Ceefax: The early days

- Published

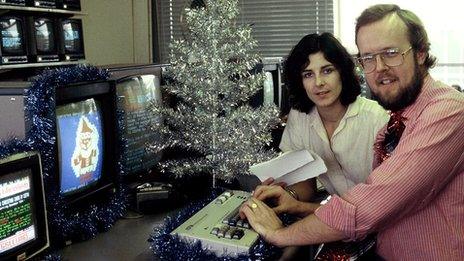

Mort Smith and colleague prepare the Ceefax Christmas special

Ceefax is being laid to rest. Mort Smith, who worked on the service during its early days, remembers the pioneering teletext service.

The invention of teletext back in the early 1970s was something of an accident.

BBC engineers based down at the research department at Kingswood Warren were actually trying to find a way to provide programme subtitles for the hard-of-hearing, using an otherwise unused part of the 625-line television signal - called the field blanking interval.

They succeeded - but in so doing, it quickly became apparent that the same principle could be used to send all kinds of other messages - news, sports results, financial information, weather reports - and Ceefax was born.

In 1974, long-serving BBC journalist Colin McIntyre was given the job of editor, charged with building and launching the UK's first teletext service.

It formally took to the air in the autumn of that year.

McIntyre recruited a team of eight to work on the fledgling service - four sub-editors and four research assistants - who were based at BBC Television Centre in Shepherd's Bush, initially in a small room on the sixth floor of the building.

The early days of the service proved anything but hi-tech.

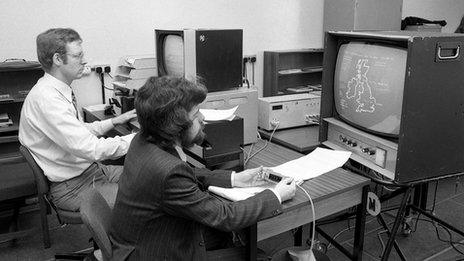

Ceefax journalists would monitor incoming wire copy from Reuters, the Press Association and the BBC's own internal news distribution service, GNS, and when a story was to be updated they would type at one of two production terminals and create a Ceefax page.

Then they had to produce a punched tape - approximately a metre long - and take it down two flights of stairs to the Central Apparatus Room (CAR), load it into a tape reader and watch as it was read into an anonymous metal box called a core store which actually transmitted the pages (It could hold a mere 24 pages at that point).

A walk back up to the sixth floor followed and if, at that point, it was discovered that a spelling mistake had been made, the journalist had to go through the whole process again. It ensured close attention to detail when writing.

When Ceefax launched, it was rumoured that there were only four teletext-capable TV sets in the whole UK - one in the BBC director general's office, one for the director of engineering, one at Kingswood Warren and one in Colin McIntyre's home.

It proved an invaluable service for the editor who used to alert his wife that he was about to leave Television Centre on his way home by using a back page on Ceefax.

The early teletext decoders consisted of large metal boxes - wire-wrapped prototypes.

Although the process was unwieldy, those who worked on Ceefax during the pioneering days were conscious that they were taking part in an information revolution of some magnitude long before the world wide web arrived on the scene.

As the service developed, more unused signal capacity was devoted to it and Ceefax moved into its first permanent home in Room 7059 on the top floor at Television Centre.

It wasn't just breaking news that found its way into the growing portfolio of information carried on Ceefax. Sport, business, travel and weather forecasts were added to the service.

McIntyre also insisted that the service contain a page of quirky stories which he called "Charivari" and which gave the journalists liberty to put in the occasional item that wasn't quite "BBC" in style or content.

There was a lot of experimentation to try to find which colours worked best for conveying information effectively.

McIntyre commissioned a study from the London School of Art and Design into which of the seven teletext colours was the easiest to read.

Some colours worked better than others

Green turned out to be the easiest, followed by cyan (light blue) and yellow, with white also acceptable. Red, dark blue and magenta were no-go areas according to the experts and so Ceefax copy tended to use only the "viewer-friendly" colours.

Some sub-editors developed an uncanny skill for producing recognisable pictures using the chunky Ceefax graphics.

Chief among them was Ian Irving - another of the original team - who revolutionised the look of the service by introducing stylish graphic headings for the various sections, weather maps, cartoons and all kinds of special designs.

He later went on to create a long-running cartoon serial called 4-T about a little dog for the Channel 4 teletext service, 4-Tel.

Ceefax also started to cater for those interested in leisure.

Programme listings for the broadcast channels, film, book and car reviews, recipes, holiday tips, kids quizzes and puzzles all became a regular part of the Ceefax diet.

One one occasion in 1976 the editor asked me and another of the journalists, Georgina Howarth, to put together a Christmas special consisting of quizzes, Christmas facts, an advent calendar with a different festive graphic behind each "door" (shown by pushing the "reveal" button on the keypad) and Christmas TV guides.

We then came up with the ridiculous idea of running a bingo competition.

We concealed hidden numbers on some of the pages and invited people to write into TV Centre for a set of six printed bingo cards - so the whole family could play along.

To find the hidden numbers, punters used to have to look at every teletext page every day for a 10-day period - literally hundreds of pages.

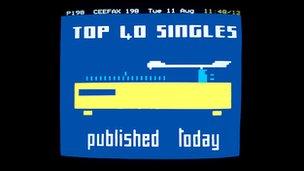

Ceefax bingo competition - now closed

We thought we'd be lucky to get 100 entries - we got 5,000 fully completed cards - and the prize was just a £10 book token.

There was another competitor for Ceefax - ITV also had its own teletext service called Oracle (standing for Optional Reception of Announcements by Coded Line Electronics) and there was always a race between the two services to see who could get something to air first.

A new system was installed to handle the transmission of Ceefax pages with the main computer standing in the corner of the production office.

McIntyre named the machine Esmeralda and she turned out to be a somewhat fickle and contrary soul who had a habit of refusing to work on a regular basis.

This called for someone to push the re-boot button on her control panel which shut the system down and re-started it - a process that could take up to five or six minutes to complete.

The record number of re-boots in a single day stood at just over 240 before the problem was finally solved.

Eventually, in the late 1970s, British computer systems company Logica was given the task of building a whole new production, transmission and management system that proved both successful and durable.

Shortly thereafter, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher attended a special function to announce the production of the millionth teletext-equipped television.

From its small beginnings, British standard teletext eventually percolated out across the whole world with services appearing on the signals of national broadcasters and independent stations as far apart as Malaysia, Germany, Holland, Scandinavia, Hungary, Switzerland, South Africa, Australia and even the Soviet Union.

For those who worked on the service in those pioneering early days, the final switch-off of the last teletext signal in the UK will be greeted with some sadness.