How Paraguay's 'Archive of Terror' put Operation Condor in focus

- Published

Twenty years ago Paraguayan lawyer Martin Almada got a tip-off that would change his life and help expose a vast operation run by South American military dictators to crush their political opponents.

He had been searching for 15 years for documents that would enable him to prove he had been tortured by the military dictatorship of Gen Alfredo Stroessner in the 1970s - and that his wife had been forced to listen to recordings of his ordeal.

Now, three years after Stroessner's downfall, a woman on the other end of the phone was telling him she knew where to find them.

"I told her to come over here and she brought a sketch map," Almada recalls. "She handed it over and said she trusted me to act on it."

Within days, Almada and a collaborator, Jose Agustin Fernandez, had travelled to the spot marked on the map - a run-down police station on the outskirts of the Paraguayan capital, Asuncion.

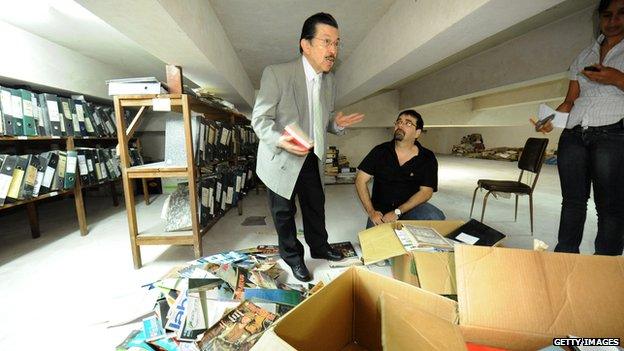

"This was a completely normal police station," Almada says. "In the yard, there was a bakery, some workshops and, at the very back, a building containing a mountain of papers - an absolute mountain of papers."

In fact, there were about 700,000 documents forming a complete record of the activities of the Paraguayan secret police over three decades - a cache that became known as the Archive of Terror.

For Almada, the papers would show doubters once and for all that he was telling the truth about his experiences as a prisoner in Paraguay between 1974 and 1977.

"I cried with joy, because people used to treat me as though I was making up everything I saw," he says.

"It was like an explosion of memory.

"I felt that each folder we opened up would help us go back to the past and understand the regime of terror which we suffered. Every document revealed terror and tragedy."

Stroessner ruled Paraguay for 35 years with the help of the army and the secret police, after seizing power in 1954.

Using a network of informers, the authorities pursued any Paraguayan considered subversive - including teachers, peasant activists, or priests who advocated social change.

The secret police were led by the feared Pastor Coronel, who is said to have tortured suspects personally. But he had an Achilles heel - his obsession with orderly paperwork.

His officers carefully noted every arrest, every interrogation, and every movement of a suspect. They also made hundreds of recordings of opposition meetings and photographed suspicious activity.

The Archive of Terror contains photographs taken with telephoto lenses of Paraguayans at funerals and weddings. The secret police even noted the number plates of cars parked near meetings of the clandestine opposition.

Almada came to the attention of the secret police in the early 1970s, when he and his wife, Celestina, were working as teachers in a school they had set up on the outskirts of Asuncion. Their politics were left-wing, and they campaigned for better salaries and working conditions for teachers, and for changes to the curriculum.

One evening, the secret police came for him.

After 30 days of interrogation, Almada was officially classified as an "intellectual terrorist and an ignoramus". He was sent to the infamous Emboscada open-air prison where he was held for three years.

There, he tried desperately to get news about his wife.

Celestina had died shortly after Almada's arrest in what the police said was a suicide. Almada has always believed she died because police played her recordings of him being tortured.

"The telephone was used as an instrument of psychological torture," he says. "For eight days, they made her listen systematically to everything that happened to me. Then they sent her my bloodied clothing. Finally they called her one night and said, 'The subversive teacher is dead, come and get his body.'"

"She died of a heart attack," he says. "She died of grief."

Almada scoured the recordings in the Archive of Terror, hoping to find a tape of the police contacting his wife. But although he found his own personal file, there was nothing that explained Celestina's death.

Almada did find answers to another question that had obsessed him.

While in detention, Almada had met inmates from other South American countries who talked about a secret operation by Paraguay and the other dictatorships in the region to co-ordinate intelligence and return political prisoners to their home country. It seemed to be codenamed Condor.

"I'd heard about Operation Condor when I was in the belly of the condor itself," says Almada.

In the archive, Almada and Fernandez found a vital document. Marked Top Secret, it is an invitation from the head of the Chilean secret police to his Paraguayan counterpart to attend the founding meeting of Operation Condor in Santiago on 25 November 1975.

"It is crucial and the key document," says Andrew Nickson, a British academic who once worked for Amnesty International in Paraguay. "The Chileans and Argentines would be mad as hell to know that these documents were not disposed of."

Thanks to the invitation and other paperwork in the Archive of Terror, it's now known that Paraguay, Chile, Argentina and Uruguay were the founding members of Operation Condor - with Bolivia and Brazil joining later.

The operation had an encrypted communication system, routed through US military bases in the Panama Canal, which enabled members to build up a database of suspects and respond quickly to sightings.

John Dinges, author of The Condor Years, says the Archive of Terror - along with declassified US files on Chile and Argentina, and other documents at the non-profit National Security Archive in Washington - form the foundation of what is known about the inner workings of the South American security forces in these years.

"Without them the judicial investigations in all of our countries would have had to rely almost entirely on the victim accounts compiled by human rights investigators over the years, and on the good will of the very few military sources who have come forward," he says.

The evidence collected by Almada became an important part of the attempts to prosecute Gen Pinochet of Chile, between 1998 and 2006. The archive has also been used in several key human rights cases in Argentina and Chile.

In Paraguay itself, a handful of torturers have been sent for trial since the return of democracy, but the vast majority of commanders associated with the military government have escaped justice.

Nevertheless, Almada believes he, and not his torturers, has had the last word.

"When I was handcuffed and shackled, I used to say to them that the world was a slowly turning wheel and that sooner or later democracy would come and I would play a very important role.

"I made that up of course, and I doubt they believed me, but in a way it has come true."

Simon Watt's interview with Martin Almada was broadcast on 12 December on the BBC World Service's Witness programme. You can download a podcast of the programme or browse the archive.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external