester.

So, during the months of training, they kept track of when they had taken the drug, and tipped each other off by phone whenever a tester appeared in Girona, the town in northern Spain where the cyclists were based. In The Secret Race, co-authored by journalist Daniel Coyle, Hamilton lists three tips:

"Tip one: Wear a watch. Tip Two: Keep your cellphone handy. Tip three: Know your glowtime, how long you'll test positive after you take the substance. What you'll notice is that none of these things is particularly difficult to do."

They were more like "discipline tests, IQ tests" than drug tests, he says.

"If you were careful and paid attention, you could dope and be 99% certain that you would not get caught."

On one occasion Hamilton heard a knock on the door when he was glowing, and simply hid inside the house in silence until the tester gave up and went away.

They never came during the night, making late evening the best time for doping. One elderly tester even called in advance to let the cyclists know when he was coming.

"The most conventional way that the US Postal riders beat what little out-of-competition testing there was, was simply to use their wits to avoid the testers," says the Usada report published on Wednesday.

It adds that Armstrong sometimes stayed at an out-of-the-way hotel where he was "virtually certain not to be tested".

Armstrong is described in the report as the enforcer of US Postal's "massive and pervasive" doping programme.

"It was not enough that his team-mates give maximum effort on the bike," Usada says. "He also required that they adhere to the doping programme outlined for them or be replaced."

But it wasn't only US Postal that was doping, of course. More than half the Tour de France winners since 1980 have either tested positive, been sanctioned for doping, or admitted it.

Talking to BBC Radio 5 Live, Hamilton said this week that it was "a dark period of cycling that we all went through".

"None of us when we were 15 or 16 years old were planning on doing that, but we all kind of rode our way up the ranks and came into this world. It was a world that already existed, when we got there. The doctors, the riders had been doing these things for years."

George Hincapie, US Postal team captain from 1999-2005, admitted doping for the first time on Wednesday, saying that early in his professional career it became clear to him "that given the widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs by cyclists at the top of the profession, it was not possible to compete at the highest level without them".

Hamilton writes in The Secret Race that he visited Armstrong at his home in Nice some time before the 1999 Tour de France, and finding himself without EPO, asked if he could use some of Armstrong's.

"Lance pointed casually to the fridge. I opened it and there, on the door, next to a carton of milk, was a carton of EPO, each stoppered vial standing upright, little soldiers in their cardboard cells."

In 1998, the team had distributed the EPO in white lunch bags. But this was the year the Festina and TVM teams were caught with large quantities of steroids, EPO and syringes. So in 1999 greater care was needed. According to Hamilton, Armstrong arranged for his gardener to follow the Tour on a motorbike, carrying a thermos flask full of EPO tubes.

"When we needed 'Edgar', Philippe would zip through the Tour's traffic and make a drop-off," he writes in The Secret Race.

By the following year, they had begun blood doping, flying to Spain to have their blood drawn by the team doctor, Hamilton says.

This blood, rich in red blood cells, was then delivered back to the tired riders, to help boost their red blood cell count during the race.

Riders found blood bags, still cold from the refrigerator, taped to the wall next to their beds in their hotel rooms. Hamilton describes the sensation of goosebumps as the chilled blood circulated around his body.

One of the doctors used by US Postal, Michele Ferrari - nicknamed Doctor Death by reporters - found ways of helping to reduce the EPO glowtime by using small "microdoses" injected directly into the vein, Hamilton says.

The cyclists could also drink large amounts of water, or inject themselves with saline solution, in order to accelerate the fading of the glow.

"They've got their doctors, and we've got ours, and ours are better," writes Hamilton.

After Ferrari was convicted of sporting fraud by an Italian court in 2004, Armstrong issued a statement, in which he said: "I have always said that I have zero tolerance for anyone convicted of using or facilitating the use of performance-enhancing drugs. As a result of today's developments, the USPS team and I have suspended our professional affiliation with Dr Ferrari." Ferrari's conviction was overturned on appeal.

Armstrong contests that he took 500 drug tests worldwide and never failed one. This is disputed. Hamilton says he failed tests, but managed to explain it away, or hush it up.

The Usada report takes the same line. It says Armstrong was subjected to "considerably fewer" tests than he and his lawyers claim, and contends that a medical prescription Armstrong produced to explain a failed blood test in 1999 was bogus.

Hamilton himself kept a clear record for several years. He first tested positive just as he reached the peak of his career - a gold medal at the 2004 Olympics - when by mistake he was given another man's blood.

Blood transfusions are potentially risky. Badly stored blood can poison an athlete when transfused. Hamilton never had this problem, but he did suffer from one botched transfusion, which left him urinating a fluid "dark, dark red, almost black".