The difficulty of dealing with groping

- Published

Office groping is back in the headlines. But it's a difficult subject to talk about and even define.

A hand on a colleague's shoulder, perhaps a squeeze of the arm, a pat on the head.

A brush of the hand over the waist. A pat on the bottom.

There's a spectrum here, most people would probably admit.

At one end you have physical contact that could be construed as a sympathetic gesture.

But repeat the gesture over the course of dozens of working days, in particular contexts, and it's something that could easily be seen as a creepy invasion of personal space.

Deliberately touching a colleague's bottom carries no such ambiguity though. In a British or American workplace it's likely to trigger an investigation and could lead to dismissal.

How victims should respond to groping, how organisations should investigate allegations and even what constitutes groping is all open to debate.

Groping is something serious and overtly sexual whereas there is a wider, and less serious sounding, category dubbed "inappropriate contact" or even just "inappropriate behaviour".

The semantics are important as they help define the debate, external.

There can be serious non-physical sexual harassment. And for many people, there is innocent touching that cannot be construed as sexual harassment.

To further complicate, there is touching that is sexual harassment but in the eyes of some still does not deserve to be termed "groping".

Addressing the issue can be intensely complicated.

The allegations against Lord Rennard have prompted the Lib Dems to launch two inquiries. The Metropolitan Police is investigating whether criminal acts took place. Lord Rennard, who stepped down as chief executive of the party in 2009, has said the claims are a "total distortion" of his character.

Offices in the 1960s and 1970s had a different climate

In October, the BBC appointed Dinah Rose QC to help with a review of how it handled sexual harassment.

The Rennard case has again prompted a flurry of debate.

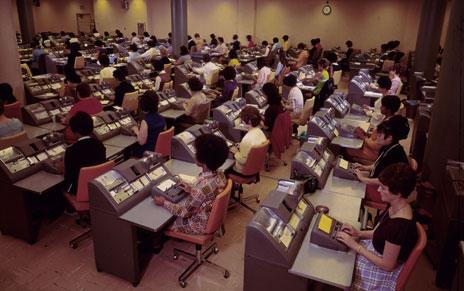

Once upon a time, fending off groping was almost part of the job for women. Mad Men-style sexism was de rigueur in 1960s offices, says the Independent newspaper's agony aunt Virginia Ironside.

"You were groped uphill and down dale and nobody cared. They'd be twanging your suspender belt as you leant over the waste paper basket."

Things are supposed to have changed. Today the "cheeky" pat on the bottom is considered harassment. Firms have zero tolerance bullying strategies and policies to encourage whistleblowers.

It's hard to measure the scale of the problem. There's a dearth of reliable stats, prompted at least in part by chronic underreporting.

Scarlet Harris, women's equality officer at the Trades Union Congress, says groping is still a "massive problem". It's likely to be underreported as many women decide to "deal with it" rather than report it, she says. "It's a terrible state of affairs if a woman feels she has to ignore it."

And it's a problem that affects many men, external of course, inappropriately touched by both women and men. The typical case is perceived as being a woman being touched by a man, but increasing numbers of female managers have created plenty of evidence of the reverse.

In all cases, if it's a more senior person doing the touching, the dynamic changes.

The Everyday Sexism Project, external launched in April 2012 has collected 20,000 women's stories, of which about 4,000 occurred in the workplace.

One reads: "An arm round my shoulders with the hand resting on my breast or almost cupping my breast (on multiple occasions). I had a senior manager who frequently used to try and do this to all the female staff necessitating a side-step movement to get away. A complaint was made but nothing changed."

Another woman wrote: "I had a boss whose trick was to stand behind seated women staff and rest his groin on their shoulder."

Matthew Gwyther, editor of Management Today, says firms would be stupid to ignore even rumours of groping.

"If you're hearing that you've got a groper on your staff, you would be mad not to take some kind of action."

These days simply talking to someone "man to man" is not acceptable.

Most human resources departments will have procedures to follow in the case of sexual harassment. Fairness must be scrupulously observed for both the alleged victim and perpetrator, says Dianah Worman, diversity adviser at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

The facts have to be established. Both parties should be talked to. In the case of rumours, a manager should report the case to HR to investigate. It needs to be handled sensitively in order to avoid someone having their character tarnished unfairly, she cautions.

The individual may not realise their behaviour is unacceptable. "The intention doesn't matter though it's the way that someone perceives being touched," says Worman.

Somebody could be doing something they regard as innocuous. The recipient could have a very different view. Third parties could be split down the middle as their judgement is subjective - how would they have felt in the same situation?

Objective standards are hard to come by.

A squeeze of the shoulder might be innocent. But any form of touching between colleagues can, in theory, trigger an assault charge, says Andrew Lilley, employment law partner at Travers Smith.

Workplace cases are normally settled through civil law. An employment tribunal is often quicker and less daunting for victims than involving the police, Lilley says.

The context will be important. But motive - for example to say it was a friendly gesture - is not necessarily a defence.

The only way to ever be sure is not to touch other employees, Lilley says. Gwyther agrees. "Touching someone can be done with the best of intentions. But you've got to be incredibly careful."

Ironside feels the debate has become unbalanced. "Endless fondling and horrible remarks are obviously ghastly." But the pat on the bottom or hand on the knee that would happen in offices was usually banter rather than something sexual, she argues.

"It's not harmful or violent. It's frankly irritating."

For colleagues to avoid touching each other would be sad though, she argues. "Sometimes you want a touch or someone to press your hand if you're feeling low. Zero touching is a very creepy development."

Harris disagrees.

"As a rule of thumb, don't touch anyone at all is a good one to work by."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published13 January 2012