Mystery of 200-year-old British soldier found in the dunes of Holland

- Published

A preserved Coldstream Guards button and soldiers in modern ceremonial dress and the skeletal remains of the unknown soldier with a decomposed button found at the site

The 200-year-old body of a British Coldstream Guards soldier was found in sand dunes in the Netherlands. Who was he?

For more than two centuries, the remains of a soldier lay undisturbed on a windy beach in the northern Netherlands.

But in March 2011, birdwatchers discovered bones and metal artefacts among sand-dunes that had once been covered in asphalt.

The find was near an area known as the "Bonehole" because of the number of historic remains that had previously been unearthed.

A team of archaeologists was called in to dig further. Among them was 28-year-old Esther Poulus, whose involvement was to lead her to the National Archives in Kew, Surrey, in an attempt to discover the identity of the fallen soldier.

"We were taken to the site by the person who made the find, and it was quite hard to see," she recalls. "You could only see it if you were really close, and even then it was only the larger bones from the legs that were visible. The bones were very degraded and mixed with the ground."

She and her colleagues had to sift carefully through the sand using a brush and trowel, piecing together the remains of the body. They were working against the clock, as they had only been given two days on the site because a rare bird was about to start nesting, and the local government were keen for it not to be disturbed.

They had suspected that the body might be that of a soldier, given the area's association with a particular 18th Century battle. But the nationality of the soldier might have remained a mystery if it had not been for clues that had been left behind - muskets and tell-tale items of clothing.

In August 1799, Britain and Russia launched an invasion of northern Holland in an effort to topple the Batavian Republic and restore the House of Orange. The action formed part of the wars against revolutionary France, which supported the Dutch republic.

The British-Russian armies - including the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards, consisting of some 1,000 soldiers - arrived in Groote Keeten under the Duke of York. About 12,000 British soldiers were landed in total.

"It was a really special dig, as we knew instantly this was a period that wasn't very well known," Poulus recalls. "In the Netherlands, they call it the forgotten war - it didn't take very long, and was quite local."

The soldier was buried in his uniform, along with several muskets, which may simply have been thrown in the grave to dispose of them, or may have been fashioned into some kind of makeshift stretcher to carry his body to its resting place.

"When we found the buttons he had worn on his tunic, we thought, 'Wow - we can identify this soldier.'"

The team from Hollandia Archeologen brought in Cor Prins, an archaeological conservationist with a particular interest in the area's military history, to study the fragile pewter buttons.

He identified them as belonging to a member of the Coldstream Guards from the regiment's distinctive star and cross, which was barely visible on one of them. He was also able to make out the words "COVEN GARDEN", indicating that it had been made by a button-maker based in London's Covent Garden.

The brevity of the campaign - the British army had only been in the area for a day - helped the team date the soldier's remains. His torso had crumbled, and - crucially - he didn't have a head, which means that it may never be clear what killed him.

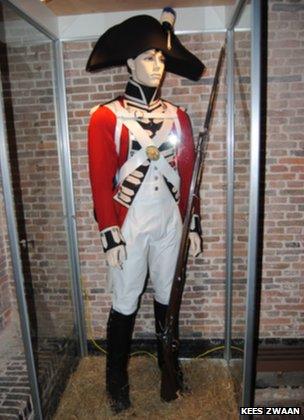

A museum in Northern Holland has constructed a life-sized replica of a Coldstream Guard from the era

After excavating the remains, Esther took up what became a personal quest to see whether the soldier could be identified, and - if possible - brought home. She has been partially successful, getting in touch with Coldstream Guards veterans via their website, and arousing interest from the regiment in the soldier's repatriation.

The Ministry of Defence in the UK does not deal with the repatriation of such historic remains, while the Commonwealth War Graves commission does not handle pre-1914 remains. So it was up to the regiment itself to engage with the Dutch authorities to decide what to do.

In the meantime, the unknown soldier's remains were stored at the local government depot for archaeological finds in northern Holland. But finally, on 2 May they will be handed over in Haarlem, in a child-sized wooden coffin to the British ambassador and representatives of the Coldstream Guards. A regimental musician is due to play the Last Post before Captain Oliver Morley brings the remains back home to the Regimental HQ.

Poulus's tenacity may have succeeded in narrowing down the identity of the soldier a little.

"The state of the bones meant we could not have done DNA testing, as they were too degraded, and usually you would use teeth for DNA. We have nothing to compare it with," she says.

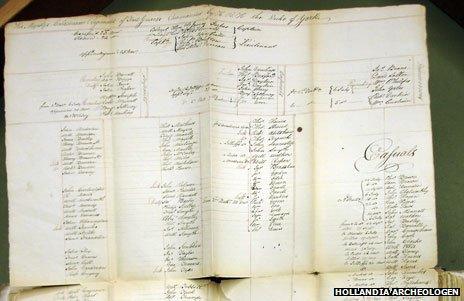

Poulus says that her research in the National Archives at Kew yielded six possible names, with Nathaniel Haines and Thomas Taylor the two most likely.

"The archives in the UK show that the two soldiers I think it could be were in the most dangerous jobs, as grenadiers. Judging by his remains, our soldier was probably around 1.80m tall, which was tall for the time. And the grenadiers recruited the tallest. So it's just a hunch, and a feeling I got when I saw the names."

So far, though, no way has been found to narrow this down, and the Coldstream Guards are not optimistic.

"Both are quite common surnames, and between 1790 and 1801 we had 12 Thomas Taylors who were serving in the Coldstream Guards," says retired Colonel Simon Vandeleur, the regimental adjutant who has been key in organising the repatriation. "The archaeologist's report is very good, but I don't think we can absolutely pin it down to two possibilities."

Skeletal remains discovered at the site in March 2011 were found alongside other material, including uniform, bullets and muskets

Two musket locks - the mechanisms used to fire the guns - photographed before and after restoration

Marks on the musket are probably makers' marks, according to the report. The broad arrow indicates that the musket is property of the British government

Archaeologists used assembly marks to identify parts of the same weapon

A muster roll from 25 June - 24 December 1799 mentions two soldiers, Nathaniel Haines and Thomas Taylor, who were killed on 27 August

"The regimental archives show well over 100 people killed in 1799 in the Coldstream Guards, and unfortunately some of the archives were damaged in the Blitz. At the time, they didn't look after those records very well - if a soldier died they destroyed his record, as they no longer needed to pay a pension, though we have got the archivist looking through the 1799 box," he says.

If the regiment can pinpoint a name, it will try to find the soldier's descendants, though Vandeleur admits it seems unlikely.

"But we will try. If not, Plan B is to cremate the remains, and scatter his ashes on Horse Guards Parade before the Trooping the Colour with due dignity and ceremony, and the guardsmen of Number 7 Company Coldstream Guards - his descendants - can tramp his ashes into the welts of their boots on one of the nation's most famous parade grounds, 200 years later. I hope it will be a fitting resting place for an unknown soldier who died long ago, doing his duty."

Poulus's archaeological report on the find opens with a quotation from Rupert Brooke's The Soldier:

"If I should die, think only this of me

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England."

Soon, though, this one soldier will come home at last.