LucasArts nostalgia: Remembering The Secret of Monkey Island

- Published

The demise of LucasArts will make many fans over the age of 30 fondly reminisce about The Secret of Monkey Island. Here, one point-and-clicker remembers.

"My name's Guybrush Threepwood and I want to be a pirate."

"You want to be a pirate eh? You look more like a flooring inspector."

The Secret of Monkey Island wasn't a first-person shooter.

In 1990, it defined the genre of the point-and-click adventure game. It revolved around unthreatening youngster Guybrush Threepwood in his quest to be a pirate.

But this straightforward plot was accompanied by a slew of film references, many relating to Lucasfilm's Raiders of the Lost Ark, a generally cinematic sweep and a genuine effort to put humour at the centre of a game.

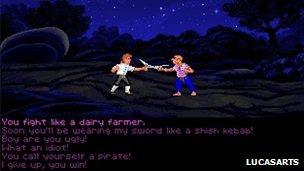

Monkey Island and its lauded sequel conjured up a world where swordfights could be won with insults and puzzles solved with silliness-infused abstract thinking.

There are not many computer games that still seem to matter after more than two decades.

But Threepwood's not-so-swashbuckling pirate did influence the way games were made. It still stands as a touchstone for the point-and-click adventure game genre.

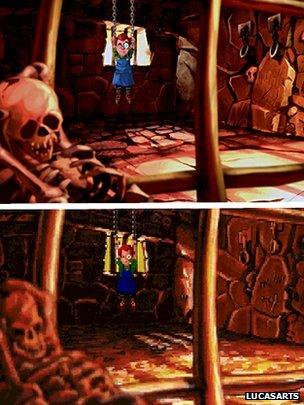

The graphics were updated for the 2009 re-release

Today, in an industry now dominated by action games, an adventure which tells a story through solving puzzles, pointing and clicking and looking over every inch of the screen before moving on would be a harder sell.

Games produced by LucasArts before its closure had moved away from adventure and moved nearly exclusively towards the Star Wars franchise.

In the statement announcing its closure, its reliance on a single franchise was clear.

"After evaluating our position in the games market, we've decided to shift LucasArts from an internal development to a licensing model, minimising the company's risk while achieving a broader portfolio of quality Star Wars games," it read.

There is a certain irony in the fact that the creator of Monkey Island had the idea while on the Pirates of the Caribbean ride at Disney World.

"When Monkey Island came out, it didn't do very well," says Ron Gilbert, Monkey Island co-creator and former LucasArts employee.

"It wasn't a huge seller, it didn't get incredibly good reviews. It has just been through the years that the game has attracted this big following."

Its cultish appeal was capitalised on by LucasArts. When a Monkey Island: Special Edition remake was released in 2009, the nostalgia factor was enough for it to briefly top the sales chart.

Getting a book from on top of the rather considerable belly of a sleeping man represents a classic sequence in Monkey Island 2. Threepwood needs to get a similar-sized book and make the switch.

Nowadays point-and-click adventures rarely top the charts

It's a reference to the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark where Indiana Jones has to switch a bag of sand for the golden idol on a booby-trapped podium. He empties a handful of sand to get the weight right. Threepwood does the same by ripping pages out of the book.

In the same game, when Guybrush walks into his love interest's house, he is met with this line - "Of all the parties in all the houses on all the islands in the Caribbean he had to crash mine!"

The nod to Casablanca is obvious. Nods to Blues Brothers, the Princess Bride and even Bugs Bunny are not. There are also references to The Godfather, James Bond, Monty Python and, of course, Star Wars.

What these adventure games - which in many ways inherited the legacy of Infocom's text-based adventures - started was a new direction in storytelling in computer games.

"If any type of game is going to bridge the gap between games and storytelling, it is most likely going to be adventure games," Gilbert wrote, external.

"They will become less puzzle solving and more storytelling, it is the blueprint the future will be made from."

The storytelling elements provoke many of the fondest memories.

The only way to win sword fights was to be better at insults than your opponents

"You look at the 1990s and I don't think there's any other studio in history that's created such a broad range of brilliant games," says John Walker, an editor at gaming site Rock, Paper, Shotgun.

"Partly, it is being told a great story,"

"Gaming usually does a pretty dreadful job of it. A great story sticks with you in a way that sliding down lots of mountainsides doesn't. Shooting down a helicopter is hard to remember when you've done it in every game for the last decade.

"They captured a moment and were full of enough one liners and great gags. It's something that games struggle to do. Back then, the dialogue sunk into the public consciousness."