10 of popular culture's best Machiavellian characters

- Published

It's 500 years since Niccolo Machiavelli wrote The Prince, his guide to statesmanship for a hypothetical leader. There have been an extraordinary range of characters in popular culture that we have come to call "Machiavellian".

(Spoiler alert: Multiple key plot details revealed below)

The word "Machiavellian" first and foremost describes a relationship to the works of the 16th Century Florentine theorist Niccolo Machiavelli.

But its more common usage relates to the qualities people have gleaned from Machiavelli's The Prince.

The Oxford English Dictionary says: "A person who practises expediency in preference to morality; an intriguer or schemer. Usually derogatory." The Merriam Webster Dictionary says "marked by cunning, duplicity, or bad faith".

Scholars have often been vexed by the crude popular interpretations of Machiavelli's work but his supposed ethos has taken on a glorious life of its own in the form of a slew of splendidly devious characters.

1. Tony Soprano - The Sopranos

James Gandolfini as Tony Soprano and Edie Falco as wife Carmela

The fictional boss of the Soprano crime family in northern New Jersey is a man happy to lie, throttle and shoot his way to the continued occupancy of his throne.

But the kingpin expresses dissatisfaction with The Prince and the way his Italian crime colleagues dwell on Machiavelli's work. Instead, he reads and espouses The Art of War by Chinese general and philosopher Sun Tzu, after it is recommended by his therapist.

"Now most of the guys I know read that Prince Matchabelli. And I had Carmela get the Cliff Notes once and it was OK, but this book [Sun Tzu's Art of War] is much better about strategy."

Yet even a casual reader of The Prince will see parallels with Tony Soprano's modus operandi.

Arguably the best known section of The Prince is that on whether it is better to be feared or loved.

"Upon this a question arises: whether it be better to be loved than feared or feared than loved?" writes Machiavelli. "It may be answered that one should wish to be both, but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, it is much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either must be dispensed with."

2. Francis Urquhart - House of Cards

Francis Urquhart (known by his initials FU), a fictional politician with unquenchable ambition created by Michael Dobbs, is without doubt an uber-Machiavellian, gifted in the dark political arts.

Portrayed by actor Ian Richardson in the 1990 television series House of Cards. Urquhart's quest for power, his utter ruthlessness and political dexterity make him a classic anti-hero, remembered for his catchphrase: "You might think that, I couldn't possibly comment."

The link to the Italian philosophy was made explicit by screenwriter Andrew Davies, external. In Urquhart's backstory he has taught Renaissance Italian history prior to politics and is an expert on the Medicis and Machiavelli.

Like The Prince, he is concerned with ends rather than means.

He is at once fiercely principled, wedded to authoritarian social policy and a strict economic doctrine. On the other hand he is utterly without morals in his pursuit of power.

Passed over for a cabinet position when his candidate for prime minister rises to power, Urquhart sets out to destroy everyone in his path as he spins a web of manipulation. He resorts to blackmail, treachery and murder.

3. Tom Ripley

Of the amoral protagonist of Patricia Highsmith's novels and Anthony Minghella's film The Talented Mr Ripley, philosopher John Gray says Tom Ripley is a "true Machiavellian".

"Ripley does not allow his behaviour to be governed by his emotions but wherever possible follows a path of careful deception worked out well in advance.

"He is ready to use violence to achieve his goals, but only when he calculates doing so is necessary and will be effective. He is detached from traditional morality and has a public mask which conceals his purposes and strategies.

"Where Ripley is the opposite of Machiavellian is in his goals.

"Machiavelli wanted ruthlessness to be used for political ends - achieving a self-governing republic - whereas Ripley is ruthless in order to achieve purely personal ends - an affluent, leisured life in beautiful surroundings.

"In effect, Ripley is Machiavelli for a privatised age."

4. Iago - Othello

While Tony Soprano, Francis Urquhart and Tom Ripley are all villains that readers/viewers struggle not to like, Othello's Iago is cut from a very different cloth.

"Iago is Shakespeare's best-known Machiavel, yet he doesn't ever admit Machiavelli's influence," writes Prof Gordon McMullan of the London Shakespeare Centre at King's College London.

Rory Kinnear as Iago (left), with Adrian Lester as Othello in the National Theatre's current production

"Unlike the Host of the Garter in Merry Wives - who asks, tongue-in-cheek, 'Am I politic? Am I subtle? Am I a Machiavel?' - Iago claims no influences, giving the impression that he has thought up his actions all by himself, and certainly, given the messy execution he is to undergo after the end of the play, he has failed to follow Machiavelli's advice to keep power at others' expense.

"But, then, English dramatic Machiavels usually fail - the original English 'stage-machiavel', Marlowe's Barabas in The Jew of Malta, ends up being boiled to death in front of the audience - and Iago is in any case not in a position to follow the Italian's advice simply because he doesn't have the status - he does not hold the kind of position of power to which Machiavelli addressed his advice.

"Iago's motivations are perverse, self-contradictory, and complicated enough to have defied the efforts of generations of critics to unpick them - does he do what he does because he wants a pay rise, because he thinks Othello has slept with his wife, because he is in love with Othello himself?

"TS Eliot noted that Machiavelli's influence has been "the history of the various ways in which he has been misunderstood" - that is, Machiavelli was describing what the rulers of Italian city-states did, or had to do, in order to stay in power, not advocating that these were things they should do without concern for the moral value of their actions. Misunderstood or not, Machiavelli has been an endless resource for English dramatists."

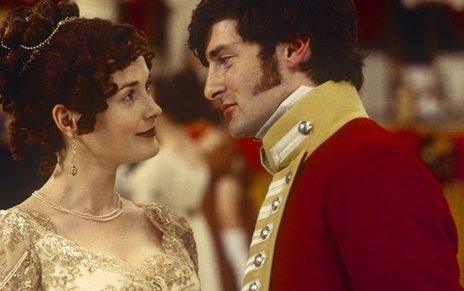

5. Becky Sharp - Vanity Fair

Natasha Little as Becky Sharp with another woman's husband

Ah, Miss Sharp, anti-heroine of William Thackeray's Vanity Fair. Sharp by name and sharp by nature, she deploys her wits and wiles to climb the social ladder by the only means available to a woman in Georgian England - strategic flirtation.

"Recollect that Miss Sharp had no kind parent to arrange these delicate matters for her, and that if she did not get a husband for herself, there was no one else in the whole wide world who would take the trouble off her hands," notes the narrator.

Petite and attractive, Sharp is also, as the narrator puts it, "a young person of no ordinary cleverness". She deploys this cleverness and those looks to considerable - but not always happy - effect.

For much of the book, her dislike of her son, little Rawdon, is palpable. But at a family Christmas gathering, on "seeing that [maternal] tenderness was the fashion", she calls him to her for a kiss. As Machiavelli says in The Prince, so long as one appears to act virtuously, most people will believe in one's virtue. Sharp's public display of affection is rather undone when her son turns red and loudly replies: "You never kiss me at home, Mamma."

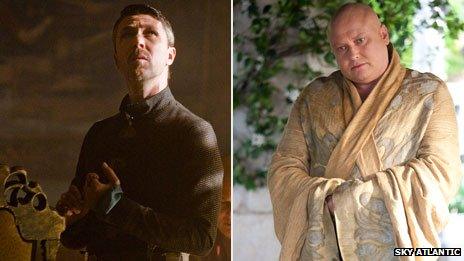

6. Lord Varys and Lord Baelish - Game of Thrones

Aiden Gillen as Lord Baelish (left) and Conleth Hill as Lord Varys

The battle between Lord Varys (aka The Spider) and Lord Petyr Baelish (aka Littlefinger) to out-Machiavelli each other is delicious for fans of Game of Thrones.

Varys is a eunuch in the finest traditions of Byzantine history, lacking both good birth and the possibility of advancement through a military career, he instead makes it his business to protect his wealth and his life by making sure he is always useful to those who might otherwise be tempted to destroy him.

As the king's spymaster, his nickname is derived from the web of informants he has assembled to gather the snippets of information he needs to manipulate other people into advancing his own interests.

Baelish is absolutely ruthless, and apparently more vindictive than Varys. When an assistant of his reveals information to Varys, he offers her to the sadistic king knowing she will be shot to death by crossbow bolts.

He is ambitious, wanting to gain the noble status he lacks. His main expertise is in finance, an echo of the Medici family who, over the course of a couple of generations, turned financial might into political control in northern Italy.

Apart from his control of palace finances, Littlefinger again deals in information which he uses to set faction against faction.

"Chaos isn't a pit. Chaos is a ladder," he suggests. "Many who try to climb it fail, and never get to try again. The fall breaks them. And some, given a chance to climb, they refuse. They cling to the realm, or the gods, or love. Illusions. Only the ladder is real. The climb is all there is."

7. Milton's Satan - Paradise Lost

"John Milton's Satan - the rebel, the charismatic, the evil and tragic hero - flows from the pen of a radical and sincere republican who had read and understood Machiavelli's works well," writes Filippo Del Lucchese, lecturer in politics and history at Brunel University.

"In Milton's earlier writings such as the Commonplace book, he had praised Machiavelli for his most radical positions, including his point that 'popular uprisings are the occasion for the recovery of liberty and therefore should not be condemned, for they generally arise out of just causes and complaints'.

"Machiavelli stressed that 'it is necessary, for a prince, to learn to be able not to be good, and to use this and not use it according to necessity' - through Milton, he found no less than a fallen angel to listen to him."

8. Marquise Isabelle de Merteuil - Les Liaisons Dangereuses

Intriguers and intrigued: Marquise de Merteuil, Vicomte de Valmont and Madame de Tourvel

The Marquise Isabelle de Merteuil, played by Glenn Close in Dangerous Liaisons, based on the 18th Century novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, is one half of a Machiavellian duo of 18th Century aristocrats (the other is John Malkovich's ruthless Vicomte de Valmont). Using sex as a weapon to conquer those around her, the marquise concocts a wicked plan to take revenge on a former lover by ruining the virtue of the young woman he is to marry.

She employs another former lover - Valmont - to do the dirty and seduce the young woman Cecile de Volanges. The marquise's world is one of intrigue, manipulation and deceit. Like Machiavelli's prince, the marquise is both repellent and charismatic.

An arch schemer, she will stop at nothing to destroy both men and women, as long as she remains in control. When Valmont admires the way she can get people to do whatever she wants, she explains how she invented herself in a way that she could survive in a world dominated by men.

"When I came out into society I was 15. I already knew that the role I was condemned to, namely to keep quiet and do what I was told, gave me the perfect opportunity to listen and observe. Not to what people told me, which naturally was of no interest, but to whatever it was they were trying to hide. I practised detachment. I learned how to look cheerful while under the table I stuck a fork into the back of my hand.

"I became a virtuoso of deceit. It wasn't pleasure I was after, it was knowledge. I consulted the strictest moralists to learn how to appear, philosophers to find out what to think, and novelists to see what I could get away with, and in the end, I distilled everything to one wonderfully simple principle - win or die."

In a world where, according to Machiavelli, so many people are inclined towards "evil", to win, rather than die, necessitates the adoption of amoral strategies. "How one ought to live is so far removed from how one lives that he who lets go of what is done for that which one ought to do sooner learns ruin than his own preservation," writes Machiavelli.

Machiavelli, however, might take issue with the marquise's unrelenting cruelty. Cruelty, Machiavelli wrote was a necessary evil to maintain order and justified in the interest of public good. The marquise, however, appears to revel in it for her own enjoyment.

9. Francis Walsingham in Elizabeth

Not the real Francis Walsingham, but the one played memorably by Geoffrey Rush in Shekhar Kapur's Elizabeth.

This film version is a slyly smiling murderer, equally happy dispatching a youth who gets in his way as a rival queen.

The real Walsingham has enjoyed a reputation as a talented "spymaster", controlling the informal espionage network that protected Elizabeth and England during a reign marked by seemingly endless intrigue.

He had little compunction about torturing Catholics for evidence of plot and conspiracy. But in the moral milieu of the time this was typical for a man in his position.

More than just expedient, Rush's Walsingham seems to relish the web-spinning, manoeuvring and engineering of downfalls.

10. Sonny LoSpecchio

Chazz Palminteri as Sonny LoSpecchio

Another Mafioso has to make the list. British philosopher Bertrand Russell called The Prince "a handbook for gangsters" and in Robert De Niro's 1993 film A Bronx Tale the book is prominent.

Ruthless crime boss Sonny LoSpecchio tells a teenager he has befriended that he read Machiavelli in prison and lives his life accordingly.

His concepts of leadership stem directly from The Prince. LoSpecchio explains the importance of "availability", external - keeping close to his territory. This way, he says, his allies will have "more reason to love" him, because they can count on his protection, while his enemies would have more reason to fear him and "will think twice because they know I'm close".

The teenager then asks: "Is it better to be loved or feared?", to which LoSpecchio responds: "That's a good question. It's nice to be both, but it's very difficult. But if I had my choice, I would rather be feared. Fear lasts longer than love."

"The trick," he goes on to say "is not being hated". It is almost as if The Prince, himself, were speaking - but there the similarities end. LoSpecchio ends up being assassinated - something a wiser prince might have managed to avoid.

Reporting by Kathryn Westcott, Finlo Rohrer and Megan Lane

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published17 May 2013