Digital Chinese caves preserve history

- Published

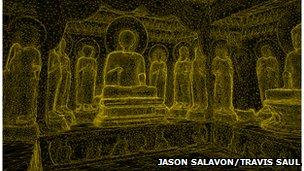

The digital reconstruction of the south cave of Xiangtangshan with the missing fragments shown in yellow and reproduced in their original location

Digital caves are a revelation for tourists - and offer respite for ancient historical sites. Jane O'Brien explores how 3D recreations can be even better than the real thing.

Atmospheric music greets visitors to Cave 220 - part of the Mogau Grottoes of Dunhuang, an oasis on the ancient Silk Road in China's Gobi Desert.

A flickering torch offers a tantalising glimpse of the exquisite murals painted by Buddhist monks some 1,400 years ago. And then suddenly, the cavern is ablaze with light, its beauty fully revealed in dazzling colour and extraordinary detail.

But this is not a real cave - it's a virtual environment created by scientists in Hong Kong using technology that has only been available for a few years.

The result is so realistic that it might become the only way to 'see' endangered historic sites and monuments in the future.

"You wouldn't be able to see any of this in the real cave because light exposure is so damaging," says Jeffrey Shaw, director of Alive, the Applied Laboratory for Interactive Visualization and Embodiment, external at the City University of Hong Kong.

His team created the virtual cave by mapping the original structure using laser scans and ultra-high resolution photography. Many experts say the result is more visually appealing and accessible than the real thing.

"When you show this to an academic they go into a swoon, because as a tool for actually looking at the painting, it's extraordinarily powerful," says Mr Shaw.

Inside the digital reconstruction of the historic caves at Dunhuang

The technology enabled the Alive team to augment reality, enhancing colour and magnifying detail. They are also experimenting with animation: the scarves of Bodhisattvas (enlightened beings) riding elephants flutter in a virtual breeze while dancers spring from the wall and perform movements choreographed by the Beijing Dance Academy.

Musical instruments are magnified and rotate in three-dimensional form while the sound they probably made plays from hidden speakers.

"This project has been driven by the challenges of preservation and conservation," says Mr Shaw.

"The caves are an extraordinary heritage site and under enormous environmental threat, and there is also increasing stress from the number of tourists who now want to visit."

According to the UN World Tourism Organization, a record one billion people will have travelled abroad for leisure by the end of this year. While Europe remains the most visited region, Asia's tourism industry is the fastest growing.

But the human traffic can cause extensive damage to fragile sites, increasing wear and tear through erosion and light exposure.

"The best way to preserve the Dunhuang caves is to close and hermetically seal them," says Mr Shaw. "The idea is that these digital reconstructions will give the viewer an alternative and very strong experience of the caves."

Digital data points are mapped out to form the foundation of the 3D reconstruction of the south cave of Xiangtangshan. (Courtesy of the Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago)

The Mogau Grottoes are a Unesco World Heritage Site, external and represent the greatest collection of Buddhist art from the 4th to the 14th Century AD.

The Dunhuang Academy, external, which promotes and protects the complex of 492 cave temples, is planning to permanently install digital reconstructions of a number of the caves.

Visitors will experience an extensive virtual environment before gaining brief access to one or two of the real caves.

But such technology is not confined to creating or enhancing tourist attractions. Art historians at the University of Chicago have digitally recreated another Buddhist cave temple complex at Xiangtangshan in northern China, where many of the site's original sculptures have been lost or removed.

Katherine Tsiang, associate director of the University of Chicago's Center for the Art of East Asia, external, spent many years travelling around the world to locate the missing sculptures and collect 3D digital images - technology that was not available when she started the project.

"Initially it was matching photos," she says. "But unfortunately these caves were not photographed before the damage began.

They were first photographed in the 1920s when most of the sculptures had been removed."

But advances in laser scanning gave her the breakthrough she needed and enabled her to match many pieces with their exact location in the caves. The results are now on exhibition at New York's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, external.

One display shows a video reconstruction of the sculptures in their original cave settings, which, like the digital Dunhuang cave, gives visitors the illusion of being inside the environment.

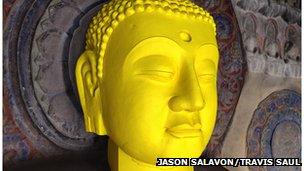

A digital reproduction of one of the missing sculptures. The same information could be used to print a replica on a 3D printer.

"This technology opens up new windows in being able to work with material like this," says Prof Tsiang.

"A lot of reconstruction of sites can be done. And in fact this technology can be used to print 3D models."

That could be good news for China, which has lost many of its ancient treasures to western collectors.

It would be impossible to reinstate the original sculptures of Xiangtangshan, says Prof Tsiang because they are too heavy and fragile.

But an exact replica in lightweight plastic could now be printed by anybody with a 3D printer and the necessary digital data.

Digital mapping is also being used to record objects discovered in new tomb excavations in China.

"Once the objects are removed you lose a lot of information," says Prof Tsiang.

"So much of the meaning of these tombs lies in where the objects are placed and their juxtaposition to one another. Once they're removed, if it's not carefully recorded, that information is lost."

She has been working closely with Washington's Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian Art, external, which has some of the Xiangtangshan sculptures in its collection and collaborated on the restoration project.

The Galleries' Chinese art expert, Daisy Wang says advances in technology represent a new direction for cultural conservation.

"People still think that going to see the real thing is best, but I think digitisation and the way it widens access is the answer to many questions," she says.