Lance Armstrong: How it feels to lose faith in your favourite sport

- Published

Bitter, angry, disappointed. As a lifelong cycling fan, that's how I feel after Lance Armstrong's confession. But hopeful too that, maybe, a line can be drawn under the years of lies and deceit.

Imagine how you would feel if you discovered that there had been so much cheating at such a high level across the sport you love, that a decade's worth of results could no longer be relied upon.

What would you think if the sport could no longer say with any great certainty who had won the Premiership, or the World Cup?

That is effectively what has happened in cycling.

And as a dedicated fan, I can tell you that it feels like you have been betrayed. It is as if a good friend that you trusted and shared good times with turned out to be a big fat liar.

It hurts to hear Lance Armstrong, who won the sport's biggest race the Tour de France more times than any other rider, confessing that his seven victories between 1999 and 2005 came with the aid of performance enhancing drugs and blood transfusions.

Taking into account those who cheated before and after him, it means that only one rider who won the Tour de France between 1996 and 2010 is now thought to be clean - Spanish rider Carlos Sastre, who won in 2008.

The US Anti-Doping Agency report on Lance Armstrong, published in October last year, left little room for doubt. He had been a "serial cheat", it said, perpetrating a "massive fraud".

But now we have it in his own words. Ending years of vehement denials, he told Oprah Winfrey that it had all been "one big lie".

This was a man who had helped make cycling a global sport, rather than a primarily continental European one.

And it was during the Armstrong era that I first travelled to France to watch the Tour.

Lance Armstrong admits doping to win cycling titles

Friends were often bemused about why I would bother to make the effort and spend all that time at the roadside only to have a group of men on bikes ride by in a flash.

A bike race is a complex and exciting mix of strategy and strength. It is on the mountain stages where the three-week races are won and lost. As a spectator they are also the most rewarding as you get closest to the riders and can enjoy stunning scenery while you wait.

People pick their spots hours - and even days - before the race is due to arrive, setting out their picnics by the side of the road. In those pre-Twitter days, fans would gather around pocket radios, sharing news of attacks or crashes further down the road, and discussing teams' tactics.

As anyone who goes to watch a match, a game or a race will know, there is a special atmosphere when like-minded people get together for a big event.

A stage of the Tour lasts all day, with the sense of excitement and anticipation building until the sound of helicopters signals the imminent arrival of the noisy, travelling beast that is a professional bike race. Then for an all-too-brief moment, you are part of it, urging the riders on. And it is thrilling.

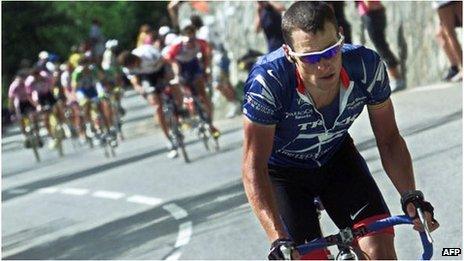

In 2001 I saw Armstrong attack his now also disgraced main challenger, Jan Ullrich, on the slopes of Alpe d'Huez, one of the most famous and toughest climbs in the race.

Armstrong pulling away from Ullrich (in white) moments after "the look"

His successful move, and the way he nonchalantly looked back at former winner Ullrich as he rode away, became one of the Texan's most famous moments, dubbed "the look".

Armstrong's dominance in the long, hot arduous Alpine stages that year, earned him the headline L'Homme de Fer - Iron Man. I still have a framed copy of that front page, although it is no longer on the wall.

When last year's Usada report said his victories in those years were based on "the most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping program the sport has ever seen", I felt like a fool.

I cancelled my Eurosport subscription - just two months after the immense pride I had felt as a cycling fan, when Bradley Wiggins became the first British winner of the Tour.

However, it was not what the Usada report revealed about Armstrong that I found most worrying. A cloud had hung over him and his achievements for years, so when it was finally officially confirmed it was hardly a shock.

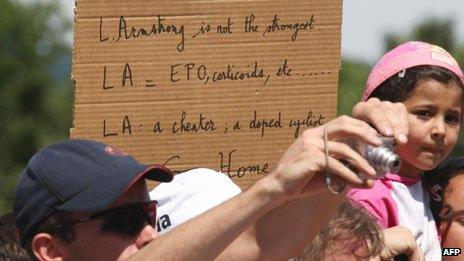

Armstrong told Winfrey he was clean by 2009 - some fans disagreed

What has rocked my faith in the sport I had travelled across Europe to see a dozen times over the years, was the US Anti-Doping Agency's comments on how widespread cheating had been.

The Usada report talked about the "culture of silence" about drug use that had existed not only within Armstrong's team, but across the sport as a whole.

It even called for a Truth and Reconciliation Committee, where cyclists could come forward and admit the extent of their doping. This "may be the only way to truly dismantle the remaining system that allowed this 'EPO and Blood Doping Era' to flourish," the US anti-drugs authority said.

What added to the sense of humiliation was the suggestion that, of course, "everyone knew" that cycling was riddled with cheats.

It was true that individual riders had failed tests and were chucked out with regrettable regularity, but these were isolated cases, surely. Denial? Maybe.

But unless you think that what you are watching is believable, there is no joy in it and you may as well give up. It comes down to a matter of faith and trust.

There is still more to do. And it this is where the regulators come in.

Rabobank, the Dutch company who had sponsored a cycling team for 17 years, pulled out of the sport after the Usada report.

"Enough is enough", it said.

"We are no longer convinced that the international professional world of cycling can make this a clean and fair sport.

"And we are not confident that cycling will improve in the medium term."

Now that Armstrong's confessional session with Oprah Winfrey is over, the focus must shift from what the cyclists did to the regulators, whose job it was to stop it happening, through rigorous testing and controls.

He told Oprah he didn't think it was possible to win the Tour clean and that he didn't fear getting caught. That is not good enough.

There are some reasons for optimism, though.

I believe that the success of Bradley Wiggins and Team Sky in the past year shows that a rider can now win a three-week race clean, or "on bread and water" as the professionals call it.

Also, former dopers such as rider David Millar and Armstrong's former teammate Jonathan Vaughters, who now runs his own professional team, are working to change the culture which led them all to think they had no choice but to cheat to stand a chance.

But only when we know more about the role of the governing body, the International Cycling Union, in the deception that now characterises the Armstrong years, can we have complete faith in the sport.