Self-portraits and social media: The rise of the 'selfie'

- Published

Celebrity selfies: Kelly Brook, Justin Bieber and Rihanna

There's a mania for sharing self-taken photographs online. But why, asks Charissa Coulthard.

The first smartphone with a forward-facing camera was the watershed moment.

You only need this second, forward-facing camera if you want to take pictures of yourself. Could there be any more conclusive indication of the ubiquity of the self-portrait or "selfie"?

The cameras, which focus automatically from arm's length, invite us to photograph on the spur of the moment, regardless of location or company.

Images can be shared with thousands of other people. Its immediacy - Look where I am! Look what I'm doing! Look at what I look like! - is exciting. To some.

There's the high angle photo, awkwardly featuring the taker's arm. There's the mirror self-portrait. There are posed selfies, with Bambi-eyes and pouting lips. And there are group selfies, even dodging a stranger's kind offer to take the same photo.

A search on photo sharing app Instagram retrieves over 23 million photos uploaded with the hashtag #selfie, and a whopping 51 million with the hashtag #me.

Evolution of a selfie: Charissa Coulthard before and after tips, and experimenting with a new look

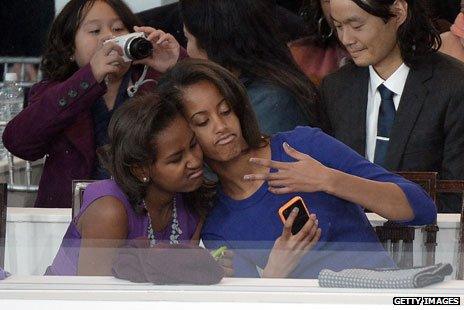

Rihanna, Justin Bieber, Lady Gaga and Madonna are all serial uploaders of selfies. Model Kelly Brook took so many she ended up "banning" herself. The Obama children were spotted posing into their mobile phones at their father's second inauguration. Even astronaut Steve Robinson took a photo of himself during his repair of the Space Shuttle Discovery.

Selfie-ism is everywhere. The word "selfie" has been bandied about so much in the past six months it's currently being monitored for inclusion in the Oxford Dictionary Online.

The first self-portrait photograph is thought to have been taken by camera pioneer Robert Cornelius in 1839, but whether or not it's a true "selfie" is debatable.

"It's likely he may have had a friend or assistant to make the actual exposure," says Dr Michael Pritchard, historian and director general of the Royal Photographic Society.

"It's more likely the first 'selfies' were taken a bit later on. The first shutters with self-timers were available as early as the late 1880s, and allowed five or ten seconds for the subject to get into shot.

"Some cameras also had long cable releases, allowing the subject to press the shutter from a distance."

The first selfie in outer space?

Sharing of self-portraits also pre-dates the internet. The 1860s saw huge popularity for the sharing of cartes de visite - little photocards. Even the photo booth dates back as far as 1880, and attracted groups of friends much as it does today.

Then there was the Polaroid. First sold from 1948 but not truly "instant" until its 1970s heyday, Polaroid cameras could be held at arm's length and encouraged people to take more intimate photos.

"The Polaroid's big plus was that you didn't have to take a film to be developed", explains Dr Pritchard. "It freed up the amateur who didn't have a darkroom from having someone look at the photograph before he or she did."

Technological advances mean that where we once had to remain very still due to long exposure times - creating a more formal image - now we can be captured quickly and informally.

Some people prefer the images they take themselves.

"Mirror images are primarily private and transient," says Dr Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Centre in Boston. "We see ourselves alive and dynamic, a person in progress."

Emily Cook, a 22-year-old Instagram user from Lincoln, believes they elicit a feel-good factor. "It's always nice to document a good hair day, or an outfit you love. And generally, especially with Instagram, there's a real feel-good attitude towards selfies, and as vain as it may be, you know that if you're not feeling great, there's someone who will 'like' your photo and tell you you're pretty."

It is also, she believes, just another way to tell a story through social networking: "Instead of saying you're going to work, a photo of you in your uniform does that."

According to Dr Rutledge, we enjoy opportunities to experiment with different identities - and the selfie allows just that. "We all want to be able to 'try' on a new image and imagine how we would feel as that part of ourselves," she explains.

According to recent findings from the Pew Research Centre, teenagers in America are sharing more information than ever about themselves on social media. Of those studied, 91% post photos of themselves online - up from 79% in 2006.

One theory is that the "selfie" tells other people how we want to be seen.

Dr Aaron Balick, a psychotherapist who has written a book about the human motivations behind social networking, explains that we have both "active online identities" and "passive online identities".

The Obama girls take a selfie

"A passive one is like when you search for yourself, or when friends post information about you - it's your online identity that you have no control over," he explains. "Active online identities are ones you can control, like a Facebook profile.

"A selfie is an expression of an active online identity, something you have some control over. You might take lots, but you'll publish the ones you like - even if they are silly or unflattering."

The selfie trend as a whole has attracted a significant amount of criticism.

For many it's still inexorably associated with "sexting" - sending sexual photographs via text, which are typically self-taken. Sexting is a growing problem in schools.

Of course, most selfies are clothed and innocuous. But they can still get people in trouble.

"Just like with other forms of behaviour that push the edges of the social envelope, those who create provocative selfies to get attention will not only not get the kind of attention they really want, but may find that they have created something that they have a hard time getting rid of," says Rutledge.

Selfie-taker Emily points out that her generation has forever been warned about internet risks and, as a result, she's careful. "I know the circle of people who see my images, and if any of them make me uncomfortable - I have received dodgy messages - I just block them.

"At the end of the day it's my face and body, and if I choose to put it online that's up to me, but I also have to take the blame if they fall into the wrong hands. I'd never post anything I wouldn't want printed and sent to my mum."

Selfies are most commonly criticised not for their potential risks, but for their associations with vanity and narcissism. Isn't it a bit, well, cringeworthy to take the time to photograph ourselves, and assume our friends (not to mention potential strangers) will want to see the results?

"Culturally people aren't supposed to self-promote or 'brag' - especially women," says Rutledge. But attitudes depend on how we feel more generally about sharing personal information on the internet. The increase in sharing of all kinds of personal information and images may have redefined what is "normal".

There will always be critics, Rutledge predicts.

"Many view selfies as acts of self-focus and cries for attention."

How to take the perfect selfie

1. Let there be light: Photographer Mindy Stricke says lighting is the key: "Natural light is best. The 'magic hour' is the hour after sunrise and just before sunset, and will produce the most flattering sunlight." If natural light is missing, stand by a source of artificial light and make sure the flash is off.

2. Out of arm's way: "Having your arm reached out in shot is only going to be so flattering," says Stricke. She advises experimenting with a mini tripod for your smartphone, or downloading a free self-timer app.

3. Rule of thirds: "Try to think of how to compose in thirds, like eyes a third of the way up, head a third of the way into the picture - ideally from the top or side," says Bedford-based photographer Stuart Kearey. He advises ensuring a space between you and the background, to achieve a depth of image.

Wrong: Charissa faces the camera square-on, making for a boring composition, and the photo is over-lit

Right: Charissa is facing the camera at a slight angle, and has accessorised her portrait with a scarf

4. Your 'good' side: "Positioning the camera slightly above your eyeline tends to be the most flattering," says Stricke. She also advises angling your face or body to one side.

5. Be bold: You might feel silly, but trying out a new look or different hairdo can help you feel more confident. "Changing your look can help make you feel just a little different or more fancy in a photo, and this confidence will shine through your final images," says Emma Chapman of A Beautiful Mess. Kearey suggests adding a prop such as a hat, scarf or piece of jewellery.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external