Queen Victoria: The real story of her 'domestic bliss'

- Published

To the outside world Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their family seemed the embodiment of domestic bliss, but the reality was very different, writes historian Jane Ridley.

The marriage between the two first cousins - the young Queen and the clever, handsome German prince - was a love match. Over 17 years, nine children were born: four boys and five girls.

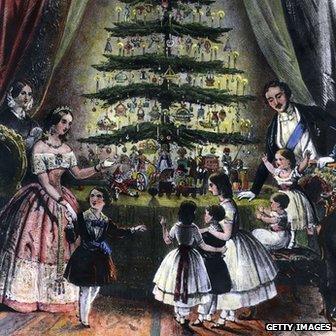

Paintings and photographs projected an image of a virtuous, devoted young couple surrounded by obedient, fair-haired children.

Though sexually infatuated, the young couple were locked into a power struggle. Albert took over more and more of Victoria's work as queen as her pregnancies forced her to step aside. Victoria was conflicted: she admired her "angel" for his talents and ability but she deeply resented being robbed of her powers as queen.

There were terrible rows and Albert was terrified by Victoria's temper tantrums. Always at the back of his mind was the fear she might have inherited the madness of George III. While she stormed around the palace, he was reduced to putting notes under her door.

Though she was a prolific mother, Victoria loathed being pregnant. Repeated pregnancies she considered "more like a rabbit or a guinea pig than anything else and not very nice".

Breastfeeding she especially disliked, finding it a disgusting practice. And she was not a doting mother - she thought it her duty to be "severe". She didn't do affection.

Relations with her eldest son Bertie, later Edward VII, were especially fraught. From the start he was a disappointment for Victoria.

Like all the royal princes, he was educated at home with a tutor. Bertie did badly at lessons and his parents considered him a halfwit. Victoria remarked: "Handsome I cannot think him, with that painfully small and narrow head, those immense features and total want of chin."

When Bertie was 19, he spent time training with the army in Ireland and a prostitute named Nellie Clifden was smuggled into his bed. When the story reached Albert, he was devastated and wrote Bertie a long, emotional letter lamenting his "fall".

He visited his son at Cambridge and the two went for a long walk together in the rain. Albert returned to Windsor a sick man and three weeks later he was dead.

Albert probably died of typhoid. Another theory is that he suffered from Crohn's disease, but for years afterwards Victoria blamed Bertie for his death. She could not bear to have him near her. "I never can or shall look at him without a shudder," she wrote.

For the next 40 years - the rest of her life - Victoria wore black mourning and only appeared in public rarely and reluctantly. To her people, the tiny "widow of Windsor" seemed a pathetic, grief-stricken figure. The truth was very different.

Though Victoria was invisible, her need to control her children was almost pathological. She set up a network of spies and informers who reported back to her on her children's doings.

When Bertie married the Danish princess Alexandra, Victoria instructed the doctor to report back on every detail of her health, including her menstrual cycle. Court balls were scheduled so that they did not coincide with Alexandra's periods.

Victoria's eldest daughter Vicky married Fritz, the heir to the throne of Prussia, when she was 17. She was the mother of Kaiser William II.

Even in faraway Germany, Vicky could not escape her mother's interfering. Victoria wrote almost daily and her micromanaging made her daughter ill with worry.

When Vicky announced she was pregnant, Victoria replied: "The horrid news... has upset us dreadfully".

Vicky and her younger sister Alice, also married to a German prince, colluded to defy their mother. Secretly, they breastfed their babies. When Victoria discovered, she was furious and called them cows.

Prince Albert's practice of putting up Christmas trees at Windsor became well known in the 1840s

Being a daughter of Queen Victoria was like playing an endless game of musical chairs - there was always one who was out of favour. There was always a favourite, too.

Victoria's changes of mind were bewildering and her rages could be terrifying. She was not only her children's mother but also their sovereign and she never let them forget it.

She kept her youngest child Beatrice (known as Baby) at home; she was terrified of her mother.

Victoria wanted Beatrice to remain unmarried. When Beatrice announced that she was engaged to a handsome German prince, Victoria refused to speak to her for six months and agreed only on condition that the couple lived with her.

The rebel was Louise. Flirtatious, attractive and feisty, she refused to marry a German prince. Instead, she chose Lord Lorne, the son of the Duke of Argyll. This turned out to be a mistake - the marriage was childless and unhappy and Lorne was rumoured to be gay.

Victoria controlled her sons just as tightly. Leopold, who inherited haemophilia, suffered especially. Victoria described him as "a very common-looking child".

She tried to make him live the life of an invalid, wrapping him in cotton wool. As a boy, he was bullied by the Highland servant who looked after him, but Victoria refused to listen to Leopold's complaints. She wouldn't let him leave home but he finally won the long battle to study at Oxford. He died aged 30.

Victoria wanted her sons to grow up like Prince Albert. The only one who resembled his father was Prince Arthur, the third of the boys, later Duke of Connaught. He was her favourite - he did what he was told and had a successful military career.

The son with whom Victoria quarrelled most was the eldest, Bertie. She once remarked that the trouble with Bertie was that he was too like her. She was right. Like his mother, Bertie was greedy and highly sexed, with an explosive temper. But he possessed one supreme gift - personal charm.

As Prince of Wales, Bertie lurched from one scandal to another. In spite of his repeated requests, Victoria never allowed him access to government documents.

But the story had an unexpected ending. Bertie never broke off relations with his mother. When he eventually succeeded her as king at the age of 59, he did a very good job.

He modernised the monarchy, which was one reason why the British monarchy survived World War I when so many others did not. Perhaps Queen Victoria was not such a bad mother after all.

Jane Ridley's Bertie: A Life of Edward VII is published by Chatto & Windus. Queen Victoria's Children is broadcast on BBC Two on Tuesday 1, Wednesday 2, and Thursday 3 January at 21:00 GMT

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external