Why are the French drinking less wine?

- Published

Does the seemingly perpetual decline in consumption of France's national drink symbolise a corresponding decline in French civilisation?

The question worries a lot of people - oenophiles, cultural commentators, flag-wavers for French exceptionalism - all of whom have watched with consternation the gradual disappearance of wine from the national dinner table.

Recent figures merely confirm what has been observed for years, that the number of regular drinkers of wine in France is in freefall.

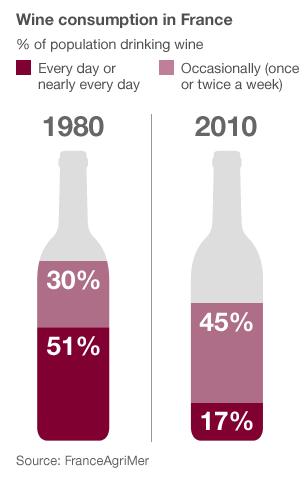

In 1980 more than half of adults were consuming wine on a near-daily basis. Today that figure has fallen to 17%.

Meanwhile, the proportion of French people who never drink wine at all has doubled to 38%.

In 1965, the amount of wine consumed per head of population was 160 litres a year. In 2010 that had fallen to 57 litres, and will most likely dip to no more than 30 litres in the years ahead.

At dinner, wine is the third most popular drink after tap and bottled water. Sodas and fruit juices are catching up fast and are now just a short way behind.

According to a recent study in the International Journal of Entrepreneurship, changes in French drinking habits are clearly visible through the attitudes of successive generations.

People in their 60s and 70s grew up with wine on the table at every meal. For them, wine remains an essential part of their patrimoine, or cultural heritage.

The middle generation - now in their 40s and 50s - sees wine as a more occasional indulgence. They compensate for declining consumption by spending more money. They like to think they drink less but better.

Members of the third generation - the internet generation - do not even start taking an interest in wine until their mid-to-late 20s. For them, wine is a product like any other, and they need persuading that it is worth their money.

"What has happened is a progressive erosion of wine's identity, and of its sacred and imaginary representations," say the report's authors, Thierry Lorey and Pascal Poutet.

"Over three generations, this has led to the changes in France's habits of consumption and the steep declines in the volume of wine that is drunk."

The fall in consumption is mirrored in other countries - such as Italy and Spain - which are also historic producers of wine. And it has not dented the prospects for exports of French wine, which continues to hold its own abroad.

But what worries people are the effects of the change on life inside France, on French civilisation.

They fear that time-honoured French values - conviviality, tradition and appreciation of the good things in life - are on the way out. Taking their place is a utilitarian, "hygieno-moralistic" new order, cynically purveyed by an alliance of politics, media and global business.

"Wine is not some trophy product that we roll out to celebrate the grand occasions or to show off our social status. It is a table drink intended to accompany the meal and provide a complement to whatever is on our plate," says food writer Perico Legasse.

"Wine is an element in the meal. But what has happened is that it's gone from being popular to elitist. It is totally ridiculous. It should be perfectly possible to drink moderately of good quality wine on a daily basis."

For Legasse, part of the fault is a changing national approach to food and gastronomy as a whole.

"For many years people have been steadily abandoning what in our French sociology we referred to as the repas, or meal, by which I mean a convivial gathering around a table, and not the individualised, accelerated version we see today.

"The traditional family meal is withering away. Instead we have a purely technical form of nourishment, whose aim is to make sure we fuel up as effectively and as quickly as possible."

Wine drinking in France is certainly part of a long-standing way of life, but it would be wrong to suppose that the French have always drunk as much as they did, say, 50 years ago.

In the Middle Ages, wine was commonly drunk (at least in wine-growing areas), but it was a weak concoction and popular mainly because - unlike water - it was safe.

The Revolution of 1789 dispelled the aristocratic image that wine had, by then, acquired, and the economic changes of 19th Century helped it permeate society.

French soldiers in WWI drank wine for its fortifying qualities

Denis Saverot, editor of La Revue des Vins de France magazine, says the rise of wine mirrored the rise of the working class. But it was the war of 1914-18 that really secured its position in the hearts of the French.

"Basically the soldiers went over the top pickled on pinard, the strong, low-quality wine which was supplied in bulk. Up until then the Normans, the Bretons, the people of Picardy and the north, they had never touched wine. But they learned in the trenches.

"After that in France we generalised the consumption of cheap wine so that by the 1950s there were drinking outlets, cafes and bars, everywhere. Tiny villages would have five or six. But that was the high point. The decline in consumption goes back to the 1960s."

Everyone agrees on the main factors. Fewer people work outdoors, so the fortifying qualities of wine are less in demand. Offices require people to stay awake, so lunchtimes are, by and large, dry.

Then there is the rise of the car ("wine's worst enemy" for Saverot), changing demographics, with France's large Muslim minority, and the growing popularity of beers and mixers.

But Saverot has another target in his sights.

"It is our bourgeois, technocratic elite with their campaigns against drink-driving and alcoholism, lumping wine in with every other type of alcohol, even though it should be regarded as totally different," he says.

"Recently I heard one senior health official saying that wine causes cancer 'from the very first glass'. That coming from a Frenchman. I was flabbergasted. In hock with the health lobby and the politically correct, our elites prefer to keep the country on chemical anti-depressants and wean us off wine.

"Just look at the figures. In the 1960s, we were drinking 160 litres each a year and weren't taking any pills. Today we consume 80 million packets of anti-depressants, and wine sales are collapsing. Wine is the subtlest, most civilised, most noble of anti-depressants. But look at our villages. The village bar has gone, replaced by a pharmacy."

Veteran observer of his nation's way of life, Oxford-based French writer Theodore Zeldin agrees that a business-style culture has made huge inroads into France - the bane of all those who prefer to take the time to savour things.

"Companionship has been replaced by networking. Business means busy-ness, and in that way we are becoming like everywhere else," he says.

US politicians choose diners for photo opportunities, the French go for wine

But Zeldin refuses to abandon hope.

"The old French art de vivre is still there. It's an ideal. It's a bit like the ideal of an English gentleman. You don't often find an English gentleman, but the ideal is there and it informs society as a whole," he says.

"It is the same with our art de vivre. Of course times have changed, but it still survives. It is that feeling you get in France that in human relations we need to do more than just conduct business. We have a duty to entertain, to converse. And in France - thanks to our education system - we still have that ability to converse in a general, universalist way that has been lost elsewhere.

"That is the art de vivre. It is about taking your time. And wine is part of it, because with wine you have to take your time.

"After all, that is one of the great things about wine. You can't swig it."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external