Has the Mormon mystique been lifted?

- Published

He didn't win, but Mitt Romney wasn't far off. So what happened to the predictions that a Mormon candidate could never have a shot at the US presidency?

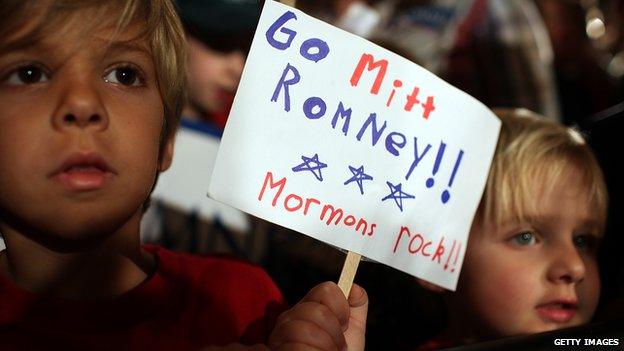

The long lead-up to the US election was peppered with commentaries on Mormonism - the little-understood religion of Mitt Romney, front-runner for the Republican ticket.

The naysayers, external said a Mormon could never win the White House, and they appeared to be backed up by surveys of public opinion.

In June, a study by Gallup suggested that almost 20% of Americans, external would not vote for a well-qualified candidate if he was Mormon - a figure virtually unchanged from 44 years ago, when Mitt's father, George Romney, ran unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination.

Another study by Pew, external found a third of Mormons themselves said they did not feel the country was ready to elect a Mormon president, such is the discrimination against them.

But one person may have got it right: "I don't think, in the final analysis, that religion is going to play a big factor," said Mitt Romney in an interview in January 2012, external.

Although he was trounced in the end in the electoral college vote, he was only a couple of percentage points behind Barack Obama in the national popular vote, and the group deemed by so many pundits to be a write-off for him - evangelical Christians - voted overwhelmingly in his favour.

Exit polls, external suggest that 79% of evangelicals voted for Romney - higher than the percentage of Mormons who voted for him, and more than voted for John McCain four years ago.

"Mitt Romney has opened doors. He has made Mormonism much more respectable," says Charles Dunn, a professor at Regent University, and author of numerous books on politics and religion.

"He came out of this campaign as an honourable person, and that bodes well. He is the best missionary Mormons could have."

At the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the official name of the Mormon Church) in Salt Lake City, Utah, there appears to be a similar mood of optimism. Although they have not given figures on whether membership numbers are up, enquiries certainly are. Mormons make up about 2% of Americans, but numbers are rising steadily.

"Without question there has been an increase in the interest in the Church in the last year," says spokesman Michael Purdy.

There have been more than 100 visits to Salt Lake City by media outlets from around the world, Purdy says. Hits to various Mormon websites are up, and they are dealing with dozens of enquiries every day.

"As far as world attention on Mormonism goes, it's huge," says Scott Gordon, a former Mormon bishop and president of the Foundation for Apologetic Information and Research, which aims to counter misinformation about the Church.

"Before the whole Mitt Romney thing, people would typically ask us almost immediately about polygamy," he says, recalling a number of occasions over the years when he has been asked how many wives he has. At school, the question would be: "How many moms do you have?"

"I think people have finally picked up on the fact that mainstream Mormons are not polygamous."

In his opinion, Romney not winning "is the best of both worlds". It has got people talking about the Church and given Mormons a chance to explain their faith to the world, he says, but spared Mormonism the flak that might have come had Romney won and implemented unpopular policies.

When he ran for the nomination in 2007, Romney decided he had to tackle the perceived "Mormon issue" head-on, and he gave a detailed speech, external on his faith, which many compared to that made by John F Kennedy in 1960, external, at the time when a Catholic running for president was similarly controversial.

This campaign however, Romney remained for the most part studiously quiet on the issue of his faith, right up until the latter stages, when he invited some journalists, external to attend a Sunday service. At the Republican National Convention he touched a little on his faith, as well as having fellow Mormons take the stage with stories of his good work in the Church.

"I wish he would have talked about it more, but I understand why he didn't," says Gordon.

"Those Mormons who have been successful have learned not to talk about Mormonism - you don't want to go through life having to explain things all the time. You want to be judged on your merits - judged on what you do."

A survey in June suggested that as many as 40% of Americans didn't even know Romney was Mormon, external (it should also be noted that a survey at the same time found only one-third of Americans correctly identified Obama as Christian, external).

But some have argued that by largely fencing off his religion, Romney was left dehumanised in the eyes of voters, and unable to be truly himself - and ultimately that served him badly.

Dave Mason, author of My Mormonism: A Primer for Non-Mormons and Mormons Alike, is pleased that Romney didn't win - because he doesn't agree with his policies.

"It did feel like Romney was trotted out like an icon of how we are, and that's very hard to take, when I'm very much not," Mason says.

"I'm not particularly political, but I've gotten more political the last couple of months trying to defend my Mormon identity."

Roughly one in five Mormons did not vote for Romney, and Mason resents the way Mormons are often assumed to be conservative in their political views.

He supports gay marriage, for example, and Obama's healthcare programme, and says these opinions stem from his interpretation of Mormon values.

"I think Romney is a perfectly legitimate Mormon - he's just as Mormon as I am. But it doesn't require us to think the same way about anything," he says.

Indeed, this campaign saw some Mormons actively campaigning for the Democratic Party - for example LDS Dems, which formed in Utah in last year.

And there were evangelical Christians who, despite voicing unease about Romney's religion, actively campaigned on his behalf, finding common cause on social issues such as his stance on abortion and gay marriage.

Among his unlikely supporters was the influential pastor Rev Robert Jeffress, of the First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, who repeatedly referred to Mormonism as "a cult", but who endorsed Romney and encouraged his congregation to do the same.

Jeffress says many pastors and evangelicals across the country struggled with Romney's Mormonism. It was a strategic alliance - "the lesser of the evils", he has said.

Jeffress remains as strident as ever in his criticism of the faith, calling it "a very strange religion".

One theory doing the rounds is that - although the evangelicals who did vote chose Romney - there is a contingent who simply couldn't bring themselves to vote for a Mormon and stayed home, pulling down turnout and possibly proving decisive in some key swing states.

But there doesn't seem to be any evidence for this, says Joe Lenski, executive vice-president of Edison Research, the company that provides exit poll data to the major US news organisations and networks.

The turnout amongst evangelicals nationally appears to be exactly the same as in 2008, he says, at 26% of the electorate.

The exit poll data suggests some variation state-by-state - it was down in Virginia and up in Iowa, for example - but the overall picture is one of a broadly steady evangelical turnout.

"We have entered a new phase - it's now a place where the lines of deep difference lie with those of belief, and those without belief," says Gary Marx, who worked as an adviser to Romney in 2008, and is now executive director of the Faith and Freedom Coalition, a evangelical group that worked at the grassroots level to get the Republican vote out.

"This particular candidacy has bridged that divide," says Marx.

In the 1960s it was seen as a breakthrough to have a Catholic as president

In some ways, it is an alliance between rival religions. Mormons regularly send missionaries to try to convert evangelicals, says Prof Charles Dunn, whilst evangelicals send missionaries to Utah and other areas with high Mormon populations.

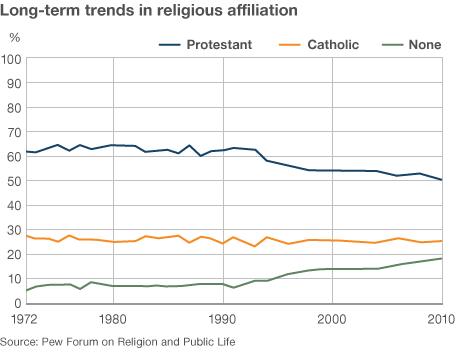

But religion looks set to play a smaller part in future US elections, as the non-religious section of the population grows in size. One-fifth of Americans now say they are not religious. Among young people, it is one-third.

In 1960, John F Kennedy, a Catholic, won the presidency, and Catholicism has not been an issue since. Both vice-presidential candidates this year were Catholic, for example, and no-one batted an eyelid.

And the Mormonism of any future candidate would be a total non-issue, predicts Dunn.

"It's people like Kennedy and Romney who plough the ground, so that others can run the ground. They are the forerunners - the Mormon and the Catholic doing the same thing for their respective religious faiths."

Jon Huntsman, another Mormon contender for the Republican nomination, could be the first to put that theory to the test in 2016.