What is a quintessentially British park?

- Published

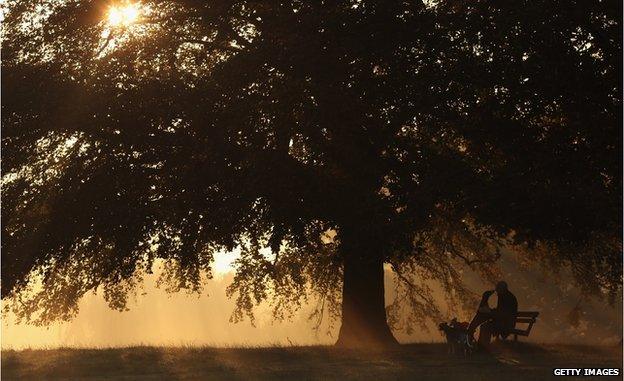

Campaigners complain cuts to park budgets risk damaging the fabric of green spaces inherited from the Victorians. But what is the classic British park? And why should they be protected?

Picture any city in the world, and it is likely to conjure up an image of a park.

Central Park elicits indelible visions of Manhattan. Paris makes the Bois de Boulogne spring to mind. Barcelona has Gaudi's Park Guell.

Birkenhead Park was one of the UK's first publicly funded civic park in 1847. Three years later an American visitor was awestruck by what he saw.

"Five minutes of admiration, and a few more spent studying the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty, and I was ready to admit that in democratic America there was nothing to be thought of as comparable with this People's Garden," landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted later recalled in a book.

He took his experience away with him and built Central Park. Arguably the world's most famous, enshrined in a thousand films, it has British park DNA.

Like Birkenhead, many of the UK's greatest parks are Victorian in genesis. This was a time of civic initiative.

A generation inspired by countryside-obsessed Romantic poets conjured up oases of greenery at the heart of the smog-choked cities made fat by the Industrial Revolution.

Parks were places to promenade. Landscape design was an enviable profession.

The period saw the creation of famous parks such as Liverpool's Sefton Park, Birmingham's Handsworth Park (formerly known as Victoria Park) and Sheffield's Endcliffe Park and Botanical Gardens.

For many people London's Hyde Park - which started life as a deer park after Henry VIII confiscated it from a monastery, and was first opened to the general public by Charles I in 1637 - is the quintessential British park. It is certainly the most famous of the capital's eight Royal Parks, which cover 5,000 acres in total.

Of course plenty of parks have distinctive features, such as Edinburgh's Holyrood Park, with its array of hills, lochs, glens, ridges and basalt cliffs, as well as Arthur's Seat, one of four hill forts. Cardiff's Roath Park, with its Scott Memorial Lighthouse, on the lake, is often pictured on postcards of the city.

Royal Parks and Victorian parks share similar characteristics. These add up to what people tend to think of as the quintessentially British park, says David Tibbatts, business development manager at Greenspace.

Hope Street Park in St Anne's-on-Sea

"It's a large, designed landscape, usually inherited from someone's magnificent home. It normally had a deer park, or hunting ground at its origins, and often contains feature-rich structures such as lodges, gatehouses, ice houses and fountains.

"These parks are essentially beautiful. They were designed to please a cultured eye, and were meant to be a glorification of God's nature. People were meant to be awestruck by the standard of maintenance and care, the refinement of the planting, the heightened landscapes, and the finest horticultural standards," he says.

Of course not all parks are of this pedigree. But Tibbatts believes people would be surprised by how many British parks contain classic features, such as ornate railings, fine entrance points and avenues of trees, even in much smaller urban spaces.

The proliferation of public park tennis courts, bowling greens, boating lakes and toilets also came from this period, he says.

Subsequent generations have created parks with different influences and designs, with projects like the Mile End park, in Tower Hamlets - which was constructed on parcels of land, and is bisected by roads and railway lines - in many ways the ultimate modern 21st Century park.

It has, among other things, a "play arena" for children, an "ecology park" - which includes a lake, wind turbine and climbing wall - an arts park and a sports park.

However demands on urban space mean Victorian parks will always be exceptional for their size, and the modern business of promoting and supporting parks has often been much more about maintaining that Victorian legacy than creating new ones.

Many around the UK will walk out on a cold, crisp day this Christmas for a walk around their local park. But in a time when English councils are facing funding cuts, should parks still be protected?

In the 1970s and 1980s, parks slipped down local authorities' agenda. A lack of investment, and concerns over anti-social behaviour, littering and safety, meant many parks became bleak no-go areas.

Then green campaigners upped their game, producing research to suggest that well-managed parks were good for everything from health and social cohesion, to reducing crime and boosting property prices.

"The 1990s saw a revolution. Suddenly parks gained prestige, they got a career boost. Everybody got fed up with derelict, grim parks and closed cafes. Local authorities, which had been pouring money into leisure centres, suddenly started more pride in parks," says Ken Worpole, who was on the government's Urban Green Spaces Task Force in 2001.

He says the Heritage Lottery Fund - which has spent £640m on regenerating and revitalising 700 parks around the UK since 1996 - and the introduction of the Green Flag Award, which wanted to do for parks what the Blue Flag did for beaches, also had an impact.

There were seven Green Flag Awards in 1996 and 1,424 in 2012.

Local residents, which have a vested interest in keeping their parks pristine, have also become increasingly active. There are now 5,000 local Friends Groups - which work with local authorities - in the UK.

With spending squeezed, Worpole thinks park maintenance may have to be thought about differently, but he says local residents are already taking on some of the responsibility themselves.

"Communities want a feeling of security, but also stewardship," says Worpole. "It means were are seeing different things happening in parks, such as food growing, and allotments, more cafes where people can get a coffee - they are getting together on issues that we would normally call customer service."

Drew Benellick, who is in charge of parks at the Heritage Lottery Fund, agrees engaging people with their local parks is just as important as conservation and providing new facilities.

"If you repair a bandstand, but don't teach people the value of it, it can be re-vandalised within weeks," he says.

He cites Myatt's Fields Park, in Lambeth, south London, as a lovely little park that has seen put the community at the heart of its regeneration.

"There are greenhouses for growing food, which they partly sell, and partly use in soups. There is a baking group. It is in a part of London that is a cultural mixing pot, and they are really imaginative. They put on Afro-Caribbean nights, Indian-themed nights," he says.

Everyone should have a good quality green space within a five minute walk of their home, as evidence suggests some people further away won't travel, says Paul Todd, manager of the Green Flag Award scheme.

It is estimated that there are 2.5bn visits to public parks in the UK every year.

People still want green and pleasant land.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external