Enrico Dandolo and the way history overlooks disability

- Published

For a long time there has been Black History Month, but now similar efforts are being made to highlight people with disabilities. So who are the disabled figures in history that we should know more about?

In a museum in Venice stand four remarkable horses made of copper.

A thousand miles away in the magnificent former church of Haghia Sophia in Istanbul, there is a plaque on the upper gallery bearing the name Henricus Dandolo.

This plaque marks the probable site of the tomb of the man who looted those horses in 1204, better known to history as Enrico Dandolo.

Doge of the Republic of Venice from 1192, Dandolo led the Fourth Crusade - an expedition intended to conquer Muslim Egypt - to Constantinople. His armies smashed the heart of the Christian Byzantine Empire.

Dandolo was a dynamic leader, reorganising the Venetian currency and beginning the first codification of the republic's laws.

On the battlefield he was an inspirational figure. When the crusader fleet faltered under a withering hail of arrows from the Byzantine defenders, he was the leader who drove them on.

They became the first foreign force to breach the walls of Constantinople. Dandolo died after campaigning in Bulgaria the following year.

To his supporters, he was brave, forceful and vigorous. To his enemies, ambitious, cunning and unscrupulous.

But there are two facts about Dandolo that are likely to surprise the modern reader.

He achieved all this when he was in his 90s. And he had been blind for more than two decades.

Dandolo went blind in his 60s after a severe blow to his head caused damage to his brain, says Prof Thomas Madden, author of the definitive biography.

Dandolo wasn't the only disabled warrior in the Middle Ages. King John of Bohemia died on horseback in the thick of the Battle of Crecy against the English, having been blind for over a decade.

And the Ridley Scott film Kingdom of Heaven portrays the life of Baldwin IV, king of Jerusalem, who was debilitated by leprosy but still able to win a massive victory against Saladin at the Battle of Montgisard in 1177.

But Dandolo is one of a long line of historical figures whose disability is, in a sense, overlooked.

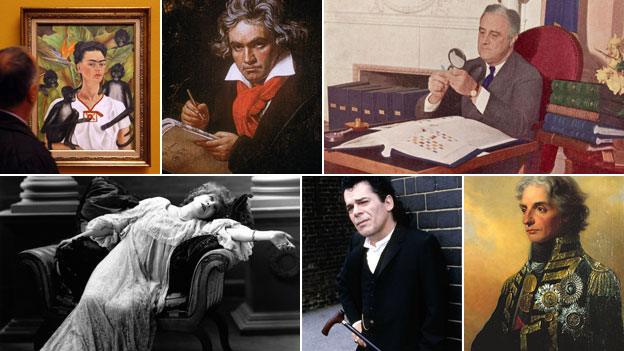

Many will know about Beethoven's deafness, or be aware of the seizures of Julius Caesar - possibly due to epilepsy. The Madness of King George III has been established for posterity by a play and movie. Joanna the Mad of Castile was a key figure in the struggle for control of 16th Century Spain.

Then there is Lord Nelson's disability. The loss of his right arm might have caused the curtailment of his career. It prompted him to write: "A left-handed admiral will never again be considered as useful, therefore the sooner I get to a very humble cottage the better, and make room for a better man to serve the state."

And yet there is a perceptional gap. People do not always think of Nelson, or these other figures, and think of them as "disabled". Few children are taught about the plethora of disabled people in history.

"They are overlooked for two reasons," says sociologist Tom Shakespeare, author of Disability Rights and Wrongs. "Either they are genuinely obscure, or they are not obscure at all but they are not thought of as disabled."

The concept of disabled people as one identity is comparatively recent, says Shakespeare, who writes a blog picking out disabled figures from history, external.

"The word 'disabled' used to describe the whole gamut is a 20th Century thing.

"Disability is very associated with being 'rubbish'. When you get somebody like Dandolo then they are given a kind of honorary non-disabled status. If they are so successful they can't be disabled. That aspect of their identity is not prioritised."

And of course there was always an incentive for disabled people to downplay or even hide their disability.

So it was with Dandolo. "There were stories that he would hide his blindness. He would put a hair in his soup and loudly complain about it," says Madden.

Dandolo's efforts to hide his disability foreshadow those of US President Franklin Roosevelt more than seven centuries later.

Paralysed from the waist down for more than a decade before becoming president, Roosevelt also made great efforts to hide his disability.

There are a handful of images of Roosevelt standing while president, but in every one he is carefully propped up against something.

Roosevelt guessed that knowledge of his disability would harm his electoral prospects.

"How could you be the leader of the free world and disabled?" sums up his attitude, says Shakespeare.

His appearances at speeches and rallies, and in the news media, were carefully choreographed so his wheelchair was never seen.

Here you can see Franklin D Roosevelt propping himself up while standing, and sitting down when meeting people

"There are no cartoons of him as disabled. There is no news reel footage, which is quite extraordinary," says Shakespeare.

Now people are aware of Roosevelt having been in a wheelchair. It made for a pivotal scene in the movie Pearl Harbor.

In the case of Dandolo, it is easy even for modern students to forget the level of his impairment. "I've never really thought about him as 'disabled'," admits Madden.

He is shown a number of times in the illustrations on the magnificent Chamber of the Grand Council in Venice. But you wouldn't necessarily guess his blindness from the paintings.

"It shows a very vigorous man looking at things and doing things," says Madden.

"None of the depictions include people leading him around and showing him places. It was always just this very powerful man."

In the modern mind, such extraordinary success for a person with a particular disability would be a reason to espouse optimism about the potential of all people with that disability. The medieval mindset was different.

"Venetians in the medieval world would see the blindness purely as a deficit. There is no way they would see this as a victory [for a disabled person]," says Madden.

But there is a glorious irony in the life of Dandolo. The Byzantine Empire often blinded its deposed emperors in the belief that would preclude them from retaking power, yet it was eventually toppled by a blind enemy.

Of course, history is not all a story of "great men".

The lives of ordinary people, and the social and legal landmarks, are what many disabled people will look back on as important.

But there is emblematic purpose in picking out disabled figures from history, says Shakespeare. "It is very important to name people because we have such a negative view [of disabled people]."

There might be a useful lesson in the Mary Seacole effect. Seacole - a contemporary of Florence Nightingale - is now a well-known and celebrated figure, having descended into obscurity for over a century at least in part due to racial prejudice.

The reestablishment of Seacole as a major figure is still an important landmark for black history.

Disability History Month may soon achieve the same.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external