Have young people never had it so bad?

- Published

- comments

Rising wages and low house prices helped the baby boom generation to prosper. Today's young face high unemployment, expensive education, and a lifetime of renting. Have they never had it so bad?

Let's take a typical 24-year-old everyperson. This person lives in Nottingham.

There's a one-bedroom flat they want but it costs £120,000. You need a salary of more than £25,000 to get a mortgage for that.

But this everyperson has no salary. They're one of the 18.5% of people aged 18-24 in the UK who are out of work, external. Our 24-year-old has a degree and a £25,000 debt to pay off from university.

The everyperson has moved back in with their parents, part of the "boomerang adultescents", external.

A job is the most pressing requirement but many of those are now going to older workers. The over-50s accounted for 93% of the job increases over the last decade, according to analysis by investment bank Citi., external

And there's the growing number who put off retiring. Working people of pension age have nearly doubled over the last two decades, reaching 1.4 million in 2011, according to the Office for National Statistics.

In 1957 Harold Macmillan declared: "Most of our people have never had it so good."

Today no politician would utter those words.

Yet there's a growing belief that the generation of baby boomers born in the two decades before 1965 were lucky to live when they did. Houses were easier to come by when young and rocketed in value. Pensions were generous. Unemployment was mostly low. Now, aged between 50 and 70, they have had it pretty good.

The question for today's young might be, have they ever had it so bad?

Baby boomers: From cradle to retirement home

Boom time: A sharp increase in births after World War II created the baby boomer generation, born into an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity.

Roll with it: Babies born between 1948 and 1964 entered an age of such stability that they have subsequently been described by some as self indulgent.

As teenagers in the 60s, baby boomers could look forward to jobs for life and plenty of disposable income. Did this foster an early sense of entitlement?

The 80s saw the last of the baby boomers grow up and go to work. It was the era of Wall Street, the "big bang" in the City and rocketing house prices.

Tony Blair and Bill Clinton: Archetypal baby boomers who grew up to rule their respective nations in the 1990s and 2000s.

Many baby boomers now enjoy a lifestyle that the younger generation can only dream of. They are also working longer and, some say, blocking jobs.

There have been eras indisputably worse. A whole generation went to war in 1914 and 1939. There was the hunger and unemployment of the Great Depression. And child labour in Victorian times.

But take 1963, the year that marked the end of national service and the rise of the Beatles, and you have an interesting cut-off point for comparison. Is 2013 the hardest time for young people in the last 50 years?

Today, for the first time, a person in their 80s has higher living standards than someone working in their 20s, the Financial Times reported in October 2012, external.

Protest against rising fees and youth unemployment

A student who started university in 2011 will graduate with average debts of £26,000 and bleak career prospects.

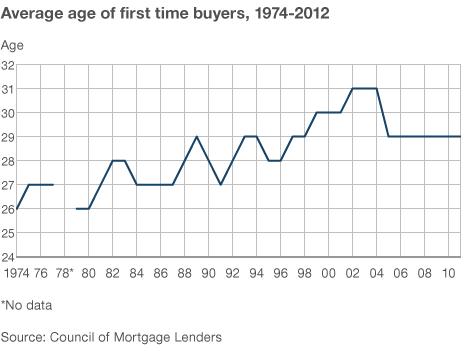

And even the lucky ones who get good jobs face a lifetime of renting, unless the "Bank of Mum and Dad" is willing and liquid enough to help out.

Baby boomers born in the 1940s to mid 60s bought their first home when prices were low and watched property prices shoot up as house-building slowed while the population rose. There was relatively low unemployment up to the 1980s and again in the 1990s and 2000s.

Wages rose. Low inflation and globalisation kept prices down. They got generous pensions.

There was poverty too, but those middle and top earners flourished. They are the lucky generation. So goes the theory.

It's not just young agitators saying this. In 2010, Conservative frontbencher David Willetts, born in the late 1950s, tackled the subject in his book The Pinch. It is subtitled "How the baby boomers took their children's future - and why they should give it back."

Willetts pointed out the crucial role of demography.

When births spiked after the war, it was thought this new generation would struggle due to the competition for jobs and resources.

But the reverse turned out to be true. Being a big generation meant faster economic growth and more lobbying power. "Our slice of the pie might be smaller but the pie will grow faster than in the lifetimes of other cohorts," Willetts explained.

Unemployed young people re-encted the Jarrow Crusade in 2011...

And the baby boomers are living longer, creating an imbalance between workers and retired.

It means our putative 24-year-old faces a future of a small working population supporting a large number of elderly people.

By 2035 it is projected that those aged 65 and over will account for 23% of the total population, external, up from 15% in 1985.

Despite austerity, the state pension has been bolstered, winter fuel payments are outside the reach of means testing, and free bus pass and TV licence retained for the elderly. At the same time the government has cut benefits in real terms and axed the Education Maintenance Allowance in England.

... 75 years after Tyneside's unemployed shipyard workers marched on London

Pensioners have traditionally been portrayed as vulnerable or deserving. But it is time for a rethink, campaigners say.

In October 2011, a new group, the Intergenerational Foundation, argued that older people were "hoarding housing" and should be encouraged to downsize.

"Older generations own more than two-thirds of the nation's housing stock," says Angus Hanton co-founder of the foundation. "They have rewarded themselves with unaffordable pensions and intimidate policy makers through sheer cohort size and lobby-power."

It's dangerous and misleading to talk this way, argues Dot Gibson, general secretary of the National Pensioners Convention. Poverty rates amongst the under-25s and the over-65s both stand at 20%. There are also many shared concerns between young and old such as a lack of suitable housing, she says.

"What this artificial generational conflict fails to recognise is that different generations are already helping out each other inside the family - whereas the real division in our society is between rich and poor."

Gibson alludes to the unofficial redistribution of wealth of parents helping children with their mortgage. But a report for the Resolution Foundation On borrowed time?, external argued that while bequests like this will play a role, many elderly people may consume their wealth rather than passing it on, especially for long-term care.

"Given that it is lower-income pensioners who are most likely to need to draw down their housing equity in this way, we might expect their [often] lower-income families to be less likely to benefit from inheritance," the report predicted.

It comes down to fairness, says James Sefton, professor of economics at Imperial College Business School, who has done economic forecasts at the Treasury. Government debt is stacking up for the young. Meanwhile those born 1945-65 have lived through times of unprecedented plenty.

"If you think about the baby boom generation they lived through peace and unparalleled prosperity. You'd struggle to explain why that generation should be able to leave huge debts to the next generation."

So why are the young not taking to the streets?

They're too busy trying to get by, argues Caroline Mortimer, a recent graduate. "We're aware of the problems of an ageing population. But we can't think about pensions and buying houses because we've got to get an actual job and pay the rent."

She argues that the notion of "respecting your elders" may also have blunted the desire to take on the baby boomers. And there's still an attitude that young people are "ungrateful", she believes. "Older people are worried about their own children but not other people's kids."

And, of course, while the economic situation may look grim, young people do have some advantages over previous generations.

Their world has opened up massively. Expectations are that young people will start work and settle down later. This leaves them free to travel and the costs are much lower than 50 or even 30 years ago.

A return flight to Johannesburg might have cost £500 in 1980, external. By 2008 it was £505, which allowing for inflation was a massive reduction in real terms. A return to Sydney was £716. In 2008 it was £699.

Then there's the field of consumer electronics. In the 1970s and 1980s buying a television was expensive. Having access to entertainment and information was limited.

Computers were exotic and pricey. And that was before you could even go online. "I remember buying my first computer in about 1984," says technology writer Jonathan Margolis. "It was an Amstrad 9512 and cost £400 in Dixons. It was about 6 weeks' wages and considered a huge bargain."

Now you can pick up a laptop for as little as £100. Today nearly all a person's entertainment needs can be found on something that didn't exist 30 years ago - the mobile phone.

But these blandishments may be seen as inadequate compensation for the economic hardships. And baby boomers get the same gadgets and cheap travel.

The generational squeeze hasn't hit home yet, says Sefton. But it's coming. The solution may be for the better off in that generation taking over responsibility for their own health and social care, he argues. Rich countries - Norway, South Korea, Singapore - have set up investment funds to provide for future generations.

You could argue this is just boom and bust writ large. The economy grows, baby booms happen. You can't penalise a generation that was lucky. Willetts, who is now the Universities Minister, disagrees. Demography makes it too big a gap.

"When you look at the hard financial facts of the houses we own and the pensions we've built up, it's a big challenge to the baby boomer generation to which I belong."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external