Kateri Tekakwitha: First Catholic Native American saint

- Published

The first ever Native American saint has been canonised by the Roman Catholic Church in a ceremony at the Vatican. Kateri Tekakwitha - sometimes known as Lily of the Mohawks - died more than 300 years ago, but is thought by some to have performed a miracle as recently as 2006.

"It's a third-class relic," says gift shop manager Joanne Wiesner, wide-eyed as she holds a small Kateri Tekakwitha prayer card in her hand.

Embedded within the card is a little piece of cloth which has touched a fragment of bone, a first-class relic, from the soon-to-be saint.

"I get goose bumps every time I think about it," says Wiesner.

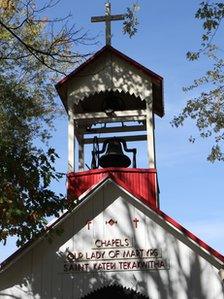

The prayer cards are selling like hot cakes at the Shrine of Our Lady of Martyrs in Auriesville, set amid the beautiful wooded hills of what was once Mohawk land.

It was in a village here, then called Ossernenon, that Kateri Tekakwitha - a Native American Mohawk woman - was born in 1656.

This was a time of huge upheaval, violence and disease, says Allan Greer, a professor at McGill University in Montreal who has written a history of her life, Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits.

There was fierce fighting between rival Native American communities - Kateri's mother was an Algonquin who had been captured in a raid by the Mohawks.

But Dutch, English and French colonialists were also competing for control of the territory, bringing with them both guns and disease. When a smallpox epidemic struck, it killed her parents and younger brother. She survived, but the disease left her face scarred and her sight seriously impaired. The Mohawk word "Tekakwitha" roughly translates as "the one who walks groping her way".

Seeing so much death and disease in their midst, the Mohawks believed French Jesuit missionaries were responsible, and held them accountable.

Just a few years before Kateri was born, three were caught, tortured and then brutally killed in her village (they were themselves later canonised, external).

But when Kateri was young, a peace deal was struck with the French, and part of the deal was that missionaries would be allowed to work within the communities.

By this point, Kateri was living over the river in a small village called Caughnawaga, which is the only Mohawk village anywhere to have been substantially excavated.

Set on a hill for protection, so that the Mohawks could see their enemies coming, coloured poles today mark the plots where they lived in traditional longhouses, with bunks to the side, and fires inside to cook and keep warm in the bitter winters.

"It's a place of peace and healing," says Friar Mark Steed, who is in charge of the site, known as the National Kateri Tekakwitha Shrine, in the village of Fonda.

"This is where she lived. It's the land where the Mohawk people lived. It's a sacred place," he says.

"Being on this land is like being in a church."

It is a short walk through the woods to the echoey well and the water where Kateri Tekakwitha was baptised into the Catholic Church at the age of 20, on Easter Day 1676.

She is sometimes said to have been one of the only members of her community to convert to Catholicism, but up to half of her village may have converted, according to Allan Greer.

For some, it was as much a practical and strategic move, as a religious one, he says.

"The Mohawks were walking a delicate balance trying to align themselves with allies, without becoming dependent.

"It was a kind of diplomatic alliance in many ways."

But Kateri appears to have been penalised for converting. Her uncle, the chief of the village, is said to have been unhappy with her decision, and her refusal to marry a Mohawk man he had selected for her.

Kateri ended up travelling 200 miles (320 km) by foot and canoe to a Jesuit-run Native American missionary village near Montreal, called Kahnawake.

There she proved herself to be pious in the extreme.

She took a lifetime vow of chastity, and subjected herself to a harsh regime of self-punishment, which included walking barefoot in the ice and snow, placing hot coals from the fire between her toes until they cooled, and lying on a bed of thorns.

Jesuit missionary Pierre Cholenec, who lived in the Kahnawake community at the time, wrote: "She tortured her body in every way she could think of: by toil, by sleepless vigils, by fasting, by cold, by fire, by irons, by belts studded with sharp points, and by harsh disciplines with which she tore her shoulders open several times a week."

The Jesuits felt she was going too far, says Orenda Boucher a Mohawk academic and researcher from Kahnawake, which is still a Native American community today.

Mohawk men would conduct all sorts of tests of strength and willpower before going into battle, she says, and Kateri Tekakwitha was probably influenced by this, effectively fusing her native beliefs with her newfound faith - practising what Greer calls a kind of "intense indigenous Catholicism".

Kateri Tekakwitha died when she was just 24 years old - and it was upon her death that reports of miracles began.

Jesuits at the scene said that the scars on her face vanished entirely, and soon after, a number of people reported seeing visions of her.

The Jesuits believed her to be a saint and catalogued all they could of her life, making her the most well-documented indigenous person in the history of the Americas, says Greer.

But some Mohawks in Kahnawake today are ambivalent about their ancestor, says Boucher. Many people don't identify with her story of life as a virgin - it's a culture where motherhood and caring for children is seen as central to a woman's role - and some associate her with the bitterness of colonisation, loss of land, and Mohawk tradition.

Many in the community there are in fact moving back towards their traditional beliefs, and away from the Catholic Church, says Boucher.

But there is a sizeable Native American Catholic contingent in the US - 680,000, external according to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, out of a total population of 2.5 million, and in some areas, the vast majority of Native Americans are Catholic.

And for decades, a dedicated group of Native American Catholics across the US have been praying - first for her beatification, which came in 1980, and since then for her canonisation.

"It meant a lot to learn about this young Mohawk woman. She is one of us," says Sister Kateri Mitchell of the Tekakwitha Conference, a body that represents Native American Catholics in the US.

"People have become very intrigued about her life - how this young woman of the 17th Century has influenced the lives of so many in the 21st."

Sister Kateri visited the shrine many times with her parents as a child, and played a part in the recent reported miracle that secured Kateri Tekakwitha's canonisation.

This was in 2006, when Jake Finkbonner, a five-year-old half native Lummi boy from Washington state fell playing basketball and hit his lip against some metal, contracting a potentially deadly "flesh-eating" bacterial infection, necrotising fasciitis.

Sister Kateri Mitchell put the word out for people to pray to Kateri Tekakwitha for his recovery. She then went to his bedside in the hospital in Seattle with a piece of Kateri's wrist-bone - a first-class relic - which she placed against his body, and together with his parents, prayed.

Jake, now 12, still needs some medical attention, but he made a recovery considered by some, including the Vatican, to be miraculous.

At a retreat at the Auriesville shrine almost everyone has a story of help or healing that they attribute to Kateri Tekakwitha - from helping a small burn to heal, to curing someone's mother's kidney disease, or helping a girl born blind to see.

Even some Catholics are sceptical about miracle stories, but since December when Pope Benedict XVI announced that Kateri Tekakwitha would be canonised, busloads of curious visitors have been arriving at the shrines.

"When I came here, it was a very quiet place. And I like things quiet," laughs Friar Mark Steed at the shrine in Fonda.

"Then all of a sudden they make this announcement that she's going to be a saint, and the world explodes around you."

He says he wants to avoid a "circus" developing around the shrine, and to keep it as a simple place of prayer - one that is also true to the saint's Mohawk roots.

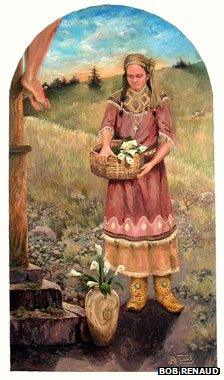

"As a child I remember just being in awe of that place. I've always had a spot in my heart for Native American history," says teacher and artist Bob Renaud, who lives just over 100 miles (160 km) north in Carthage, and who has painted images of Kateri Tekakwitha - one of which looks set to become part of the Vatican collection.

"There's a special feeling you get at that place. You can definitely feel the spirit.

"She stood up for what she believed in, and she stood strong.

"She's local. She's not in France - she is of America. We are pretty honoured to have her so close."