The tourists held by Greek police as illegal migrants

- Published

Greek police have stepped up efforts to catch illegal immigrants in recent months, launching a new operation to check the papers of people who look foreign. But tourists have also been picked up in the sweeps - and at least two have been badly beaten.

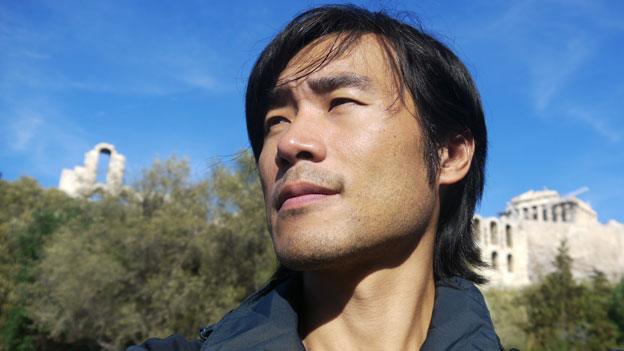

When Korean backpacker Hyun Young Jung was stopped by a tall scruffy looking man speaking Greek on the street in central Athens he thought it might be some kind of scam, so he dismissed the man politely and continued on his way.

A few moments later he was stopped again, this time by a man in uniform who asked for his documents. But as a hardened traveller he was cautious.

Greece was the 16th stop in his two-year-long round-the-world trip and he'd often been warned about people dressing in fake uniforms to extract money from backpackers, so while he handed over his passport he also asked the man to show him his police ID.

Instead, Jung says, he received a punch in the face.

Within seconds, the uniformed man and his plainclothes partner - the man who had first approached Jung - had him down on the ground and were kicking him, according to the Korean.

In shock, Jung was by now convinced he was being mugged by criminals and began shouting for help from passers-by.

"I was very scared," he says.

It was only when he was handcuffed and dragged 500m (500 yards) up the road to the nearest police station that he realised he was actually under arrest.

Jung says that outside the station the uniformed officer, without any kind of warning, turned on him again, hitting him in the face.

"There were members of the public who saw what happened, like the man who works in the shop opposite the police station, but they were too afraid to help me," he says.

Inside the police station, Jung says he was attacked a third time in the stairwell where there were no people or cameras.

"I can understand them asking me for ID and I even understand that there may have been a case to justify them hitting me in the first instance. But why did they continue beating me after I was handcuffed?" he asks.

Jung was held with a number of migrants from Africa and Asia who had also been rounded up as part of the police's anti-immigration operation Xenios Zeus - named, strangely, after the ancient Greek god of hospitality.

The operation aims to tackle the wave of illegal immigration which over the last decade has changed the face of Athens's city centre.

It is thought that up to 95% of undocumented migrants entering the European Union arrive via Greece, and because border controls make it hard to continue into the rest of Europe many end up stuck in the country.

According to some estimates, immigrants could now make up as much as 10% of the population.

The Turkish-Greek border is one of the main gateways for immigrants to Europe

This has been an enormous shock for the country which, until recently, was more familiar with outward rather than inward migration. Now, in the grip of a crippling economic crisis and with a welfare system in meltdown, the government lacks the resources to support this new growing population.

Few people are in any doubt that Greece needs an effective programme to manage its undocumented migrants.

Lt Col Christos Manouras of the Hellenic police force says operation Xenios Zeus, launched last August, has slowed down the flow of illegal immigrants. Anyone who looks foreign, or who has aroused suspicion, may be stopped, he says.

"If someone is stopped by the police and they do not have a valid means of identification we will accompany them to the station until their nationality can be determined," he explains.

On patrol in Athens with Xenios Zeus police

"I think that is normal and I would expect Greeks to be subjected to the same treatment abroad."

But while more than 60,000 people have been detained on the streets of Athens since it was launched in August 2012, there have been fewer than 4,200 arrests.

And some visitors to Greece have been detained despite having shown police their passports.

Last summer, a Nigerian-born American, Christian Ukwuorji, visited Greece on a family holiday with his wife and three children.

When police stopped him in central Athens he showed them his US passport, but they handcuffed him anyway and took him to the central police station.

They gave no reason for holding him, but after a few hours in custody Ukwuorji says he was so badly beaten that he passed out. He woke up in hospital.

"I went there to spend my money but they stopped me just because of my colour," he says. "They are racist."

It is impossible to determine how many people have had a similar experience - but enough Americans for the US State Department to issue a warning to its citizens travelling to the country.

It updated its website, external on 15 November to warn of "confirmed reports of US African-American citizens detained by police conducting sweeps for illegal immigrants in Athens", as well as a wider problem in Greek cities of "unprovoked harassment and violent attacks against persons who, because of their complexion, are perceived to be foreign migrants".

Tourism is a major source of revenue in Greece, especially important at a time when many other businesses are going bust. Anything that deterred visitors in large numbers would be a disaster for the economy.

The Greek Foreign Ministry spokesman Grigoris Delavekouras responded to the State Department warning by issuing a statement that "isolated incidents of racist violence which have occurred are foreign to Greeks, our civilization and the long tradition of Greek hospitality."

It is not only tourists who have been affected.

Greek media condemned police for humiliating Rai

In May last year a visiting academic from India, Dr Shailendra Kumar Rai was arrested outside the Athens University of Economics and Business, where he was working as a visiting lecturer.

He had popped out for lunch, and forgotten to take his passport with him.

"The police thought I was Pakistani and since they didn't speak English they couldn't understand me when I tried to explain that I am from India," he says.

When passing students saw their lecturer being held by police and lined up against a wall with a group of immigrants they were horrified and rushed inside to tell his colleagues.

Despite protests from university staff who insisted they could vouch for him, the police handcuffed him and marched him down to the police station.

"Some of my Greek colleagues were almost crying with embarrassment," Rai recalls.

"I understand why the police need to ask for identity documents, they are just doing their job. But I think they are too aggressive - in my country only criminals are handcuffed."

He was eventually released but there was an outcry in the Greek media which asked why an esteemed academic invited to the country to share his knowledge should be humiliated in such a way.

Rai says he experienced no racial prejudice during his time in Greece, and does not accuse the police who arrested him of racism.

But in a report for 2012, external, the Racist Violence Recording Network, a group consisting of 23 NGOs and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, called on the Greek government to "explicitly prevent police officers from racially motivated violent practices" referring to 15 incidents where "illegal acts" had taken place.

There have been a number of reports alleging strong support among the police for Golden Dawn, the ultra-right party that soared in popularity last year, winning 18 seats in June parliamentary elections.

But police spokesman Lt Col Manouras insists that voting preferences are a personal issue.

"Whatever a police officer may feel in their private life, when they come to work and put on the uniform they assume the values of the force," he says.

Greek police have absolute respect for human rights and treat people of all colour and ethnicity as fellow human beings, he says.

"Of course I cannot rule out the possibility that a police officer may have acted improperly," he adds, "but this would be an isolated incident."

Efforts to identify illegal migrants were stepped up last summer

He said he could not comment on the cases of Hyun Young Jung and Christian Ukwuorji, as they are under investigation. The Greek Foreign Ministry did not respond to requests to discuss the cases.

When Jung was released from police custody without charge just a few hours after being detained, he says one officer shouted after him, "Hey Korean, go home!"

Instead Jung went straight to the Korean Embassy in Athens and returned with the consul to confront the men who he said hit him.

It took five further visits to the police station, an official complaint from the embassy to the chief of police and 10 days of waiting before the officers involved in Jung's case were named.

Meanwhile the backpacker had published his story on a travellers' blog, external read by more than 60,000 people.

The case turned into a full-scale diplomatic incident with the Korean ambassador to Greece requesting a meeting with the minister of Public Order, and the Greek Chief of Police, to insist on a fair investigation and just punishment for the officers involved.

Jung, who is now on the last leg of his travels in the US, is still waiting for the police verdict but says that whatever the outcome he will never go back to Greece.

"I travelled through Azerbaijan, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Armenia but I never felt in as much danger as in Athens," he says.

"Whenever people ask me if they should visit Greece I tell them to go to Turkey instead."

Christian Ukwuorji, who also lodged an official complaint against the police with the help of the American Embassy, has now been waiting for more than six months for an outcome.

He would like to see the men who hit him prosecuted, but says he holds out little hope of any justice.

"The police there are very corrupt and nothing will be done about it," he says. "I have learned that this is how Greece is."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external