Should people be off on Fridays?

- Published

- comments

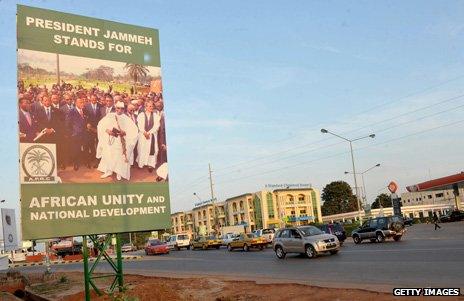

The Gambia has shortened the work week, making Friday a day of rest. Is this the perfect pattern for a working week?

In the tiny African nation of The Gambia, public sector workers will now clock in at 8am and clock out at 6pm, Monday to Thursday. They'll still do a 40-hour week but have the luxury of Friday off.

President Jammeh wants the extra rest day to "allow Gambians to devote more time to prayers, social activities and agriculture".

In the dark days of the 19th Century, many workers in industrialised nations considered themselves lucky if they got Sunday off. The achievement of a 40-hour week with Saturday and Sunday off for many was a major landmark for the labour movement.

But some have tried to go further.

In 2008, about 17,000 government officials in the US state of Utah started working four 10-hour days in a bid to cut costs. The experiment didn't last: the five-day week was reinstated in 2011.

Other US states have also toyed with the idea. Oregon and Texas legislators considered - but did not pass - four-day work week bills, while Georgia and Virginia have trialled it at a handful of agencies.

A four-day week for the good of the country?

The four-day week is also popular in the Netherlands, where one in three men either works part-time or 40 hours in four days. In the UK, certain professions - journalists among them - have often worked a four-day week of longer shifts.

But despite the companies that offer compressed hours, flexible working arrangements or shift work, the nine-to-five, five-day week is still seen as the typical way to earn a living in much of the West.

But what is the ideal working week, and could the four-day week become more widespread?

Steven Shattuck, 28, is a community manager at Slingshot SEO, a search engine optimisation consultancy in Indianapolis, in the US, where everyone works 8am-6pm, Monday to Thursday. He thinks the four-day week is the way forward.

"Everything happens so fast in our industry, we think it's important to have Fridays to recharge. We call them research days. They give people a chance to stay up on things, maybe do some independent research or spend time with their families," he says.

As a result, Shattuck believes time in the office is more productive.

"On Monday mornings people aren't so groggy - they hit the ground running. We have really tight deadlines, it's very collaborative, we try to squeeze as much into our days as possible," he says.

Clients don't see it as a problem, so long as the company - which has 85 employees - delivers, and people are prepared to work in emergencies.

"The four-day week is a real selling point when it comes to recruitment. But we're a young company, the median age is 27 or 28, so I guess it would depend on the company culture," he adds.

There wasn't such a collective approval in Utah, says Winston Inoway, public information officer at the state's Department of Human Resource Management.

"Many employees loved it, but others had issues with childcare, and citizens raised questions over the availability of services on Friday. The projected savings were also higher than the actual savings," he says.

Heating and electrical savings in year one, for example, were projected to be $3m (£1.8m), but the actual saving was $502,000 (£318,669).

An audit also found it hard to find any evidence of increased productivity.

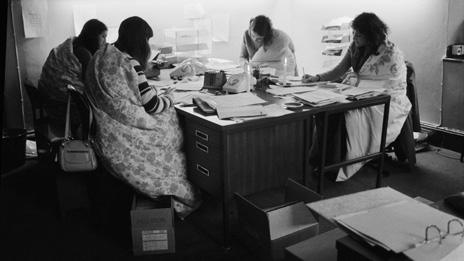

However, proponents of the shorter week cite the three-day week during the recession in 1974, saying production fell by much less than expected. And they say the benefits are not just down to economics.

At work during the power cuts caused by the miners' strike in 1974

There are also environmental and social reasons why work hours should not only be compressed, but substantially reduced, says Anna Coote, head of social policy at the New Economics Foundation.

"If we worked less, there would be more jobs, and that would get people off benefits and reduce unemployment. It would also help people slow down - we are under pressure to live life at such a fast pace.

"We need to live more sustainably, stop buying ready meals because we haven't got time to cook, reduce the carbon footprint by commuting less, and value unpaid things - like being active citizens, caring for people, being better parents," she says.

Coote advocates a 21- to 30-hour working week, which she says would also involve reassessing the minimum wage.

The idea might seem radical, but in 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes envisaged, external we'd be working a 15-hour week by the beginning of the 21st Century, believing that would be enough to suit our material needs.

Instead, "we still have a factory-based model and mindset for the way we work - the more hours we put in the better, which creates a hamster wheel frenzy," says Ian Price, author of Activity Illusion.

"Add technology, and the way it has revolutionised the scale at which we communicate, and there can be a 24/7 working culture."

It is a sentiment shared by Prof Cary Cooper, an expert in organisational psychology and health at Lancaster University Management School.

"It's crazy old-fashioned that people come in at 8am and leave at 7pm on busy commutes, given new technology means they can work from home. Going into the office seems to be part of our DNA, but longer hours are bad for health, and can cause stress," he says.

However, Cooper doesn't think compressed or shortened hours is the answer.

"It's about flexibility - flexible time, flexible place. People want it to happen, it's just a case of convincing managers it's good for them."

The CBI agrees flexibility is the future and says in the UK there is "very much an individual approach taken by employees and businesses towards work and finding an arrangement which benefits both parties".

Its 2011 employment trends survey found 96% of respondents offered at least one form of flexible working, while 70% offered three or more.

However 53% of firms said the nature of work, or the operating hours of the business, was a limiting factor.

John Walker, the national chairman of the Federation of Small Businesses, says most small firms offer flexibility as a matter of course.

But he says a set four-day working week would be "impractical" for businesses like high street convenience stores or plumbers, who are expected to be on hand whatever the day.

"Faced with the need to get the economy into recovery, setting mandatory working days and hours would be far too prescriptive and simply unrealistic for the vast majority of employers," he says.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external