Stories of love and loss in a desert war grave

- Published

Remembrance Day on 11 November is observed in many of the war dead cemeteries run by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission around the world. The BBC's Kevin Connolly visits one in Libya, which brings alive to him World War II's North African campaign and the weight of sadness it left behind.

They came to the shores of the Mediterranean with rifle and pack rather than bucket and spade and now they lie in silent rows, not far from where the turquoise water nudges lazily against the beaches of Tripoli Bay.

This is a time of remembrance but to walk through the headstones of Portland stone in this war cemetery is to remember how much we have forgotten too.

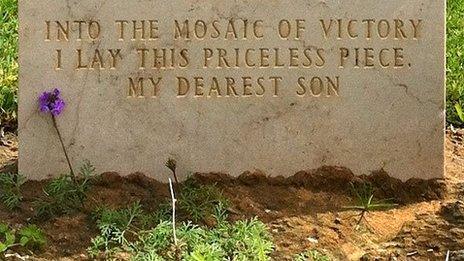

One of the inscriptions says simply: "Into the mosaic of victory I lay this priceless piece."

Some mother or father or wife far from the battlefield where their soldier died, sensed that the loss which filled their thoughts and broke their hearts was an unfathomably small part of the largest of all human dramas.

In Tripoli you are reminded of just how complex that mosaic was - and how the last act of Britain's creaking empire began with this gathering of the pieces from across its far-flung territories.

Commonwealth war graves are designed to evoke the spirit of English gardens - even in places like this, where the burning North African heat means the trees are palms rather than oaks.

So you are somehow not surprised to find Highlanders and Life Guards here and the names of ancient county regiments - Sussex and Cornwall, Dorset and Durham.

But into the fighting in North Africa Britain threw forces from places where the tranquillity and symmetry of a cottage garden would have seemed an impossible luxury.

South Africans who served in the Tripolitania Civil Police Force lie alongside the dead of King George V's own Bengal sappers and miners. The graves of the cavalry of the Sudan Defence Forces are marked with their striking badge showing a mounted camel trotting into battle.

The exhausting campaign in North Africa was simple but brutal.

The forces of Britain's Empire pushed the axis armies westward along the great coastal highway that runs the length of the southern shore of the Mediterranean.

The mission was to drive them away from Egypt and the Suez canal, that vital artery that connected Britain to India. The Middle East was the hinge of Empire.

It was a draining and dangerous war.

Veterans remembered flies seething and swarming on every inch of skin, living and dead, crawling into your nose when you breathed and into your mouth when you tried to eat.

You expect to find here the graves of drivers and sappers, troopers and stokers, havildars and sepoys. There are highly-decorated senior officers and sergeants in their late twenties and early thirties, the men who bind together infantry regiments in battle.

But this was a huge and complex modern army raised to fight the fastest-moving and widest-ranging war in history and the headstones tell the stories of other men who brave the fighting alongside them.

British troops race to capture a German tank in Libya, circa 1942

John Fernandes was a butler in the merchant navy but his butling days were done after the fighting. Henry Walpole, a supply assistant, filled in his last form and lifted his last crate somewhere here too.

And who knows what reserves of nerve and loyalty sustained Fateh Muhammed of the Indian General Service Corps. His headstone says simply that he was a water carrier.

My eye was drawn to the graves of another group of non-combatants - men from the British merchant navy who died when their ship, the Ocean Voyager, was torpedoed in Tripoli harbour where it exploded and eventually sank.

They were donkey men and greasers - the men who manned the crane that loaded and unloaded the ship often under enemy attack.

The Voyager was loaded with high-octane fuel and ammunition when it was hit - the survivors of the attack worked with extraordinary bravery to save the ship and rescue their injured shipmates from the flames.

Among the men they could not save, the grave of Cornelius O'Shea perhaps stands out. He was 65 years old, unimaginably ancient to the young soldiers amongst whom he lies.

Here and there you find personal inscriptions whose brief words can hardly bear the weight of the sadness they carry.

You feel you know Flight Sergeant RHJ Harris a little because his mum and dad chose to record that he kept a straight bat and played the game.

And something of the anger towards the enemy and the grim determination that we don't talk about much anymore in the inscription for Lance Bombardier GWS McDonald which says: "I gave my life at 21 to beat the Hun."

There is a similar story of love and loss and anger and grief for every headstone of course, but it's the sheer scale of the suffering which stays with you - and don't forget a similar story could be told from any war grave anywhere on earth.

In all the history of conflict though, there has been nothing, thank God, to compare to World War II - no mosaic so complex or so costly was ever built, nor one that contained so many pieces.

Truly something worth remembering.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00.

Listen online or download on the From Our Own Correspondent downloads page

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday - Friday - see World Service schedule.