Mathias Rust: German teenager who flew to Red Square

- Published

In 1987 a West German teenager shocked the world, by flying through Soviet air defences to land a Cessna aeroplane in Red Square. He was jailed for more than a year - but a quarter of a century later, he has no regrets.

Exactly 25 years ago, the USSR Foreign Ministry announced that it had rejected an appeal by a German teenager against his prison sentence.

Mathias Rust, just 19, had single-handedly flown more than 500 miles (750km) through every Soviet defensive shield in a single-engine plane to land at the gates of the Kremlin.

The idea had come to him a year earlier while he was watching TV at his parents' home where he lived in Hamburg, West Germany.

A summit between the US and Soviet presidents in Reykjavik had ended in a stalemate, and the teenager who had a passion for politics felt he wanted to do something to make a difference.

Rust was sentenced to four years in a labour camp

"I thought every human on this planet is responsible for some progress and I was looking for an opportunity to take my share in it," he says.

Rust already had a pilot's licence and had clocked up 50 hours in the air when it occurred to him to put his skill to use.

"I was thinking I could use the aircraft to build an imaginary bridge between West and East to show that a lot of people in Europe wanted to improve relations between our worlds."

Many idealistic teenagers may have had similar fantasies of bringing about world peace by performing daring acts. The difference with Rust is that he actually went ahead with his plan.

On 13 May 1987 he told his parents he was going to tour northern Europe in a Cessna airplane, in order to clock up hours towards his professional pilot's licence.

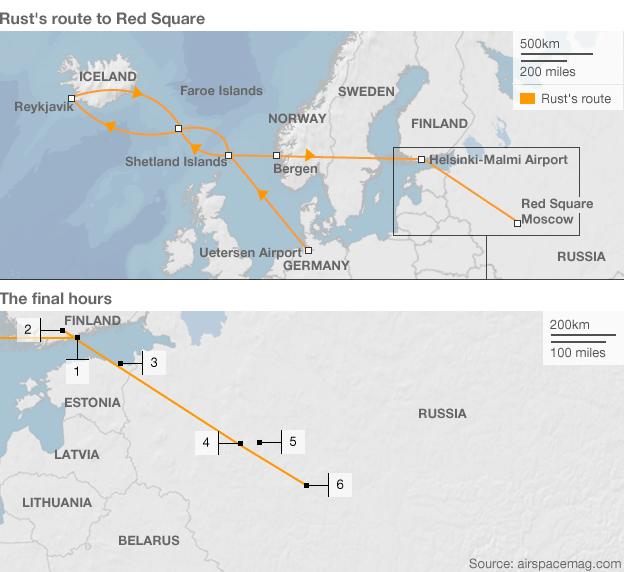

His first stop was in the Shetland Islands, then the Faroe Islands. He spent one night in each.

Next came the capital of Iceland, Reykjavik, then Bergen in Norway before he arrived on 25 May in the Finnish capital, Helsinki.

He spent several days there trying to decide if he really had the courage to go through with his plan. He had good reason to be nervous.

Archive footage of Mathias Rust landing in Red Square

The USSR had the largest air defence system in the world. Less than five years earlier, a South Korean civilian airliner had been shot down after straying into Soviet air space, causing the death of all 269 passengers on board.

"Of course I was afraid to lose my life," Rust recalls.

"I was weighing if it is really responsible, reasonable, to take this kind of risk. At the end I came to the conclusion, 'I have to risk it.'"

On the morning of 28 May, he told air traffic control in Helsinki he would be heading to Stockholm, in Sweden. Even then he wasn't completely sure he would go through with it.

"I made the final decision about half an hour after departure. I just changed the direction to 170 degrees and I was heading straight down to Moscow," he says.

Back in Helsinki, operators at air control began to worry. Rust was heading in the wrong direction and then vanished from their radar screens before they could make radio contact.

An enormous manhunt was launched by the Finnish coastguard and when a patch of oil was spotted on the sea surface, divers were brought in to search for a wreck.

While they were hunting for him, Rust was sitting snug in his cockpit as his plane crossed into Soviet airspace, over Estonia.

Within minutes he had been picked up by Soviet radar, and less than an hour later a MiG fighter jet approached him.

"It passed me on my left side so close that I could see the two pilots sitting in the cockpit and I saw of course the red star of the wing of the aircraft."

Rust was terrified, but instead of attacking him, the jet passed by and disappeared into the clouds.

A combination of unbelievable luck and human error had led to Rust's plane being mistaken for a friendly aircraft.

A plane crash the previous day, and an ongoing rescue operation, along with training for new pilots had led to confusion in the air and in control centres.

Somehow Rust managed to make it hundreds of miles across Soviet airspace to the capital without any further contact from USSR defence forces.

"I couldn't believe I actually survived," he recalls.

"I had calculated at the time that my chances of survival were about 50:50 and after I reached my destination, I knew that I really was on the lucky side."

But his relief at seeing the spires and domes of Moscow quickly faded when he realised that landing was going to be difficult.

He had wanted to bring down the plane in the middle of Red Square in order to make a big statement but the landmark was packed full of people.

On the ground, Soviet citizens were stopping and looking up in amazement as the small white plane circled just 30 ft (10m) above the ground.

Finally Rust spotted a four-lane bridge next to St Basil's Cathedral so he circled around one more time and touched down there.

Later, when he was questioned by the Russian police, he learned that the bridge was usually spanned by thick cables, which would have made a landing impossible.

By chance, they had been removed from the bridge that very morning for maintenance.

"The police presumed that I had co-operators in Moscow who had arranged it so that I would be able to land," Rust says.

At around 19:00, just as the sun was going down, Rust taxied his plane into the square and climbed out of the cockpit to greet the crowds which gathered around him.

They wanted to know where the young foreigner was from and why he was there.

"I am here on a peace mission from Germany," Rust told them.

When they shook his hand, glad to meet an ally, he had to explain that he came from "the other Germany", West not the Communist East as they presumed.

Dr Robin Stott, a British doctor who happened to be in Moscow as part of an anti-nuclear pressure group, was taking time out from a non-proliferation conference to see the sights when Rust landed his plane right in front of him.

"It was an extraordinary thing. None of us had a clue what was going on," he recalls.

He now works as yoga instructor and financial analyst

"Everyone around him was very impressed; even the security services kept saying what a brave boy they thought he was."

Once the police had recovered from the shock of finding an unauthorised aircraft parked at the gates of the Kremlin, Rust was arrested.

He spent hours trying to persuade the authorities that he had acted alone and was not part of some sinister plot hatched by foreign governments.

In the Kremlin there was shock and plenty of red faces as the full extent of the humiliating incident became apparent.

But it is likely that President Gorbachev realised he could use the opportunity to his advantage to rid himself of military officials whom he saw as standing in the way of his reforms.

Within a couple of days the minister of defence had been forced to retire, and the head of the air defence services had been sacked. Over the next few months more than 150 people lost their jobs.

Rust was charged and pleaded guilty to violating international flight rules and illegally crossing the Soviet border. After some confusion in court he pleaded not guilty to "malicious hooliganism".

The judge sentenced him to four years in a labour camp for what he called an act of adventurism.

Despite being allowed to serve his time in Lefortovo prison in Moscow, Rust took his confinement badly.

"It was really hard for me being just 19 years old to just be locked up for 23 hours a day. I had a lot of difficulty keeping food down and I lost a lot of weight," he says.

Then in 1988, following the signing of a non-proliferation treaty by Reagan and Gorbachev, Rust was released as a gesture of good will after serving only 14 months.

Rust's flight was seen as so incredible to Muscovites that it wormed its way into popular culture. For a while Red Square was jokingly referred to as Sheremetyevo-3 - Sheremetyevo-1 and -2 are airports near Moscow.

Within a year of returning to Hamburg, Rust stabbed a colleague at a hospital where he worked and ended up behind bars again.

Today he makes his living as a financial analyst and a yoga instructor.

He says he has no regrets about what he did and believes he had a hand in helping President Gorbachev with his reforms.

"I am very convinced that I enabled him to push through his Perestroika and Glasnost much faster than he would have done without me."

Chloe Hadjimatheou's interview with Mathias Rust was broadcast on the BBC World Service's Witness programme. You can download a podcast of the programme or browse the archive.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external