The man who demolished Shakespeare's house

- Published

Britain hasn't always been in love with its heritage. It took some shocking acts of destruction, and some very near misses, to help shape the way it is now treasured and protected.

The UK today has some of the most powerful conservation laws in the world.

This year marks 100 years since the first legislation was passed giving the government power to act directly when a historic site was under threat.

The country's heritage is now treasured and has become big business, but it wasn't always the case. In the 19th Century most historic sites were in private hands and owners could do whatever they liked with them, including raze them to the ground.

But a small group of pioneers knew heritage was something to treasure and by saving it shaped the Britain we know today. They were driven by some acts of destruction, and some very near misses, that are shocking today.

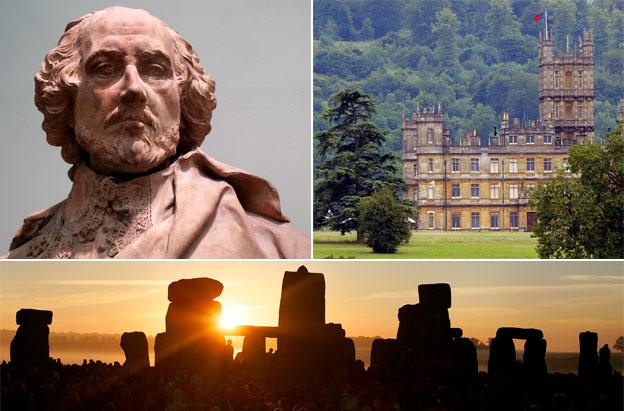

The man who demolished Shakespeare's house

New Place, Stratford-upon-Avon. William Shakespeare's final home.

It's where he is believed to have written some of his later works, such as The Tempest, and where he died in 1616, according to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. A building of huge cultural and historical importance - the very definition of a national treasure.

Not an opinion shared by the Reverend Francis Gastrell. He bought the house in 1753 but quickly got irritated with tourists wanting to see it, says architectural historian Gavin Stamp. He is also said to have been in a dispute over taxes with local officials.

Gastrell was already in the town's bad books after chopping down a mulberry tree planted by Shakespeare in the garden. Then, in an extraordinary fit of spite, he demolished the whole house in 1759. It was never rebuilt and only the foundations remain.

The people of Stratford-upon-Avon were horrified and Gastrell became so unpopular he eventually had to move out of the town, says Stamp. He wasn't the only property owner to begrudge tourists.

"In 1808 Lady Howe knocked down Alexander Pope's villa in Twickenham for the same reason," says Stamp. "This was much to the disgust of the painter Turner, who lived nearby.

"There are shocking examples in history of buildings being demolished by their owners just because other people were interested in them or they were of national importance.

"Owners like Gastrell could do whatever they liked, the government had no powers to stop them. They believed they had the absolute right to destroy their properties."

The idea that the state could stop someone doing whatever they wanted to their own property was ridiculous at the time. That Britain's heritage was worth preserving was a belief held by just a few radicals, say historians. But after witnessing decades of such destruction they became determined to do something.

Action taken by one, John Lubbock, the Liberal MP for Maidstone in Kent, led to the first piece of legislation to safeguard Britain's heritage - the Ancient Monuments Bill.

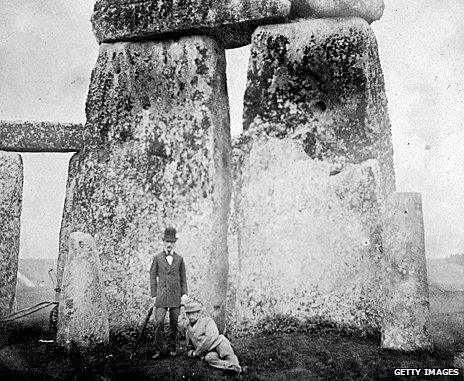

The picnickers who nearly toppled Stonehenge

Even when there was interest in ancient sites it wasn't necessarily to do with preserving them. By the late 1800s more and more people were visiting Stonehenge for a day out. Now a World Heritage Site owned by the Crown, at the time it was privately owned and neglected.

But the picnickers left behind litter and leftover food. It encouraged rats and rabbits that burrowed away at the stones' foundations, weakening them, say historians.

One of the upright stones had already fallen over and a lintel had broken in two. They also chipped pieces off the stones for souvenirs and carved graffiti into them, says architectural critic Jonathan Glancey.

It was the same for other pre-historic remains, which were disappearing fast. Threats also included farmers and landowners as the ancient stones got in the way of ploughing and were a free source of building materials.

Outraged, Lubbock took up the fight. When he heard Britain's largest ancient stone circle at Avebury in Wiltshire was up for sale in 1871 he persuaded its owners to sell it to him and the stone circle was saved. This year it was named the second best heritage site in the world for visitors by Which? Travel magazine.

"Lubbock aroused national attention [for] ancient monuments," says Glancey. "At the time places like Stonehenge were just seen as a collection of stones, ancient quarries to get building materials.

"Lubbock knew they were the roots of British identity. He did for heritage what Darwin did for natural history."

But Lubbock couldn't buy every threatened site. He knew laws were needed and tabled the Ancient Monuments Bill. It proposed government powers to confiscate any pre-historic site under threat from uncaring owners, a radical idea at the time.

For eight years he tried and failed to get the bill through parliament. Finally, in 1882, it was voted into law. It had, however, been watered down, people had to voluntarily give their ancient monuments to the government. But what it did do was plant the idea that the state could preserve Britain's heritage better than private owners.

Pressure started to be put on the owners of sites like Stonehenge to take better care of them.

A mania for excessive makeovers

It was the Victorian fashion for romantic interiors that posed another threat to Britain's heritage.

Artefacts and curiosities from ancient sites across Britain and around the world were in demand when it came to wealthy Victorians, say historians.

"The idea that historic things should remain in the place from where they came was still not the view taken by a lot of people," says Anna Keay, from the Landmark Trust.

Another problem was that work done on old buildings was often overzealous, unsympathetic and kitsch.

"Often the building was ripped apart and made to look as new as possible," says Glancey.

Angry about amateurish makeovers, Arts and Crafts visionary William Morris set up the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877. It was Britain's first effective pressure group dedicated to saving old buildings.

It sent members across the country to identify sites and buildings at risk. It also held public meetings to protest against bad restorations and support the preservation of old buildings in their original state.

The painter John Ruskin also took up the fight, concerned the British landscape was threatened by industrialisation. He set up the Guild of St George in 1870s to protect the Lake District.

The case of the missing fireplaces

It wasn't only the British who went trophy hunting. The speed of change at the turn of the 20th Century resulted in opportunities that made some people very rich, very quickly, and none more so than in America.

With cash to splash, these self-made millionaires went shopping and they came to Britain to do it. Ancient structures and architectural features were dismantled and shipped across the Atlantic.

It was the plight of the rare medieval castle of Tattershall in Lincolnshire that spurred one man to act. Lord Curzon of Kedleston had already successfully fought to save much of India's heritage while he was Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905, including the Taj Mahal. He was about to do the same for Britain.

Neglected for years, Tattershall was put up for sale in 1910. Its greatest treasures were still intact - huge medieval fireplaces. When an American bought them they were ripped out and packaged up for shipping.

Curzon stepped in at the eleventh hour to buy the castle and was determined to get the fireplaces back. After a nationwide hunt they were found in London and returned. Curzon went on to completely restore the tower and left it to the National Trust when he died in 1925.

The experience spurred him to push for protection laws. In 1913 he got the Ancient Monuments and Amendments Act passed, which for the first time gave the government powers to act directly when a historic site was under threat. Landowners could be forced to repair structures or be fined and unpaid fines could lead to imprisonment.

"Curzon's Bill reintroduced the idea of compulsion, the idea that was originally in Lubbock's act and had be taken out because it was considered intolerable," says Simon Thurley, chief executive of English Heritage.

The legislation excluded anything built after the medieval age and any inhabited buildings, but the freedom to do what you liked as a landowner was now over.

It was a landmark in the fight to save Britain's heritage.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external