To whom does Wounded Knee belong?

- Published

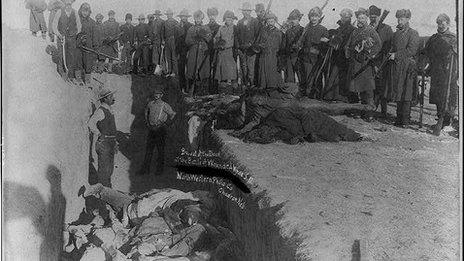

The burial ground at Wounded Knee: part of the massacre site is up for sale, with an asking price of $3.9m

Part of the historical site at Wounded Knee is up for sale. Should it be developed as a landmark or left in peace out of respect for the Sioux people who died there?

Almost as soon as the 1890 massacre at Wounded Knee was over, the battle to define what happened on that bleak December day began.

For decades afterwards, the official line from Washington was that the actions of the 7th Cavalrymen were heroic.

The White House and its allies in South Dakota had invested much political capital in seizing tribal land for US use, and using the army to quell Native American resistance.

What happened at Wounded Knee was promoted as a definitive end to these so-called "Indian wars", a final victory for the US government.

The administration of President Benjamin Harrison praised the military tactics used by the 7th Cavalry and awarded 20 of the soldiers Medals of Honor.

The New York Times told a different story, writing contemporaneously that the Native Americans had been "robbed when at peace, starved and angered into war, and then hunted down by the government."

At Wounded Knee, as many as 300 unarmed men, women and children were killed. And official reports from some in government criticising the massacre were simply buried.

For the Sioux descendants still living in the Pine Ridge reservation, who remember first-hand accounts of the atrocity, the news that a key part of that painful history could be sold outside the tribe has come as a shock.

A 40-acre parcel of land that's part of the massacre site is up for sale, and its owner has given the tribe until 1 May to come up with the $3.9m (£2.5m) asking price.

If they don't, land owner James Czywczynski says he will be forced to accept one of several offers he has already secured from commercial buyers, who may attempt to capitalize on the land as a tourist attraction.

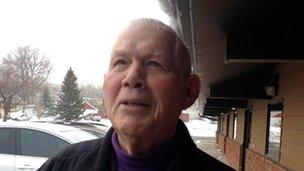

Joseph Brings Plenty says the land should belong to the Sioux

Many Lakota Sioux say it is a greedy act of blackmail, for land that is worth less than $10,000 on the open market.

The owner claims he was told by a government expert to start with a price of $100,000 per acre, based on the land's historic significance.

Mr Czywczynski, who has held the deed since the late 1960s, says he is exasperated that the tribe hasn't taken him up on earlier offers to sell, saying they've been indecisive for years. Now he's ready to move on.

"They want me to give them the land. Some say I should sell it reasonable," he says, speaking near his home in Rapid City.

"We're going to take the money, and distribute it to the family. Pay off some debts."

Standing on the desolate, snow-covered hilltop where the victims of the event are buried in a mass grave, tribe member Nathan Blindman says he could "still feel the anxiety" of his ancestors.

He, like most other living relatives of massacre victims, believe that developing the land in any way is simply wrong.

Burying the dead at a mass grave in Wounded Knee

But you only have to be on the Pine Ridge reservation for a short time to realize there is passionate disagreement over the issue.

Brandon Ecoffey, managing editor of the Native Sun News and a member of the tribe, speaks for some in the younger generation, who think rigid sentimentality is a mistake.

The burial site today

He believes that the Oglala-Sioux tribe at Pine Ridge needs to grasp the opportunity to buy the land and then generate income by creating responsible tourism at Wounded Knee. Currently, there is no official memorial at the site.

A memorial or museum would draw people to the area and generate jobs. If the tribe don't have the money to buy the land, they should accept help from outside sources to do so, he says.

"There are a number of memorial sites across the world, where people have created museums…that do justice to the people who died there," he said.

"Not profiting from our history does a disservice to both our community and our ancestors, who I feel would like to see us a little better off than we are right now."

Land owner James Czywczynski says he has tried to negotiate in good faith with the Sioux-Lakota

But it is not only the tragic killings of 1890 that give the land in this impoverished corner of South Dakota, which used to make up one tiny part of the Great Sioux Nation, historic significance.

In 1973, several hundred locals, together with radical activists from the American Indian Movement (AIM), external, poured into the nearby village of Wounded Knee to protest government abuse.

The protest resulted in a violent stand-off with federal agents that went on for 71 days.

The siege galvanized Native Americans throughout the continent, but left deep rifts locally, even within families, and led to murderous retribution on both sides.

At his headquarters in Minneapolis, one of AIM's founders, Clyde Bellecourt, a non-Lakota, says practical concerns should take precedent.

US troops at the battle of Wounded Knee

With often squalid-housing conditions, and outsized addiction and suicide rates, he argues, how can tribal government think about wasting resources on a piece of land, regardless of its history?

Many locals wonder why the land doesn't belong to the tribe already - a view echoed in a recent New York Times opinion piece , externalby the youngest leader among the Sioux family in recent memory, Joseph Brings Plenty.

The former chairman of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe believes that President Barack Obama could use an executive order to make the site a national monument.

Former construction worker Leon Grass is one of the elders who lives closest to Wounded Knee Creek. He's trying to press the claim of both of his grandmothers, who decades ago were deeded part of the land parcel in question.

He is not optimistic when asked when the pain echoing forward from the 19th Century would finally pass for this deeply wounded people.

"It's going to take some time. It's going to be passed down, from one generation, to another," he says.

But with time ticking down until the sale, it remains unclear whether the land will be passed down as well.