MMR: How parents feel now about avoiding jabs

- Published

Huge numbers of children aged 10-15 were never vaccinated with the MMR vaccine, the result of a scare that caused panic among parents. The vaccination turned out to be safe, so how do those parents feel today about the decision they made?

"MMR Killed My Daughter", "New MMR link found to autism", "MMR fears gain support", "Why I wouldn't give my baby the MMR jab".

Ten to 15 years ago, barely a day went by without a newspaper story about the MMR - the combined vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella.

The media furore - started by a controversial paper published in the Lancet in 1998 which raised fears about a link with autism (which has since been comprehensively discredited) - led to panic among parents.

Measles can lead to pneumonia, seizures, inflammation of the brain and even death.

Most parents still went ahead with the MMR, but for some, the coverage led to confusion over whether they should give their child the vaccine that was recommended by doctors and the government.

"It was a frightening and upsetting decision - when you have a child, your instinct is to protect them from anything that could harm them, but I didn't know what to do," says Nicola Hamann, a 40-year-old office manager from Dorking, Surrey, who faced the daunting decision 13 years ago.

She says she delayed the first dose by four months, but when it came to the booster, she "couldn't go through with it".

Nicola Hamann says the decision over whether to give her son the MMR jab was a "constant worry"

The decision has played on her mind ever since, but it wasn't until last year that she had to reconsider.

"My son, then aged 14, was having other boosters. He came to the conclusion - with a tearful mother beside him - to have the MMR too.

"With the recent measles outbreak, I am relieved that he is now protected. But if it happened again I'd make the same choices," she says.

Even though the flawed nature of the science, and the flawed reporting of it, has been widely publicised - with the Cochrane Collaboration mega-review, external bringing together evidence from 54 different scientific studies in 2012 - there is still a shadow of scepticism in the minds of some parents.

But for Craig Thomas, a 36-year-old father of three from Morriston, Swansea, rejecting the jab is something he regrets. His 15-year-old daughter Chloe, and sons, Jordan, 14, and Kieron, nine, have all had measles in the recent epidemic.

"It's been devastating and I feel terrible guilt. My daughter lost half a stone in weight. My son's face was swollen, he had unbelievable spots and a rash. They were pretty much bedridden for three weeks.

"Years ago we were reading what was in the media, parents saying 'Don't have it done', basically. We never thought they would get measles and if I could turn back the clocks, I would," he says.

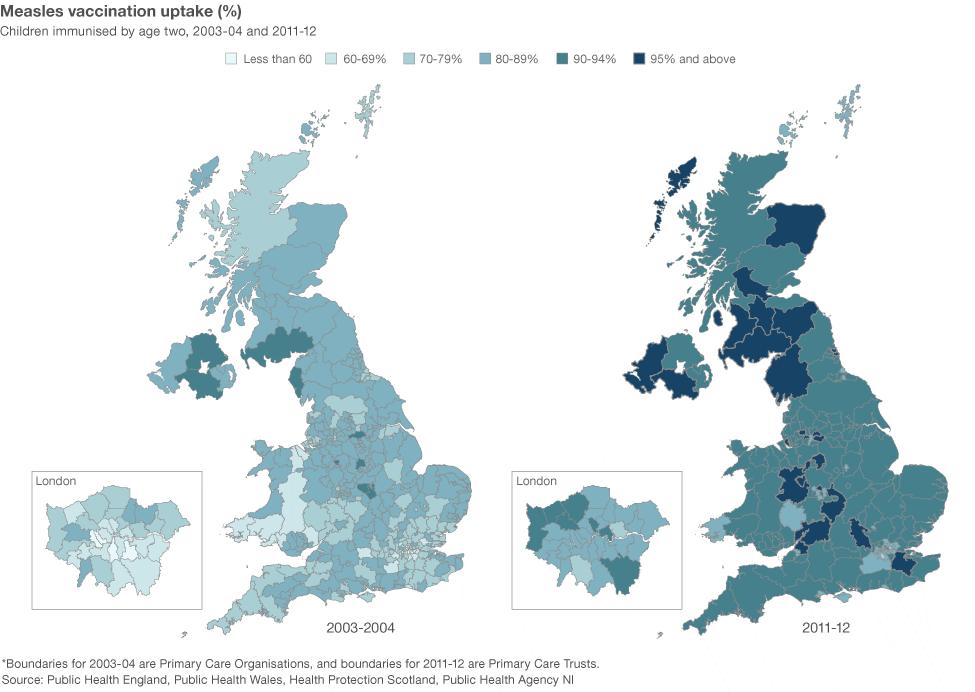

At its lowest rate, in 2003/4, fewer than eight in ten children were vaccinated - while in some areas in the UK less than half of children received the jab.

Now experts believe there are more than one million schoolchildren in England alone who are not protected against the disease and the government has launched a £20m catch-up campaign in light of the Swansea measles epidemic, which has seen more than 1,000 cases.

Dr Sarah Jarvis, a GP and regular on the BBC's The One Show, says at the height of the MMR scare, she would be having "half hour discussions with terrified parents" in her baby clinic on a daily basis.

"People needed a degree in critical reading to understand some of the science, but the newspapers were tapping into a public terror.

"The public wasn't getting a balanced view from the media, as it wasn't reporting the some of the robust studies in 1999 and 2000 which showed there was no causal link between MMR and autism," she says.

The volume of MMR coverage was also "huge", with 1,257 stories in the national press in 2002, according to science writer Dr Ben Goldacre. The story was also "covered extremely badly, and largely by amateurs," he argues, external.

Last month, Dr Andy Williams, of Cardiff University, said the UK media was guilty of "catastrophic failure" over its coverage. But the former editor of South Wales Evening Post said "[the readers'] concerns were totally genuine" and the paper never told parents not to get the jab.

Then there was the refusal of the prime minister of the time, Tony Blair, to state whether his son Leo had received the triple vaccine - on the grounds that this would invade their child's right to privacy - which added to the controversy.

In 2003, a paper by the Economic and Social Research Council found that, in the period between January and September 2002, 32% of all the stories about the MMR scare mentioned Leo Blair. Andrew Wakefield, the author of the controversial paper, was only mentioned in 25%.

For some parents, the lack of choice was a significant factor. They had fears - albeit unfounded - about the combined vaccine and wanted the option of three single vaccines on the NHS.

Gareth Payne, a 35-year-old driving instructor from Newport, says he spent £1,000 on jabs for his son, now 12, and twin daughters, now nine.

"At the time of our decision, our nephew had had the MMR and had become autistic. As a family we had reasonable doubt not to have the MMR.

"But when I went to the GP and asked about single vaccines, he told me his child had had the triple vaccine and that he was fine. I was shocked at his response - we have free choice in this country and parents should be able to decide how their children are protected," he says.

It's a sentiment that Sarah, from Essex, shares. Five years ago, she paid for her daughter to get single jabs after "doing a lot of digging".

"In my own experience, I feel that there is a lot of scaremongering about not having the MMR. I was treated with contempt and made to feel like an idiot, but I wasn't prepared to play Russian roulette with my child.

"I would have been more than happy to pay money into the NHS rather than going privately," she says.

The NHS says there is no evidence to support the use of single vaccines, external or to suggest that they are safer than MMR. It says single vaccines put children at risk of catching one of the diseases in the time between the jabs, and no country in the world recommends MMR and then offers parents a choice of having single vaccines instead.

There is also evidence that the more vaccines there are, the less likely everyone is to have them, which lowers the herd immunity, according to Jarvis.

There will always be some parents that don't like the idea of vaccinations at all.

The Guardian's Sophie Heawood wrote that she used to be "one of those people", external because the "NHS schedule of inoculations felt so over the top, full of diseases I'd last heard mention of in gloomy Victorian novels".

Goldacre says vaccine scares have been a recurring theme for three centuries, ever since vaccination was invented. In the 1990s, France was in the grip of a scare that hepatitis B vaccine caused multiple sclerosis, and there were concerns about side effects of the whooping cough vaccine in the 1970s in the UK.

But for Jarvis, there's little doubt, external that apart from clean water supplies, effective nationwide immunisation programmes have done more to increase the likelihood of living to adulthood than any other health measure in the last 100 years.

She says the MMR jab should never have created such a storm.

Parents standing in snaking queues outside emergency immunisation clinics this week may well be wanting answers about how it did.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external