At home with Julian Assange

- Published

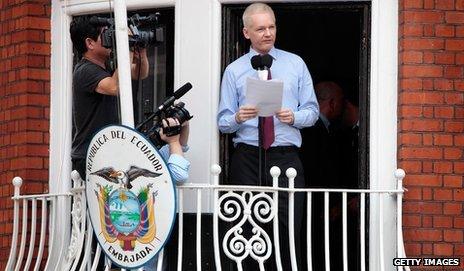

Julian Assange has been living in the Ecuadorean embassy in London for the past four months. What is day-to-day life like for the Wikileaks founder - and for his diplomatic hosts?

There is something wonderfully refreshing about the Ecuadorean ambassador in London. We meet Ana Alban at the embassy, just round the corner from Harrods in Knightsbridge.

"We are almost all women here," she tells me and laughs.

She seems very relaxed about the guest holed up in her embassy, causing diplomatic relations between her country and the UK to take a nosedive.

Last June the embassy had a surprise visitor - Julian Assange, the founder of Wikileaks, who was seeking refuge to avoid extradition to Sweden where he faced questions on sex assault allegations.

It's been four months now and embassy life has changed.

The number of staff has doubled, and visitors, including celebrities such as Lady Gaga, arrive in a constant stream.

Police are stationed outside. It has certainly put this small embassy on the map.

We are here to talk to the people working in the embassy, and possibly to Julian Assange as well, although this is uncertain. He is nowhere to be seen. We meet the consul, Fidel Narveaz and settle down in his office.

"While the decision was being taken [to grant him asylum], a member of the diplomatic staff needed to be here full time and that was me."

Fidel points to the shiny leather sofa where he slept.

I ask him whether he has got to know Mr Assange well.

"Yes, he is a very interesting man to meet."

"Is he the sort of person you love or you hate?"

"Yes."

"Do you admire him?"

"Yes I do, definitely do."

His foot taps the floor when he finishes a sentence and his hand beats the back of the sofa.

I bring up the sexual offence allegations.

"We all think that it is fair for him to face that… Ecuador has never said he shouldn't face any allegations that are taking place in Sweden.

"What we don't want is for him to be extradited to the United States and be submitted to inhuman treatment for political reasons, so Ecuador has made clear from the beginning we would like facilitate investigation in Sweden to go forward.

"The only condition for us is that there should be undertakings for him not to be extradited elsewhere for political reasons."

He takes me on a tour of the flat. It's not huge. I point to a door at the end of the corridor and ask if I can look inside.

"No, that is where he is staying."

"That's where Julian Assange is?"

"Er, yes."

"I can't just knock on the door?"

"Well no, not yet, every visit needs to be announced with anticipation."

Ana Alban - Ecuadorean ambassador, and Julian Assange's host

We wander up the corridor and find the ambassador waiting for us in her office. I ask her to recall when she first heard that Julian Assange had come to the embassy.

She was at a meeting, she says, and raced back so Julian Assange could make his formal request for political asylum.

"Did your heart sink at that moment?" I ask.

"At that moment the only thing I was thinking was how to manage him sleeping here. Maybe because I'm a woman I was thinking of the sheets - we still don't have a washing machine.

"I'm sure that a man would not think of those details at that moment."

She is smiling broadly and then that laugh erupts.

In mid-August, a couple of months after Mr Assange's arrival, the Ecuadorean government received a letter from the UK foreign office. In this letter, she says, the UK government threatened to storm her embassy.

But it wasn't only the letter, she says.

"That letter came with a gift, the gift was numbers and numbers of policemen outside the embassy. It was a crazy night."

She tells me that late that evening the road was closed. More police turned up. They were outside every window, she remembers.

But she says her biggest shock came when she went to the embassy toilet.

"I turned on the light on and was about to go to the loo, see, and out of the window were police officers." She bursts again into laughter.

I ask her what she made of the action.

"It was the biggest mistake that I have seen since I arrived."

"Why?"

"I am not Mr Hague's brain, so you had better ask him. But I think in the beginning they were trying to show this little country that Britain is still an empire and we should learn how to be good boys during our stay here."

I am told that Julian Assange will now allow me to ask three questions. My mind goes blank -I can't think of the three questions I should ask.

I walk to the end of the corridor and knock on the door. Inside I find a very pale man sitting at a round table with three women, all with open laptops.

It's a medium-sized room with a partition, behind which he tells me is his bed.

Post-it notes cover the walls. Books and phones and files are scattered about. It smells a little stale.

Julian Assange speaks in a monotone, and so quietly I can barely hear him.

I ask how he is is coping. Does he get bored?

He answers very slowly.

"It's not particularly different for me, I had 10 days solitary confinement in this country, 18 months under house arrest with a manacle around my ankle. It's normal for me."

What about exercise?

"I have very solid friends here, some from the UK military and they come and train me."

"What - in this room?" I glance around. There's so much stuff that it doesn't seem big enough to do press ups or boxing (I was told earlier he liked to box).

"In the bathroom," he says.

I ask him about Lady Gaga's visit and Twitter. Is there anything in the chain of events leading to this room, that he regrets?

There is a long pause.

"I regret the UK government elected to subvert its own principles absolutely."

One of the women says this is my last question. She says she is sorry, but I did interrupt a meeting.

I apologise and ask Assange directly about the allegations he faces in Sweden. He interrupts me before I have finished my question, in a louder, more animated, voice.

"That doesn't sound like a good start," he laughs.

He and the women list all the things he has been accused of - mass murder, bad diet, poor personal hygiene.

They seem to be saying that any suggestion that Assange raped and sexually assaulted two Swedish Wikileaks supporters is just another step in a campaign to smear him. It's the spin that he minds, he says.

As I leave he warns that there is a lot of sloppy journalism around and I should always go to the original source.

Before we go Ana Alban tells me that Pricilla, the receptionist, is the most important person in the embassy. She meets all the celebrities and also has to cope with the mountain of mail that now arrives for their guest. Each post brings more books and presents and food.

"And teeth," Pricilla adds. I've clearly misheard.

"Tea?"

"No teeth, animal teeth."

The ambassador begins one of her full-throttle laughs. It seems there is no end to the absurdity of her life at present.

But neither is there any end in sight for Julian Assange's life at the Ecuadorean embassy.