How might one brush up on British history's Christian bits?

- Published

A survey has suggested that many people believe the children need to learn about Christianity to understand English history. But which bits of religious education do people need to brush up on to make sense of English, and indeed British, history, asks Stephen Tomkins.

Here is a brief revision guide for the uninitiated.

1. The Papacy

The differences between Catholics and Protestants are many and complex, but the vital one for British history is that the Pope has absolute authority over the Catholic Church, while Protestant churches are free to work things out for themselves.

Before the Reformation, the church was a central part of British society governed by a foreign ruler, so many conflicts revolved around papal authority, including the one which culminated in the murder of Thomas Becket.

Come the Reformation, it was the chance to increase his own power at the expense of the Pope's that persuaded the ardently Catholic Henry VIII to break with Rome.

After this break with papal absolutism, civil liberties such as freedom of speech were developed and marketed as "protestant freedoms".

Opponents of Catholics regarded them as answerable to a foreign ruler, which led to ingrained hostility in the UK for centuries. They were viewed by some as being politically as well as spiritually suspect.

Extra tip: Impress the examiners by mentioning that for two centuries it was the Pope rather than Guy Fawkes who was burned on Bonfire Night.

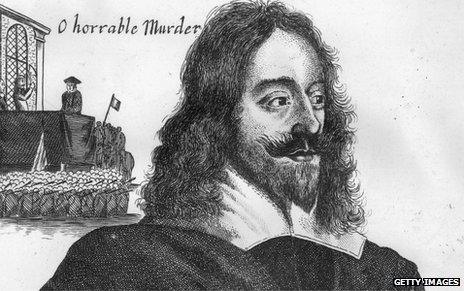

2. Divine rule

Charles I defended to the scaffold his belief in divine rule

It seems obvious to us today that we should choose our own leaders and laws.

But in the Bible, God chose kings for Israel and wrote the law of the land, and political thinkers throughout much of British history believed their rulers and rules were also given by God.

This helps to explain why it was such a long struggle for parliamentary democracy to develop, and the righteous fervour of defenders of royal power such as Charles I and the cavaliers.

Extra tip: For full marks, note that this was - originally at least - a progressive idea. In the Middle Ages, the belief that the law is from God led to the principle, enshrined in Magna Carta, that the king is subject to it. The king does not impose his law on his people, God imposes his law on his people, which includes the king as much as anyone.

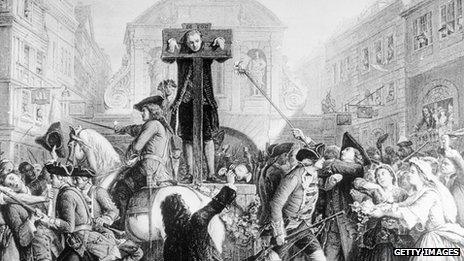

3. Uniformity

Writer Daniel Defoe was pilloried for his dissenting views

Living in today's pluralistic society, it is hard to grasp how obvious it was to most British people until 300 years ago that the country should be united in one religion - as obvious as it is to us that we must all be subject to the same laws.

Religious dissent threatened the whole fabric of society. This accounts for assaults on unsanctioned religions, from state executions of Protestants under Queen Mary, to mob attacks on Quakers and Baptists in the Restoration.

Extra tip: Dazzle the examiners by using the phrase "cuius regio, eius religio" - whoever's realm, his religion.

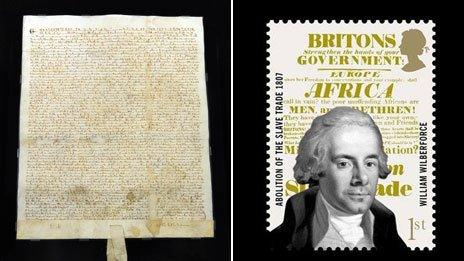

4. Image of God

"The image of God" influenced Magna Carta and the abolitionist movement

Perhaps the most influential passage of the Bible in political history is one which could hardly sound less political - the creation.

Genesis says that man and women were made "in the image of God". Ever since this idea made Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome, outlaw facial branding, it has made the value of every individual a recurrent feature of political debates.

It informed medieval restrictions on royal power, the Peasants' Revolt, the British enlightenment, the anti-slavery movement and the Labour movement.

5. Heaven and hell

Again it's hard to grasp what a solid reality the afterlife was to most British people before the 20th Century. But without this, the sheer amount of time devoted religious debates, conflicts and movements throughout history is baffling and inexplicable. It mattered whether or not your religious pursuits were going to save your soul.

Hence the passion of the debate between puritans and Arminians over such issues as whether vicars should wear robes, which helped feed the flames of the civil war that led to the execution of the King.

Hence also the self-sacrificial drive of British missionaries in Africa, who inadvertently laid the foundation for imperial expansion there.

It explains why Queen Mary was willing to burn 300 people who promoted the wrong faith, and why John Wesley rode over 250,000 miles round Britain in the evangelical revival.

Extra tip: Why not round off your essay with a quote from Charles I - "I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown".

Stephen Tomkins is the author of A Short History of Christianity