Rebelling against Quebec's 'language police'

- Published

Residents of Quebec are battling over language that can be used on signs and in public spaces

The Canadian province of Quebec has seen a resurgence of its bitter language wars since Francophone nationalists returned to power last year. Now, some English speakers are rebelling against the "language police", reports Lorraine Mallinder.

Quebec's ruling Parti Quebecois is pushing a new law through the provincial parliament that would further reduce the use of English in schools, hospitals and shops.

As a result, many Anglophones fear they are being squeezed into insignificance.

For Harry Schick, owner of a pastry shop in Pointe Claire, an English-speaking municipality west of Montreal, it is nothing new.

His shop window, emblazoned with signs in 35 different languages, has attracted visits from what critics deride as the province's language police.

Inspectors from L'Office quebecois de la langue francaise - the Quebec French language office - say the lettering of French signs should be three times bigger than that of other languages.

But Schick, who has been taken to court and fined in the past, refuses to back down.

"Is a Francophone customer three times bigger than an Anglophone customer?" he asks.

"They deserve equal rights and equal billing. I want to take care of my customers in whatever language I can."

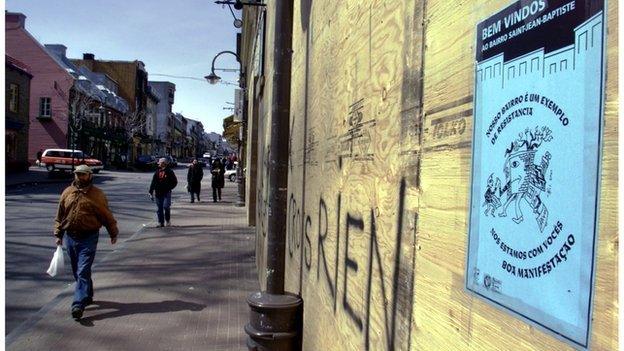

Expressions of Francophone pride are common throughout Quebec

Last week, he again sent inspectors packing - and they promised to return.

Schick's case is the latest in a series of confrontations that have set social networks and talk radio shows abuzz.

In the so-called "pastagate" scandal, language inspectors attempted to strike the word "pasta" from the menu of a Montreal Italian restaurant.

And in October, Montrealers were appalled by a man's report that a French-speaking paramedic, external had refused to speak English to him while treating his convulsing toddler.

The public transport system has also been the scene of altercations between French-speaking staff and English-speaking passengers.

Bilingual signs can be seen across the province and beyond

Tensions are running high in a province that seemed to have struck a linguistic peace of sorts since the heady days of Quebec nationalism, periods marked by two failed referenda on independence in 1980 and 1995.

In the late 1970s, the first Parti Quebecois government passed Bill 101, a law establishing French as the main language of Quebec. The law mandated the use of French in the workplace and required immigrants from outside the province to attend Francophone schools.

The proposed new law would further bolster French.

Among other measures, it would deny official bilingual status to some municipalities and restrict entry to English-speaking post-secondary colleges.

Students who speak French, for example, would automatically be placed at the back of the admissions queue, a move Quebec nationalists say would protect English-speaking students. Critics, however, say this would marginalise English-speaking colleges.

Quebec minister Jean-Francois Lisee of the Parti Quebecois is tasked with building bridges to the province's embattled Anglophone population.

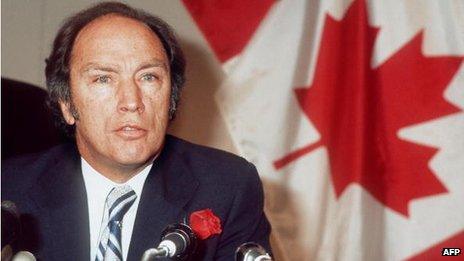

The Parti Quebecois introduced the 1970s-era bill making French the province's official language

He acknowledges that the "tough" measures will have to be toned down to win cross-party support.

His party leads a minority government but is counting on the support of the Coalition Avenir Quebec, itself led by a former nationalist.

The new language bill is necessary in a country where the French language is under threat, he says.

He believes that Canadian bilingualism, which became official federal policy in the late 1960s under the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau, is not working.

According to Lisee, 50% of every new generation of French speakers from British Columbia to Ontario adopt English as a mother tongue.

But Quebec's language laws have stemmed the Anglophone tide, he says.

Today, he says, 85% of children of immigrants to the province are schooled in French.

But a number of elite institutions on both sides of the linguistic divide, including the Quebec Bar Association, the Human Rights Commission and the province's 48 post-secondary colleges, have come out against the proposed law, warning the changes will trample on individual rights.

"This isn't about taking sides," says Pearl Eliadis, a human rights lawyer who has testified on behalf of the bar association.

"It's misleading to say that French is the founding culture of Quebec - Quebec has at its root two European founding peoples."

The English, she says, were not far behind the French.

"At the end of the day, this is about harnessing nationalism," she says.

For Lisee, Quebec's independence is only a matter of time.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau oversaw the institution of a national policy of French-English bilingualism

"The relationship between Canada and Quebec is like the last stages of a couple that will divorce at some point," says Lisee.

"There's no love, there's no hate, there's not even any resentment. There's simply nothing there."

He is, however, at pains to point out his apparent indifference doesn't extend to Quebec's Anglophones.

"They are welcome to stay," he says. "This is also their home."

The sentiment may not be reciprocated. A February survey, external found that 42% of the province's English speakers are considering leaving the province.

Schick, who has received support from Francophone and Anglophone customers alike, is among them.

"Quebec is my home as long as it doesn't separate from Canada," he says. "There comes a point where you have to say, 'That's enough.'"

Lorraine Mallinder is a freelance journalist based in Montreal. She is a regular contributor to the BBC World Service, Radio Canada and The Irish Times.

- Published5 September 2012

- Published16 October 2010