When are we going to learn to trust robots?

- Published

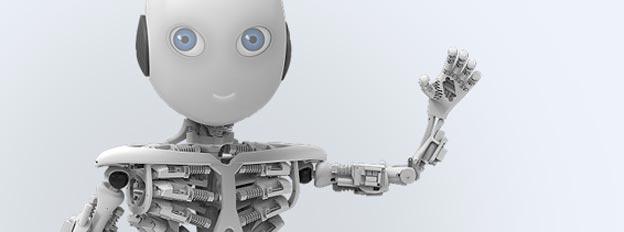

A new robot unveiled this week highlights the psychological and technical challenges of designing a humanoid that people actually want to have around.

Like all little boys, Roboy likes to show off.

He can say a few words. He can shake hands and wave. He is learning to ride a tricycle. And - every parent's pride and joy - he has a functioning musculoskeletal anatomy.

But when Roboy is unveiled this Saturday at the Robots on Tour event in Zurich, he will be hoping to charm the crowd as well as wow them with his skills.

"One of the goals is for Roboy to be a messenger of a new generation of robots that will interact with humans in a friendly way," says Rolf Pfeifer from the University of Zurich - Roboy's parent-in-chief.

As manufacturers get ready to market robots for the home it has become essential for them to overcome the public's suspicion of them, external. But designing a robot that is fun to be with - as well as useful and safe - is quite difficult.

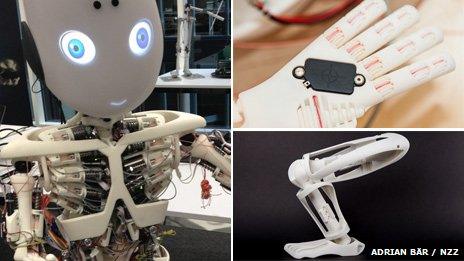

Roboy's main technical innovation is a tendon-driven design that mimics the human muscular system. Instead of whirring motors in the joints like most robots, he has around 70 imitation muscles, each containing motors that wind interconnecting tendons. Consequently, his movements will be much smoother and less robotic.

But although the technical team was inspired by human beings, it chose not to create a robot that actually looked like one. Instead of a skin-like covering, Roboy has a shiny white casing that proudly reveals his electronic innards.

Behind this design is a long-standing hypothesis about how people feel in the presence of robots.

In 1970, the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori speculated , externalthat the more lifelike robots become, the more human beings feel familiarity and empathy with them - but that a robot too similar to a human provokes feelings of revulsion.

Mori called this sudden dip in human beings' comfort levels the "uncanny valley".

"There are quite a number of studies that suggest that as long as people can clearly see that the robot is a machine, even if they project their feelings into it, then they feel comfortable," says Pfeifer.

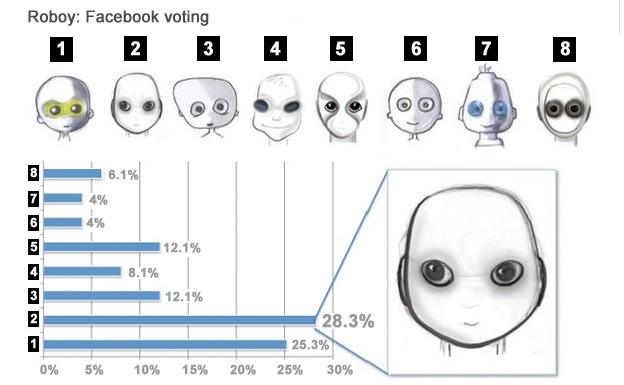

Roboy was styled as a boy - albeit quite a brawny one - to lower his perceived threat levels to humans. His winsome smile - on a face picked by Facebook users from a selection - hasn't hurt the team in their search for corporate sponsorship, either.

But the image problem of robots is not just about the way they look. An EU-wide survey, external last year found that although most Europeans have a positive view of robots, they feel they should know their place.

Eighty-eight per cent of respondents agreed with the statement that robots are "necessary as they can do jobs that are too hard or dangerous for people", such as space exploration, warfare and manufacturing. But 60% thought that robots had no place in the care of children, elderly people and those with disabilities.

The computer scientist and psychologist Noel Sharkey has, however, found 14 companies in Japan and South Korea that are in the process of developing childcare robots.

South Korea has already tried out robot prison guards, and three years ago launched a plan to deploy more than 8,000 English-language teachers, external in kindergartens.

Cute, toy-like robots are already available for the home.

Take the Hello Kitty robot, which has been on the market for several years and is still available for around $3,000 (£2,000). Although it can't walk, it can move its head and arms. It also has facial recognition software that allows it to call children by name and engage them in rudimentary conversation.

A tongue-in-cheek customer review of the catbot on Amazon reveals a certain amount of scepticism.

"Hello Kitty Robo me was babysit," reads the review.

"Love me hello kitty robo, thank robo for make me talk good... Use lots battery though, also only for rich baby, not for no money people."

The product description says the robot is "a perfect companion for times when your child needs a little extra comfort and friendship" and "will keep your child happily occupied". In other words, it's something to turn on to divert your infant for a few moments, but it is not intended as a replacement child-minder.

An ethical survey, external of "robot nannies" by Noel and Amanda Sharkey suggests that as robots become more sophisticated parents may be increasingly tempted to hand them too much responsibility.

The survey also raises the question of what long-term effects will result from children forming an emotional bond with a lump of plastic. They cite one case study in which a 10-year-old girl, who had been given a robot doll for several weeks, reported that "now that she's played with me a lot more, she really knows me".

Noel Sharkey says that he loves the idea of children playing with robots but has serious concerns about them being brought up by them. "[Imagine] the kind of attachment disorders they would develop," he says.

But despite their limitations, humanoid robots might yet prove invaluable in narrow, fixed roles in hospitals, schools and homes.

"Something really interesting happens between some kids with autism and robots that doesn't happen between those children and other humans," says Maja J Mataric, a roboticist at the University of Southern California. She's found that such children respond positively to humanoids and she is trying to work out how they can be used therapeutically.

In their study, the Sharkeys make the observation that robots have one advantage over adult humans. They can have physical contact with children - something now frowned upon or forbidden in schools.

"These restrictions would not apply to a robot," they write, "because it could not be accused of having sexual intent and so there are no particular ethical concerns. The only concern would be the child's safety - for example, not being crushed by a hugging robot."

When it comes to robots, there is such a thing as too much love.

"If you were having a mechanical assistant in the home that was powerful enough to be useful, it would necessarily be powerful enough to be dangerous," says Peter Robinson of Cambridge University. "Therefore it'd better have really good understanding and communication."

His team are developing robots with sophisticated facial recognition. These machines won't just be able to tell Bill from Brenda but they will be able to infer from his expression whether Bill is feeling confused, tired, playful or in physical agony.

Roboy's muscles and tendons may actually make him a safer robot to have around. His limbs have more elasticity than a conventional robot's, allowing for movement even when he has a power failure.

Rolf Pfeifer has a favourite question which he puts to those sceptical about using robots in caring situations.

"If you couldn't walk upstairs any more, would you want a person to carry you or would you want to take the elevator?"

Most people opt for the elevator, which is - if you think about it - a kind of robot.

Pfeifer believes robots will enter our homes. What is not yet clear is whether the future lies in humanoid servants with a wide range of limited skills or in intelligent, responsive appliances designed to do specific tasks, he says.

"I think the market will ultimately determine what kind of robot we're going to have."

You can listen to Click on the BBC World Service. Listen back to the robots for humans special via iplayer or browse the Click podcast archive.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external.

- Published16 March 2012