The trouble with using police informants in the US

- Published

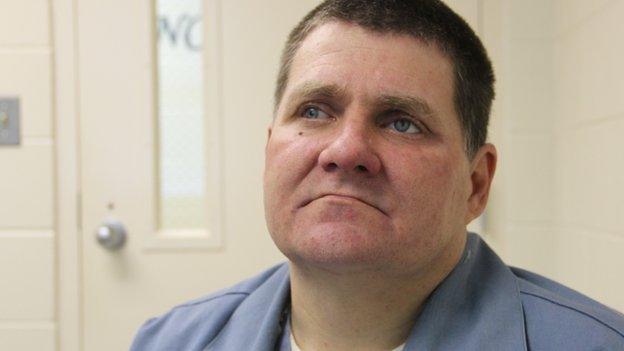

John Horner was asked to become an informant

Some law enforcement agencies in the US use informants in as many as 90% of their drug cases. But there are surprisingly few rules on how informants are used and a groundswell of calls for the system to be reformed.

"Snitches" are staple fare in Hollywood crime dramas, often working secretly with the police to bring down mafia godfathers or powerful drug cartels.

The reality of informants in the US criminal justice system is usually rather different.

Take the case of 46-year-old John Horner, a fast-food restaurant worker who was prescribed painkillers after he lost an eye in an accident in 2000.

Three years ago he was befriended by a man called Matt (not his real name).

"We kind of clicked right off the bat. One day he came to where I worked. We were standing there talking, and I realised he was in pain," says Horner.

"He laid it out on me, 'Look dude, I can either pay my rent or go buy my prescriptions. I can't do both.' I decided Matt was a friend. I said, 'I'll help you out.'"

What Horner didn't know was that Matt was an informant working for the Osceola County Sheriff's Office in central Florida.

Over a period of several weeks, Horner provided Matt with four bottles of prescription pain pills - morphine and hydrocodone. He says he also lent him money. On the last occasion Horner handed over pills, he was arrested.

"The next thing I know I got a guy's knee in the back of my neck grinding my face into the concrete. I'm told, 'You're under arrest for trafficking.'"

According to Sheriff's Office documents, Matt paid Horner a total of $1,800 (£1,200) for the pills, in three separate payments. The money had been provided by agents who also recorded the transactions.

Horner maintains he only received part of that money from Matt, and he believed it was a repayment of cash he'd lent him earlier.

Whatever the case, under Florida law Horner now faced a minimum sentence of 25 years, if found guilty.

"My public defender told me, 'They got you dead to rights.' So I thought, 'OK, I guess there's no need taking this to trial.'"

Prosecutors offered a plea bargain of 15 years if Horner accepted a guilty plea.

"I said, 'My youngest daughter will be 25 years old when I get out. I can't do that.'"

That left him with only one option - to become an informant himself.

Under the deal he signed with prosecutors, he agreed to plead guilty. But if he helped make prosecutable cases against five other people on drug-trafficking charges - charges carrying 25-year minimum terms - his own sentence could be reduced from 25 years to 10.

That choice - put crudely, do the time or snitch - is one faced by thousands of Americans every year.

"The use of criminal informants is often very helpful in penetrating organised crime, but that's not how we use criminal informants in this country - we use them everywhere," says Alexandra Natapoff, professor of law at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

"Every case is open to negotiation."

The number of informants has exploded in the past few decades. The main reason is the tough mandatory minimum sentences introduced in the 1980s for even relatively minor drug crimes.

Snitching offers one of the few escape hatches.

"Every defendant facing a mandatory minimum sentence will be confronted with the reality that becoming an informant may be the only way to get out from under those very high sentences," says Natapoff.

But Florida is one state where the snitching system has attracted criticism - and where attempts to reform it have begun.

These were largely sparked by the case of Rachel Hoffman, a 23-year-old college graduate.

In 2008, she was caught with marijuana and ecstasy in her apartment. To escape charges that could have resulted in a five-year prison term, she agreed to become an undercover informant for the Tallahassee Police Department.

The police sent her out on a sting operation with $13,000 (£8,600) in cash to buy cocaine, ecstasy and a gun from two convicted criminals.

But despite the presence of 19 undercover officers, and a surveillance plane circling overhead, police lost track of her.

"She never had any police training, they never did a dry run of this, there was no tracking device in her car," says her father, Irv Hoffman, a mental health counsellor.

Rachel Hoffman was murdered with the gun the police had sent her to buy when the suspects found a police recording device in her purse.

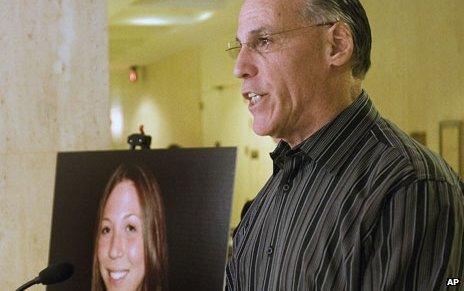

Irv Hoffman at his daughter Rachel's grave

Subsequent investigations were damning, listing a whole series of police failings and incompetence.

But the botched sting operation opened a debate in Florida about the ways confidential informants were being used.

"I got contacted by people from all over the state saying their kid had been put in a dangerous situation over a couple of marijuana cigarettes. They felt that confidential informants had no rights and that they were expendable," says Hoffman.

According to Natapoff, the lack of effective regulation on police use of informants is a nationwide problem.

"There are almost no rules constraining the government in its effort to persuade people to co-operate, the threats they can make to induce people to become informants, and how they are handled after that," she argues.

But many in Florida's law enforcement community are keen to stress the crucial role that informants play.

"An agent can't go up to an organisation and introduce himself and try and get in the door to be able to make a case to prosecute a trafficking organisation. It takes confidential informants to get you through that door," says Larry Zweig, director of Orlando's Metropolitan Bureau of Investigation, which targets drug trafficking and organised crime in central Florida.

He estimates that his officers use confidential informants in 90% of drug cases.

"They made that life-changing decision to become part of the illegal drug trade and now that they've been charged and arrested and are looking at a conviction, this is an option that they have," he says.

Horner says the problem for him, as someone with no previous drug arrests, was finding drug dealers to inform on.

"You start running the streets. You go to the places where drug dealers go, trying to find drugs.

"I had gotten to the point at the end, I was desperate, I didn't care who went to jail. I would have taken anybody down, just so I could be with my family," says Horner.

Irv Hoffman is lobbying for stricter laws around the use of informants

Natapoff says this is the danger the informant system poses.

"We've created thousands of little criminal entrepreneurs running around looking for other people to snitch on," she says.

"And when they don't have information we've created a massive incentive for them to create it."

Horner failed to make cases against drug traffickers.

As a result, he was sentenced to the full 25 years in October last year and is now serving his sentence in Liberty Correctional Institution, outside Tallahassee. He will be 72 by the time he is released.

Osceola County Sheriff's Office did not respond to requests for comment on Horner's case, including his assertion that Matt unfairly set him up by befriending and borrowing money from him, in the process of trying to buy drugs.

The state attorney's office, which prosecuted Horner, told me that Florida law provides defendants with extensive access to evidence to help them decide whether to plead guilty or seek a trial, and that Horner had the benefit of a lawyer when he made the decision to plead guilty.

Since 2009, Florida has introduced more rules on the use of informants than exist in many US states.

That year, following lobbying from Rachel Hoffman's parents, the state legislature passed "Rachel's Law", which set out for the first time some minimum standards police have to meet when recruiting informants and assessing the risks they may face.

But Rachel's father, Irv, says it's not enough. He's calling for a new law to provide greater protection for minors and those in drug treatment programmes.

"People don't know their rights, they're coerced, bullied into doing things that are wrong, and we want people to know that they have rights," he says.

There are also now some signs of a nationwide reform movement.

"We're seeing around the country legislators grappling with this question: 'How should we permit the government to cut these deals with criminal offenders?'" says Natapoff.

But Horner believes the first priority should be reforming the laws on mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes.

"You bust the little man, the little man snitches on the bigger man, he faces 25 years, so he turns round and snitches on a bigger man. That's the way this law was written, for the drug cartel and the mafia," he says.

"It was written so you could go up the chain of command. But that's not what it's doing. It's all the little guys at street level that are fighting each other."

The irony is that if Horner been an experienced drug dealer, he may well now be serving a much shorter term than 25 years.

"What snitching does is it rewards the informed, so the lower you are on the totem pole of criminal activity, the less useful you are to the government," says Natapoff. "The higher up in the hierarchy you are, the more you have to offer."

Court records show that Matt, the person who informed on Horner, had a lengthy record of drug offences. At the point he informed on Horner, he was facing a minimum sentence of 15 years for trafficking. He was ultimately sentenced to just 18 months and is now free.

Rob Walker's documentary Snitching in the USA is broadcast on the BBC World Service at 09:05 GMT on 28 March. Listen back via BBC iPlayer Radio, or browse the podcast documentary archive.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external.